On this day in 1562 – 23 Protestant Huguenots were massacred by Catholics in Wassy, France, marking the start of the French Wars of Religion. One result was the eventual growth of the Linen industry in Ulster, which set the scene for the industrialisation of Belfast. My friend Professor Rene Frechet of the Sorbonne in Paris was a devout Huguenot, and to him I dedicate this day.

But it is also Saint David’s Day (Welsh: Dydd Gŵyl Dewi), the feast day of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, and falls on the 1st of March each year, the day having been chosen in remembrance of the death of Saint David for tradition holds that he died on that day in 589. The date was declared a national day of celebration within Wales in the 18th century.

St David (Welsh: Dewi Sant) was born towards the end of the fifth century. He was a scion of the British royal house of Ceredigion, and founded a Celtic monastic community at Glyn Rhosyn (The Vale of Roses) on the western headland of Pembrokeshire (Sir Benfro), at the spot where St David’s Cathedral stands today. David’s fame as a teacher and ascetic spread throughout the Celtic world. His foundation at Glyn Rhosin became an important Christian shrine, and the most important centre in Wales. The date of Dewi Sant’s death is recorded as 1 March, but the year is uncertain – possibly 588. As his tearful monks prepared for his death St David uttered these words: ‘Brothers be ye constant. The yoke which with single mind ye have taken, bear ye to the end; and whatsoever ye have seen with me and heard, keep and fulfil’.

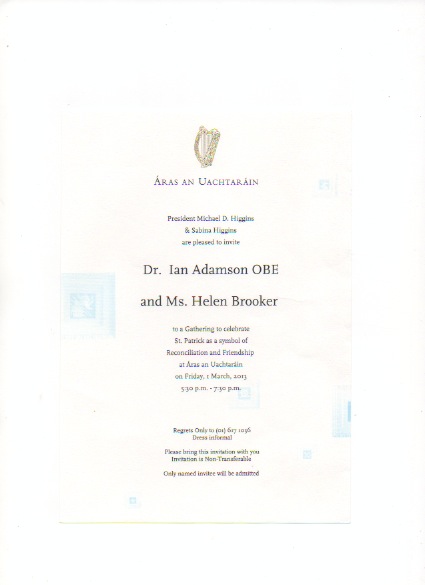

And today President Higgins invited our Ullans Academy to his Gathering at Aras an Uachtarain to celebrate St Patrick as a symbol of Peace and Friendship.

Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen:

Tá áthas orm féin agus ar Sabina fáilte a chuir róimh anseo tráthnóna. Is mór againn gur tháinig sibh, go mór mór na daoine a thaisteal ó Thuaisceart Éireann.

You are all most welcome to Áras an Uachtaráin – Sabina and I greatly appreciate your presence this evening.

A year ago, Sabina and I travelled to Ballynahinch in County Down to attend a dinner hosted by the Friends of the St. Patrick Centre in Downpatrick. The event was titled the “Spirit of St. Patrick” and what an inclusive and generous spirit it proved to be. What impressed me most about that evening was the ease with which senior political representatives of both major traditions on this island were very happy to come together in the name of St. Patrick. It was very clear to me that the narrative of Patrick, the values that he represented and the impact of his legacy were widely shared among all communities in Ireland.

The story of Patrick’s life provides a common ground from which all traditions draw inspiration. It was only in recent times however that it has become our practice to come together on this island to celebrate the shared heritage of Patrick.

For the best part of two decades political representatives from both parts of the island have travelled to the United States to participate in St. Patrick’s Day celebrations. Indeed, these occasions may even have provided the first opportunities for political representatives of both traditions to meet each other in the perceived safe space of Washington or New York.

These were crucial moments in the peace process and that engagement around St. Patrick’s Day in the United States has yielded, and continues to yield, important political and economic dividends for the entire island. But perhaps it is time to complement that overseas engagement with a greater emphasis on a coming together in Ireland to celebrate, explore and reflect on our shared Patrician heritage.

Building on the good work of the St. Patrick’s Centre in Downpatrick and indeed other Patrician centres, I was anxious to host a gathering that would bring together representatives of organisations who are active in promoting cross-community and North/South contact and cooperation, as well as people who come from locations that are linked with the life and legacy of St. Patrick. So while this evening’s gathering may be somewhat of an eclectic congregation, there is at least one thing we all share – a huge respect for St. Patrick as the symbol of peace and friendship on this island.

As an academic and politician, I have always been deeply interested in migration. I have been particularly fascinated by the paradox of the migrant being both marginalised and vulnerable and yet, over time, developing the capacity to become a major agent of change in his or her adopted homeland. Neither the Scots-Irish nor post-Famine Irish emigrants had an easy time of it on arrival in the United States; indeed the hardships they endured were severe. Yet, they had the resilience and ingenuity to not only overcome these obstacles but actually transform their host society.

