The exemplary missionary priest Tom O Connor has written recently: “Faechno was succeeded at Tara by yet another Dal nAraidi (Dalaradia) Overking of the Cruthin of Ulster and Scotland, namely his own grandson Congal Caech (Claen), a historic fact fossilised in “Bech Bretha”. He fell at the great watershed Battle of Moira, Co Down, in 637. The law-tract on bees, “Bech Bretha”, preserves the true “untampered version”. It has profound historical implications corroborating Cruthin claims that their kings, and theirs alone, ruled at Tara up to the Battle of Moira in 637. The Battle of Moira ended the Cruthin tenure of the overkingship of Northern Ireland and Scotland from Tara. This fact and its attendant ramifications are vital to the rediscovery of the suppressed and silenced history of Iron Age and early Christian Ireland. The rising roar of the Ui Neill warlords smothered the humble, truthful, voice of the Cruthin. Thereafter all Ireland rode on the back of a fiendish fraud reverberating with profuse repercussions, civil, social, religious, cultural and historical, affecting all Ireland, past, present and future. Ireland is still being taken for a ride”.

A native of Kiltullagh, Athenry, Tom O Connor has spent almost 50 years researching the history and geopolitics of Iron Age Ireland, notably early Connacht. He spent over thirty years as a missionary priest in Malaysia and his credentials are impeccable. His books, Turoe & Athenry: Ancient Capitals of Celtic Ireland and Hand of History, Burden of Pseudo-History, present a Celtic royal complex, unprecedented in Ireland for its size and layout, but similar to Belgic centres of power, called oppida by Julius Caesar, in SE England and on the Continent, centered on Turoe in County Galway, site of the famous Turoe Stone. Among the finest example of La Tene Celtic stone art in Europe, the stone was set on Turoe hill (Cnoc Temhro). According to Tom, it is part of a hitherto unrecognised royal sanctuary at the core of a Belgic-like oppidum defensive system of linear embankments, connected with the supposed Celtic invasion of Ireland. His work has received local and national interest – especially since the construction of the M6 Motorway (Ireland) through many of the sites, another Southern attempt to destroy archaeological evidence – yet received little endorsement from so-called professional historians and archaeologists. Support for my work has been a non licet for these charlatans.

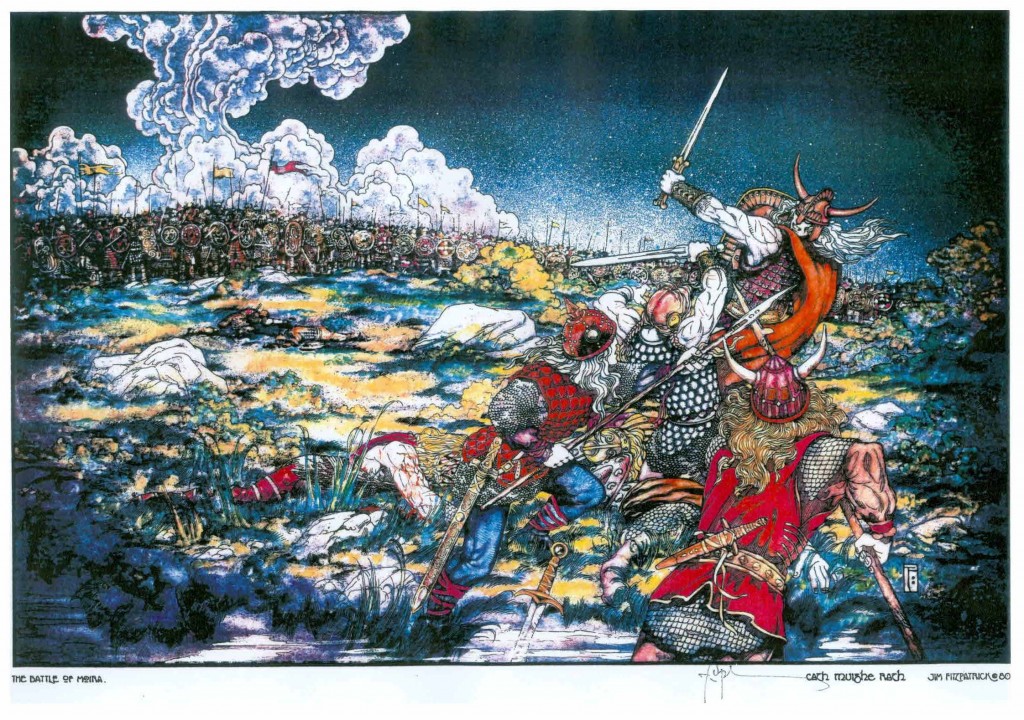

This is the original of an article for you on the Battle of Moira, which I commemorate every 24th June. I have anglicised some of the names for the Ulster Scot. . I append a painting on the Battle by my friend Jim Fitzpatrick, whom I commissioned to do the cover of my book on Sir Samuel Ferguson’s Congal, which I entitled The Battle of Moira.

The Battle of Moira

The Battle of Moira in County Down was, according to the great Belfast poet and scholar Sir Samuel Ferguson, “the greatest battle, whether we regard the numbers engaged, the duration of combat, or the stake at issue, ever fought within the bounds of Ireland…….there appears reason to believe that the fight lasted a week….. (near) the Woods of Killultagh, to which, we are told the routed army fled, great quantities of bones of men and horses were turned up in excavating the line of the Ulster Railway”.

