Last wreck remaining of a power and order overthrown,

Much needing solace;

And, ah me!, not in the empty lore

Of bard or druid does my soul find peace or comfort more;

Nor in the bells or crooked staves nor sacrificial shows

Find I help my soul desires,

Or in the chants of those

Who claim our druids’ vacant place.

Alone and faint, I crave,

Oh, God, one ray of heavenly light to help me to the grave,

Such even as thou, dead Congal, hadst;

That so these eyes of mine

May look their last on earth and heaven with calmness such as thine.”

Set as Ulster is at the North Eastern corner of Ireland, facing Britain across a narrow sea and separated from the rest of Ireland by a zone of little hills known as Drumlins, marshland, lakes and mountains, the characteristics of her language and people have been moulded by movements, large and small, between the two islands since the dawn of human history. The difference between Ulster and the rest of Ireland is one of the most deeply rooted, ancient, and from a literary point of view, most productive facts of early Irish History. Furthermore, Ulster’s bond with Scotland counterbalances her lax tie with the rest of Ireland. To say, once more, that this applies only to modern times and to dialects of English would be to miscalculate grossly. Here too the mould was fixed in ancient times and modern developments continue ancient associations.

We need but think of the ancient British Cruthin Kingdoms in both areas, of the Ulster-Scottish Kingdom of Dalriada from the last quarter of the 5th to the close of the 8th century, of the Scottish Kingdom founded under Gaelic leadership in 842, of Irish relations with the Kingdom of the Hebrides and Argyll from the 12th century, particularly the immigration of Hebridean soldiers (gallowglasses) from the 13th to the 16th century. The Gaelic form of this word, Galloglaigh, (i.e. Gallagher) occurs as a family name in Northern Ireland. Another family name for them is “English” Gallowglasses would later become the mainly Catholic Dutch Blue Guards of William of Orange and the Swiss Guards of the Papacy.

There was a constant coming and going between North East Ireland and Western Scotland. The Glens of Antrim were in the hands of Scottish Macdonalds by1400, and for the next two hundred years Gaelic-speaking Scots came in large numbers. The 17th century immigration of a numerous Scots element need not to be considered outside the preceding series. It has brought for example Presbyterian Scots with names as familiar on this side as McMenemin and Kennedy, who must be considered rather in the light of homing birds.

From October 1690 until May 1691 no military operation on a large scale was attempted in the Kingdom of Ireland. During that winter and the following spring the island was divided almost equally between the contending parties. The whole of Ulster, the greater part of Leinster, and about one third of Munster were now controlled by the Williamites; the whole of Connaught, the greater part of Munster and two or three counties of Leinster were still held by the Jacobites.

Continuous guerrilla activity persisted, however, along the rough line of demarcation. In the spring of 1691, James’s Lord Lieutenant, Tyrconnell, returned to Ireland, followed by the distinguished French general Saint Ruth, who was commissioned as Commander-in-Chief of the Jacobite army. Saint Ruth was a man of great courage and resolution but his name was synonymous with the merciless suppression and torture of the Protestants of France, including those of the district of Orange in the South, of which William was Prince.

The Marquess of Ruvigny, hereditary leader of the French Protestants, and elder brother of that brave Caillemot who had fallen at the Boyne, now joined the Dutch general Ginkell, who was strengthening the Williamite army at Mullingar. Ginkell first took Ballymore where he was joined by the Danish auxiliaries under the command of the Duke of Wurtemburg, and then the strategic town of Athlone.

