Peoples of Northern Britain according to Ptolemy’s map

The Epidian Cruthin or Epidii (Greek Επίδιοι) were an ancient British people, known from a mention of them by Ptolemy the geographer c. 150.The name Epidii includes the Gallo-Brittonic root epos, meaning horse (Compare with Old Gaelic ech). It may, perhaps, be related to the Horse-goddess Epona. They inhabited the modern-day regions of Argyll and Kintyre, as well as the islands of Islay and Jura, from which my great-granny Lambey was sprung. They were Brittonic or Old British in speech, although later Gaelicised to become part of the heartland of the kingdom of Dalriada (Dál Riata).

Dalriada was founded by Gaelic-speaking people from Ulster, including Robogdian Cruthin, who eventually Gaelicised the west coast of Pictland, according to the Venerable Bede, by a combination of force and treaty. The indigenous Epidian people however remained substantially the same and there is no present archaeological evidence for a full-scale migration or invasion. The inhabitants of Dalriada are often referred to as Scots (Latin Scotti), a name originally used by Roman and Greek writers for the Irish who raided Roman Britain. Later it came to refer to Gaelic-speakers in general, whether from Ireland or elsewhere.The name Dál Riata is derived from Old Gaelic. Dál means “portion” or “share” (as in “a portion of land”) and Riata or Riada is believed to be a personal name. Thus, Riada’s portion.

In Argyll Dalriada consisted initially of three kindreds; Cenél (Clan) Loairn (kindred of Loarn) in north and mid-Argyll, Cenél nÓengusa (kindred of Óengus) based on Islay and Cenél nGabráin (kindred of Gabrán) based in Kintyre; a fourth kindred, Cenél Chonchride in Islay, was seemingly too small to be deemed a major division. By the end of the 7th century another kindred, Cenél Comgaill (kindred of Comgall), had emerged, based in eastern Argyll. The Lorn and Cowal districts of Argyll take their names from Cenél Loairn and Cenél Comgaill respectively, while the Morven district was formerly known as Kinelvadon, from the Cenél Báetáin, a subdivision of the Cenél Loairn.

The kingdom reached its height under Áedán mac Gabráin (r. 574–608), but its growth was checked at the Battle of Degsastan in 603 by Æthelfrith of Northumbria. Serious defeats in Ireland and Scotland in the time of Domnall Brecc (d. 642) ended Dál Riata’s “golden age”, and the kingdom became a client of Northumbria, then subject to the Picts (Caledonian Cruthin). There is disagreement over the fate of the kingdom from the late eighth century onwards. Some scholars have seen no revival of Dalriada after the long period of foreign domination (after 637 to around 750 or 760), while others have seen a revival of Dalriada under Áed Find (736–778), and later Kenneth Mac Alpin (Cináed mac Ailpín, who is claimed in some sources to have taken the kingship there in c.840 following the disastrous defeat of the Pictish army by the Danes): some even claim that the kingship of Fortriu was usurped by the Dalriadans several generations before MacAlpin (800–858). The kingdom’s independence ended in the Viking Age, as it merged with the lands of the Picts to form the Kingdom of Alba.

Among the royal centres in Dalriada, Dunadd, which we visited with our Dalaradia organisation recently, appears to have been the most important. It has been partly excavated, and weapons, quern-stones and many moulds for the manufacture of jewellery were found in addition to fortifications. Other high-status material included glassware and wine amphora from Gaul, and in larger quantities than found elsewhere in Britain and Ireland. Lesser centres included Dun Ollaigh, seat of the Cenél Loairn kings, and Dunaverty at the southern end of Kintyre, in the lands of the Cenél nGabráin. The main royal centre in Ulster appears to have been at Dunseverick (Dún Sebuirge).

There are no written accounts of pre-Christian Dalriada, the earliest records coming from the chroniclers of Iona and Irish monasteries. Adomnán’s Life of St Columba implies a Christian Dalriada Whether this is trueor not cannot be known. The figure of Columba looms large in any history of Christianity in Dalriada. Adomnán’s Life, however useful as a record, was not intended to serve as history, but as hagiography. We are fortunate that the writing of saints’ lives in Adomnán’s day had not reached the stylised formulas of the High Middle Ages, so that the Life contains a great deal of historically valuable information. It is also a vital linguistic source indicating the distribution of Gaelic and P-Celtic or British placenames in northern Scotland by the end of the 7th century. It famously notes Columba’s need for a translator when conversing with an individual on Skye. This evidence of a non-Gaelic language is supported by a sprinkling of British placenames on the remote mainland opposite the island.

Columba’s founding Iona within the bounds of Dalriada ensured that the kingdom would be of great importance in the spread of Christianity in northern Britain, not only to Pictland, but also to Northumbria, via Lindesfarne, to Mercia, and beyond. Although the monastery of Iona belonged to the Cenel Conaill of the Venniconian Cruthin of modern Donegal, and not to Dalriada, it had close ties to the Cenél nGabráin, (ties which may make the annals less than entirely impartial), in the territory of the Cenél Loairn, and was sufficiently important for the death of its abbots to be recorded with some frequency. Applecross, probably in Pictish territory for most of the period, and Kingart on Bute, are also known to have been monastic sites, and many smaller sites, such as on Eigg and Tiree, are known from the annals. In Ireland, Armoy was the main ecclesiastical centre associated with Saint Patrick and with Saint Olcán, said to have been first bishop at Armoy. An important early centre, Armoy later declined, overshadowed by the monasteries at Movilla (Newtownards) and the greatest of all, Bangor. The importance of Bangor cannot be over-estimated, yet it has been neglected due to the combined influences of Irish, Scottish and English nationalist academics.

