Helen’s Tower, Conlig

Helen’s Tower was designed in 1848 by William Burn in the Scottish style and construction was completed in October 1861. It was part of an ambitious landscape project by Lord Dufferin covering the five miles between it and the coast at Helen’s Bay, to aid local labourers made destitute by the Great Famine. The tower was eventually named in honour of his mother Helen, who was a grand daughter of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the great Irish playwright, orator and politician.

It was built as a Gamekeeper’s residence but became a retreat for his mother who suffered from cancer of the breast and poems were written in its honour by Tennyson, Kipling, Argyll and other luminaries of the nineteenth century literary world. Like most children in Conlig I loved to visit the caretaker Mrs Bruce as a boy and the Bluebell and Primrose plantin around it. In an alcove of the Tower was a wishing seat, where my mother sat when she was pregnant with me.

Ulster Tower, Thiepval

However, the tower took on an unforeseen poignancy after the battle of the Somme in 1916. The land around the tower had been used as a training camp by the 36th (Ulster) Division prior to their embarkation from Belfast for France and, for those soldiers, Helen’s Tower would have been a lasting image as they sailed out of Belfast Lough. For this reason, in 1921, funds were raised by the families of the fallen and an exact replica, the Ulster Tower, built on the battlefield at Thiepval.

The commemoration to mark the 170th anniversary of the Great Famine has just been held at the Albert Basin in Newry, County Down. Attended by ministers from the Irish government and the Northern Ireland Executive, it was the high point of a week of talks, walks, music and drama about the tragedy. In her remarks, the Irish Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht, Heather Humphreys, recalled how in Newry workhouse all the health professionals died of fever. “A point that has struck me forcibly is how the legacy and memory of the famine is deeply ingrained in the collective memory of the host community in Newry,” she said.

The Great Famine of 1845-51 has the grim distinction of being the most costly natural disaster of modern times. Ireland had witnessed a massive surge in population from 2.6 to 8.5 million by 1845 when blight struck the staple food of the masses – the potato. Some 80% of this teeming population lived on the land, making Ireland one of the most densely populated countries in Europe. Under a land system where most of the land was owned by the great Plantation landlords, vast numbers of the poorest ‘cottier’ class lived on ‘potato gardens’, often sub-divided among their sons. By the 1840s, close on two-fifths of the population were totally dependant on the potato and it was the major food-source of the rest.

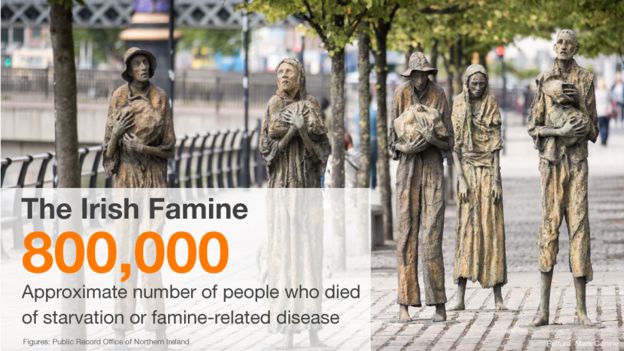

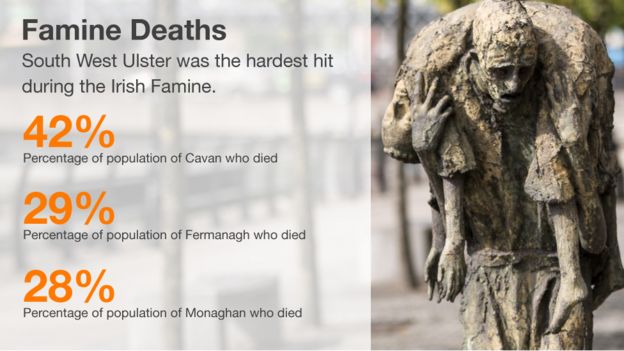

Between 1845 and 1849, the potato crop failed in three seasons out of four. The result was starvation and the spread of the “road disease” – dysentery, typhus and cholera.One million people died of hunger and disease during the crisis and more than one million emigrated, mainly to the United States – often in the notorious ‘coffin ships’, so-called because many people died because of the terrible conditions during the crossing. In dealing with the crisis, the government introduced ‘Outdoor Relief’ – the provision of soup kitchens in distressed area and public works, such as the building of roads and harbours. However, these measures were woefully inadequate. The country’s workhouses were grossly overcrowded, adding to the vast mortality. The claim that the Famine did not affect Ulster has been debunked by recent historical research. Between 1845-51 Ulster’s population fell by 340,000, a drop of 15.7% compared with 19.9% for the whole of lreland.