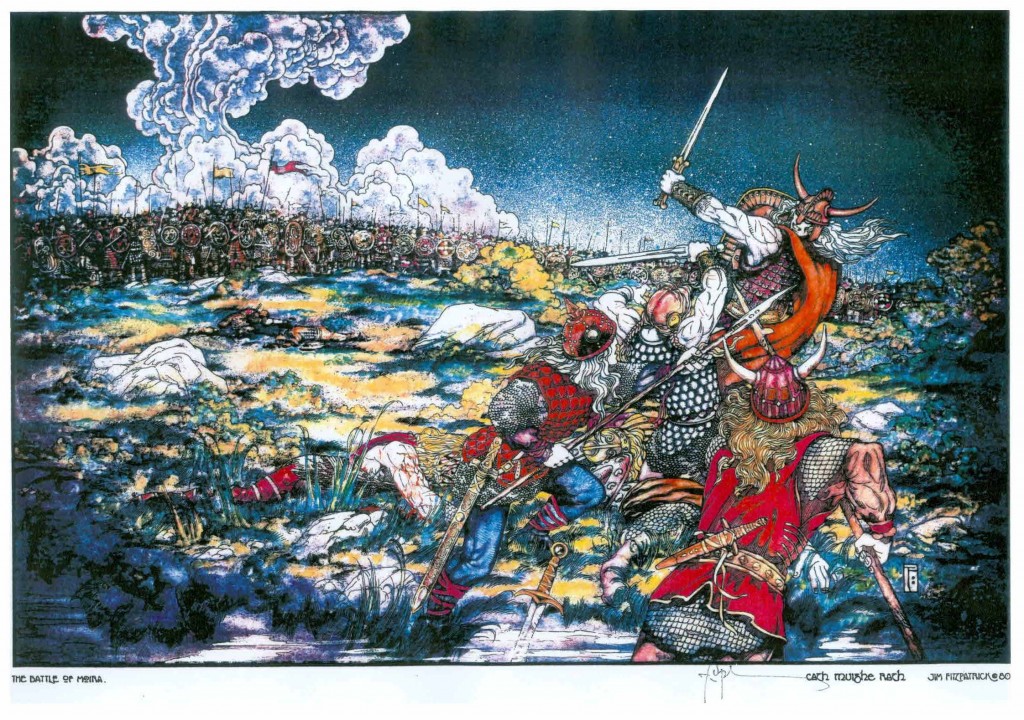

Thus was the stage set for one of the fiercest battles of that age or any other. Determined to stake everything in a final showdown St Ruth pitched his camp about thirty miles from Athlone on the road to Galway. He waited for Ginkell on the slope of a hill almost surrounded by red bog, chosen with great judgement near the ruined castle of Aughrim.

Soon after 6 o’clock on the morning of 12 July, 1691, the Williamite army moved slowly towards the Jacobite positions. Delay was caused, however, by a thick fog which hung until noon and only later in the afternoon did the two armies confront each other.

The Jacobite army of twenty-five thousand men had further protected themselves with a breastwork constructed without difficulty. The Williamites, numbering under twenty thousand, advanced over treacherous and uneven ground, sinking deep in mud at every step. The Jacobites defended the breastwork with great resolution for two hours so that, as evening was fast closing in, Ginkell began to consider a retreat. St Ruth was jubilant and pressed his advantage.

However, Ruvigny and Mackay, with the Huguenot and British Cavalry, succeeded in bypassing the bog at a place where only two horsemen could ride abreast. There they laid hurdles on the soft ground to create a broader and safer path and, as reinforcements rapidly joined them, the flank of the Jacobite army was soon turned. St Ruth was rushing to the rescue when a cannonball took off his head. He was carried in secret from the field and, without direction, the Jacobites faltered. The Williamite infantry returned to their frontal attack with rugged determination and soon the breastwork was carried. The Jacobites retreated fighting bravely from enclosure to enclosure until finally they broke and fled.

This time there was no William to restrain the soldiers. Only four hundred prisoners were taken and not less than seven thousand Jacobites were killed, a greater number of men in proportion to those engaged than in any other battle of that time. Of the victors six hundred were killed, and about a thousand were wounded. If the night had not been moonless and visibility reduced by a misty rain, which allowed Sarsfield to cover the retreat, scarcely a Jacobite would have escaped alive.