The history of Dalriada, while unknown before the middle of the 6th century, and very unclear after the middle of the 8th century, is relatively well recorded in the intervening two centuries, There is no doubt that Ulster Dalriada was a lesser kingdom of Ulaid. The Kingship of Ulster was dominated by the Dal Fiatach of North Down and Ards and contested by the Cruthin kings of Dalaradia, who maintained that they, and not the Dal Fiatach, were the true Ulstermen.

In 575, Columba fostered an agreement between Áedán mac Gabráin and his kinsman Áed mac Ainmuirech of the Cenél Conaill at Druim Cett. This alliance was likely precipitated by the conquests of the Dál Fiatach king Baetan mac Cairill. Báetán died in 581, but the Ulaid kings did not abandon their attempts to control Dalriada.The kingdom of Dalriada reached its greatest extent in the reign of Áedán mac Gabráin. It is said that Áedán was consecrated as king by Columba. If true, this was one of the first such consecrations known. As noted, Columba brokered the alliance between Dalriada and his kindred ,the Venniconian Cruthin of Cenél Conaill , of the so-called “Northern Uí Néill”.

This pact was successful, first in defeating Báetan mac Cairill, then in allowing Áedán to campaign widely against his neighbours, as far afield as Orkney and the Pictish lands of the Maeatae, on the River Forth. Áedán appears to have been very successful in extending his power, until he faced the Bernician king Æthelfrith at Degsastan c. 603. Æthelfrith’s brother was among the dead, but Áedán was defeated, and the Bernician kings continued their advances in southern “Scotland”. Áedán died c. 608 aged about 70. Dalriada did expand to include Skye, possibly conquered by Áedán’s son Gartnait. It appears, although the original tales are lost, that Fiachnae mac Báetáin (d. 626), Dalaradian King of Ulster, was overlord of both parts of Dalriada. Fiachnae campaigned against the Northumbrians, and besieged Bamburgh, and the Dalriadans will have fought in this campaign.

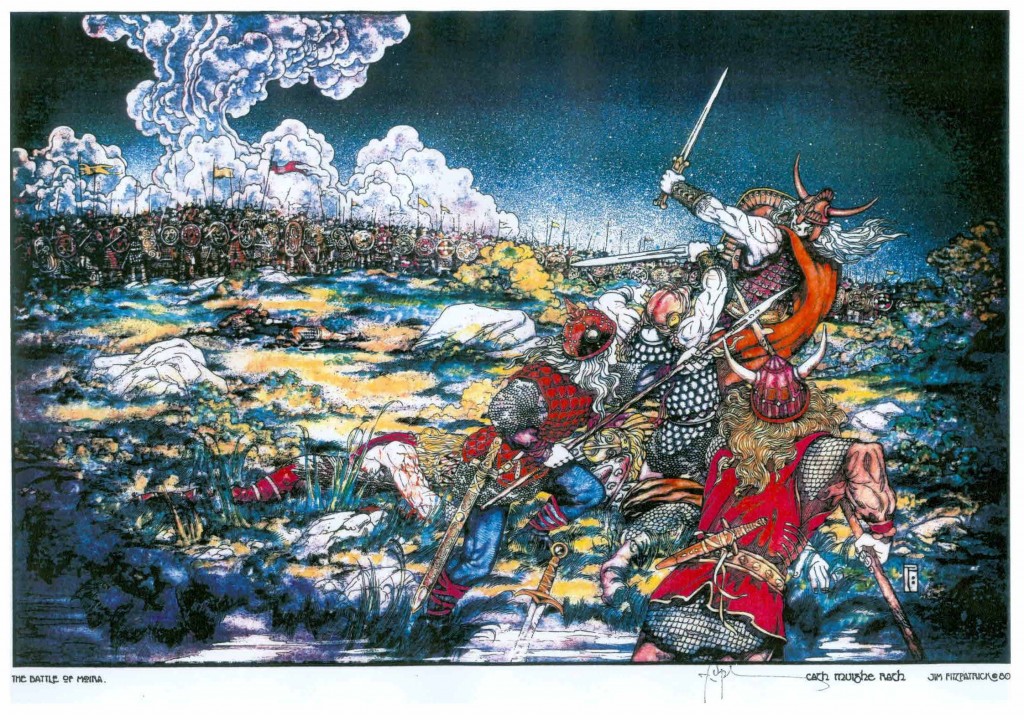

Dalriada remained allied with the “Northern Uí Néill” until the reign of Domnall Brecc, who reversed this policy and allied with Congal Cláen of the Dalaradians. Domnall joined Congal in a campaign against Domnall mac Áedo of the Cenél Conaill, the son of Áed mac Ainmuirech The outcome of this change of allies was defeats for Domnall Brecc and his allies on land at Mag Rath (Moira, County Down) and at sea at Sailtír, off Kintyre, in 637. This, it was said, was divine retribution for Domnall Brecc turning his back on the alliance with the kinsmen of Columba. Domnall Brecc’s policy appears to have died with him in 642, at his final, and fatal, defeat by Eugein map Beli of Alt Clut at Strathcarron, for as late as the 730s, armies and fleets from Dalriada fought alongside the “Uí Néill”.

To be continued

© Pretani Associates 2014