In his life, Patrick embodied this paradox. He was the ultimate involuntary migrant. His life as an immigrant slave in Ireland was lived in misery and hardship; cut off from his family and banished to mind sheep on Slemish. Despite this marginalisation and powerlessness, Patrick in all his human vulnerability still found the courage, the faith and the strength to become the catalyst for the spiritual transformation of Ireland.

In his Confessio, he says: “I am the sinner Patrick. I am the most unsophisticated of people, the least of Christians”. He was an ordinary and very vulnerable man who had the generous vision and the resources within himself to transform this island. At a time of great economic challenge, we should remember that Patrick refused to be defined by his apparent weakness and vulnerability. On the contrary, he actually used them as powerful agents of change to achieve his vision of a Christian Ireland.

The other quality that strikes me most forcibly from Patrick’s life was his decision to forgive. This was not a casual forgiveness or an expedient amnesia. Patrick was the victim of a huge injustice; a terrible hurt was inflicted upon him by people who regarded his life as of little value. After years of suffering misery at their hands, he managed to escape to return to his family in Britain. In what can only be regarded as a completely counter-intuitive move, Patrick then decided to return to Ireland to minister to the community that had enslaved him.

From our historical experience in this island, we are sadly familiar with the phenomenon and consequences of the negative spiral of hatred and hurt. As Séamus Heaney wrote: “Human beings suffer. They torture one another. They get hurt and they get hard”.

Patrick had been hurt but he refused to get hard. He did the opposite; he devoted his life to addressing the needs of those who had hurt him and, through conscious acts of generosity and forgiveness, set about dismantling the infrastructure of hate of which he had been a victim. In the words and prayers ascribed to him, Patrick also showed a great respect for symmetry with nature and the power of blessing.

Thankfully, in recent years many people on this island have emulated the vision, generosity and forgiveness of Patrick. I commend all the people in leadership positions – at community and political level – who have made the conscious and strategic decision not to get hard but to tackle the mountain of accumulated hurt by acts of courage and generosity towards the other community. These decisions were made not because they were easy, but because they were right and because they represented the only pathway out of the cul-de-sac of injustice and violence that offered only embedded misery to every community in Northern Ireland.

The life and legacy of St. Patrick has, therefore, a lot to teach us and it is a matter of great celebration that all communities on this island can now come together in the name of our shared Patron.

Like St. Patrick, our flags – the Union Jack and the Tricolour – also represent a noble aspiration. The Tricolour signifies the peaceful coexistence of the Gaelic and Orange traditions while the Union Jack brings together the cross of St. Patrick with that of St. George and

St. Andrew. How sadly ironic then that the flags which reflect this positive aspiration should in recent months have become a source of division and contention in certain communities.

The achievement of peace and inclusive politics over recent years has given us the space to examine and explore our respective identities in all their complexity – celebrating what we share in common (such as St. Patrick and our wonderful music and heritage) and, where we differ, to at least respect the perspective of the other. Those positive threads of commitment to a discourse that, not only tolerates difference, but is able to place oneself in the narrative of the other, including the opinions of opposites, are most valuable threads on the loom of democracy.

I believe in politics. I have devoted much of my life to its practice.

I know that, at its best, politics is a creative and healing art. We need that healing now. I hope that over the coming weeks and months, we will see politics at its best; deployed constructively and collectively towards the achievement of a shared society in Northern Ireland, one where difference is a source of strength rather than division.

On a lighter note, one thing all traditions on this island share is our love of culture – of music, dance, literature, theatre and art. The season of St. Patrick is a time when it is very apt to celebrate that culture in all its richness and diversity and to show-case its excellence to the world. I have said on many occasions that while the experience of the so called Celtic Tiger failed to live up to the best versions of Irishness, we have not been failed by our artists. In fact, the artists that come from both parts of our island are a huge moral resource and great reputational asset for Ireland.

In recent days, I have invited to Áras an Uachtaráin some of Ireland’s best artists to demonstrate through conversation and performance the depth and breadth of our island’s cultural richness and its reach across the global diaspora. Titled “The Glaoch” or Calling, the fruits of that endeavour will be broadcast and available world-wide over the St. Patrick’s Day week-end. I hope it makes a contribution to our celebration of Irishness and that it demonstrates why there are very good reasons to be proud of our island in all its diversity.

The artists we have invited this evening – The West Ocean String Quartet – reflect that diversity. They hail from three provinces across Ireland; only the Pale is unrepresented. The Quartet operates in the interface between traditional and classical music and their programme this evening reflects both Irish and Scottish influences.

Ba mhaith liom buíochas a ghabháil leis an West Ocean String Quartet as ucht seinm dúinn, agus libhse ar fad as ucht a bheith linn tráthnóna. Is mór agam sibh a bheith i láthair in onóir ár nÉarlamh Naofa, agus i mbaol a bheith roimh am, guím beannachtaí na Féile Pádraig oraibh.

Go raibh mile maith agaibh go léir – thank you very much.