Waiting in the wings with his own army was a remarkable character named Balldearg O’Donnell. He had arrived from Spain shortly after the Battle of the Boyne claiming to be a lineal descendant of the ancient “Gaelic” Cruthin kings of Tyrconnell in Ulster. He also claimed to be the O’Donnell ‘with a red mark’ (ball dearg) who, according to ancient prophecy, was destined to lead his followers to victory. Many ordinary Ulster Catholics had flocked to his standard, causing great hostility on the part of Tyrconnell who saw him as a threat to his own earldom.

Balldearg thus remained aloof from the Battle of Aughrim. He proceeded to join the standard of William with 1200 men on 9th September, 1691, and marched to assist in the reduction of the Jacobite town of Sligo. This garrison surrendered on 16th September, 1691, on condition that they were conveyed to Limerick. Balldearg remained loyal to William and later entered his service in Flanders, with those of his men who elected to follow him.

The Battle of the Somme in 1916 has been celebrated by Ulster Protestants as an essential part of their heritage. Yet the sacrifice of young lives in the battlefields of France during the First World War were in reality a uniquely intercommunity one with Protestants, and Catholics, Northerners and Southerners, fighting and dying side by side. There are memorials to the young men from Donegal, Monaghan and Cavan in churches throughout those counties. Furthermore the famous Finner Camp has had a very special place in the commercial, social and historic fabric of south Donegal since it was established in l890.

The valour displayed by the 36th Ulster Division is legendary but the price paid was high. They had lost over 5,500 officers and men. The Inniskillings lost more than any British Regiment of the line has ever lost in a single day. Of the 15th Royal Irish Rifles only 70 men answered their names on that night of the 1st July. The dead accounted for half of the casualties. And Ulster, in this Divisional context included Donegal, Monaghan and Cavan.

The battle dragged on until November. In September it was the turn of the 16th Irish Division to show their gallantry. This division included 5 Ulster battalions and also the 6th Battalion, the Connaught Rangers, which included 600 Ulster men recruited mainly from West Belfast. The 16th Irish Division is most predominately identified the assaults on the villages of Guillemont and Guinchy. Lieutenant- Colonel W Shooter wrote: “The conditions in which the Irishmen had to advance were appalling. The whole of this area was the scene of complete desolation and odious mud. Movement over the ground in such conditions required a supreme effort, apart altogether from the fierce hurricane of machine gun and artillery fire which the enemy brought to fear in the advancing troops. Nevertheless the advancing Fusiliers and Riflemen hacked their way forward with great determination and traditional Irish dash. In spite of the most severe casualties they drove the Germans from their positions inflicting heavy loss on the defenders and taking many prisoners.”

The Great War saw the sacrifice of a whole generation of Europe’s young men led like lambs to the slaughter by politicians and generals. Nevertheless the War provided proof that Ulster men of all persuasions could unite in the face of adversity. One veteran of the Ulster division Tommy Jordan witnessed such mutual aid even while in the trenches.

“I remember too we were in a village close to the men of the 16th Irish Division and a lot of Australians. This Australian, a great fellow but very overbearing,… anyway something happened. There was a row between some of our people and these Australians. HHow the Irish brigade got word of it nobody knew but down they came and beat up the Australians. Now I saw fellows arm- in- arm afterwards. Fellows of the 11th Enniskillings with their orange and purple badges and the other fellas with their great big green badges on their arm.”

Yet, in a sense the Battle of the Somme signifies the rebirth of the Ulster Nation.The Battle became Northern Ireland. We are a very fortunate people in Ulster. The marvellous diversity of both Irish and British culture has been accorded to us. We should all be proud of what we are.Through the chair of our Ullans Academy, Helen Brooker, my colleague in Pretani Associates, we, and here I include our Secretary John Laverty and our Treasurer Jim Potts, who are with us tonight, are developing the vision of Common Identity promoted over the years by our Patron Andy Tyrie, to take us at last beyond the religious divide.