The greatest losses of population were in the south Ulster counties of Cavan, Fermanagh and Monaghan. Fermanagh lost almost 30% of its inhabitants. Tyrone, Antrim and Armagh were close to the national average with rates of around 15%. Surprisingly, research shows that the events from 1845 to 51 affected normally prosperous parts of the north-east, including Belfast, north Down and particularly the linen triangle of north Armagh. By December 1846 the first deaths from starvation were reported in the local press. By early 1847 cholera was spreading in Fermanagh, with the Erne Packet reporting: “In Garvary Wood hundreds of corpses are buried, they were the victims of cholera and their relatives too weak to carry them to the graveyard.” One of the most surprising aspects of the Famine was its searing impact on traditionally prosperous parts of eastern Ulster. Particularly hard-hit was the Lurgan-Portadown linen triangle of north Armagh.

Image copyright Picture: Mark Carline

Image copyright Picture: Mark Carline Lurgan Workhouse in 1847 recorded the third highest mortality of any workhouse in Ireland. An inquiry blamed the crisis on overcrowding and the fact that the corpses of fever victims were interred beside the workhouse well. The result was a cycle of death. In normally prosperous Newtownards, there were queues at the soup kitchen of “emaciated and half-famished souls”, covered with rags. In 1847 the worst affected areas in Down included the Mournes and the fishing port of Kilkeel. The reactions of the landlords varied. Not all were as compassionate as the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava Lord Londonderry, the largest landowner in north Down, rejected rent reductions due to “personal inconvenience” and was much criticised.

Newry – the site of the all-island Famine Commemoration – became a key centre of emigration from south Ulster, with vessels carrying thousands direct to Canada and the United States. Among these was the ill-fated ‘coffin ship’, the Hannah, carrying emigrants from South Armagh. Fifty people were drowned when it struck ice near Quebec. The Famine had a traumatic impact on the growing industrial town of Belfast, which attracted large numbers of famished and disease-ridden people from all parts of Ulster. In March 1847, typhus fever swept the town following the arrival in the port of the Swatara, an emigrant ship from Connacht.

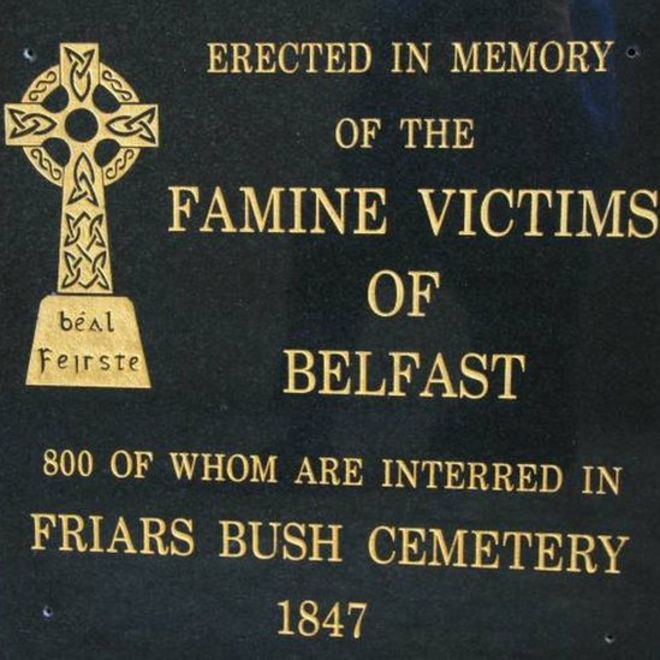

The Plaguey Hill at Friar’s Bush Graveyard in south Belfast is a grim cenotaph commemorating some 800 victims of ‘Black ’47’.