The Battle is mentioned prominently in the ancient Irish Annals, but that such a significant event remains so little known at the present time is as a result of the fact that it occurred long before the arrival in Ireland of the Anglo-Normans, and thus has received little attention from the English and Irish historians. The story of Suibhne Geilt, king of Dalaradia, who took part in the Battle, was, however, to have a lingering effect on Irish literature, most notably in Sweeney’s Frenzy by J G O’Keeffe, At-Swim-Two-Birds by Flann O’Brien and Sweeney Astray by Seamus Heaney.

Set as Ulster is at the North Eastern corner of Ireland, facing Britain across a narrow sea and separated from the rest of Ireland by a zone of little hills known as Drumlins, by marshlands and by mountains, the characteristics of her language and people have been moulded by movements large and small between the two islands since the dawn of human history. The difference between Ulster and rest of Ireland is therefore one of the most constant facts of early Irish history and Ulster’s bond with Scotland counterbalances her lax tie with the rest of Ireland. Just as the mould was fixed in olden times, modern developments have continued ancient associations.

Thus there were the old ancient British, Pretani or Cruthin Kingdoms in both areas, Dalaradia in Antrim and Down and Pictavia in Northern Britain. There was the Ulster Scottish Kingdom of Dalriada from the last quarter of the fifth till the close of the eighth century and the Scottish Kingdom founded under Gaelic leadership in 842. There were continuing Irish relations with the Kingdom of the Hebrides in Argyle from the 12th Century, particularly with the immigration of Hebridean soldiers or galllowglasses from the 13th to the 16th century. The Glens of Antrim were in the hands of the Scottish MacDonalds by 1400 and for the next 200 years Gaelic speaking Scots came in large numbers. The 17th century immigration of a numerous Scots element need not therefore be considered outside the proceeding series, since it has brought for example Presbyterian Scots with names as familiar as Kennedy, who must be considered rather as people who have returned home.

In 563 AD the power of the ancient British Cruthin in the West of Ulster had been crushed at the Battle of Moneymore and they suffered a further defeat in 579 near Coleraine. Yet they still clung firmly to the territory which they retained east of the Bann river, and as long as their resistance remained, the Gaelicised “Uí Néill” could never call themselves Kings of Ulster.

In 627 Congal Cláen of the Cruthin became over-King of all Ulster. He had received his name of Cláen or half blind since he had been stung in the eye by a bee. In 628 he killed the “Uí Néill” high King Suibne Menn of the Clan Owen, who was replaced as High King by Domnall, of the Clan Connall (Gaelicised Cruthin) . In 629 Domnall defeated Congal and his autonomous Cruthin at the Battle of Dun Ceithirnn in Londonderry, but internal dissention among the “Uí Néill” allowed Congal a respite and he fled to Scotland or Alba, where he began constructing a formidable coalition of forces.

In 637 therefore, he returned with a large army containing contingents of Scots, Picts, Anglo-Saxons (English) and Britons (Welsh). The outcome was that on Tuesday 24th June in that year of 637 was fought the Great Battle of Moira, when Domnall of the “Uí Néill” and his forces were confronted by the British Ulstermen and their allies. With Domnall’s victory , however, and the death of Congal in the Battle, any pretentions the Ulstermen had of undoing the Uí Néill gains were dashed and from that point on the “Uí Néill” were to become the dominant power in the North.

On the same day a naval engagement between the Dalriadans and Clan Owen on the one side and the Clan Connall forces of Domnall on the other off the Mull of Kintyre resulted in the splitting of Irish and Scottish Dalriada. Despite continuing aggression, the Ulstermen continued to put up a stubborn resistance and in 1004 another great battle was fought at Cráeb Tulcha or Crew Hill (Glenavy) in which the Cruthin King, the Ulidian King and many Princes of Ulster were killed. Indeed complete disaster was possibly only averted because the victorious “Uí Néill” King was himself one of the fatalities. In 1099 a battle was fought between the same parties at the same place where the invaders again gained the day. After the battle the victors cut down the Cráeb, the sacred tree of Ulster. Nevertheless the Ulstermen prevented the supposed descendents of the “Uí Néill”, the O’Neills, gaining unchallenged control of Ulster and it was not until 1364 that a member of that Clan could finally style himself King of Ulster in the eyes of the learned classes.

Subject to continuing pressure by the “Uí Néill”, the Cruthin were to migrate to the old British Kingdoms of Aeron (Ayr) and Rheged (Stranraer), where in the old Scotch or Ullans dialect they became known as Creenies. The impact of the 17th Century Hamilton/Montgomery settlement really lay in its success as a blueprint for plantation in general, and especially the later official Plantation of Ulster in 1610. But it was the 105 day siege of Londonderry which lasted from the 18th April 1689 until 28th July 1689, the Battle of the Boyne on 1st July 1690 and the Battle of Aughrim on 12th July 1691, which allowed the stabilisation of Scottish settlement in Ulster. Indeed only as a result of the Williamite victory was Scottish migration resumed and was able to reach its peak during the 1690’s, in part as a result of cheap land in Ireland after the British revolution and also as a result of severe famine in Scotland during the latter years of that decade. The level of migration in that period was somewhere between 50,000 to 70,000 Scots, more than three times as many settlers as during the reign of James IV of Scotland and I of England. Thus at last, the descendants of the Cruthin people, the ancient British, were allowed to return to their homeland and their right to be there was finally sealed by their sacrifice at the Battle of the Somme on 1st July 1916.