JRR Tolkien’s early story The Story of Kullervo has just been published for the first time. The dark tale reveals that Tolkien’s Middle Earth was inspired not only by the mythology of ancient Pretania. the British Isles… but also by Finland.

“Hapless Kullervo,” Tolkien called him. Kullervo, an orphan boy raised into slavery, a tragic hero who commits incest in the dark forests of Karelia and hurls himself on his own blade.

JRR Tolkien first discovered the tale as a schoolboy in Birmingham. His father had died when he was a young child, and his mother passed away when he was 12, so he had been an orphan himself for some years when he came across the Finnish epic Kalevala – and within it the tale of Kullervo – during his final year at school. It had a huge impact.

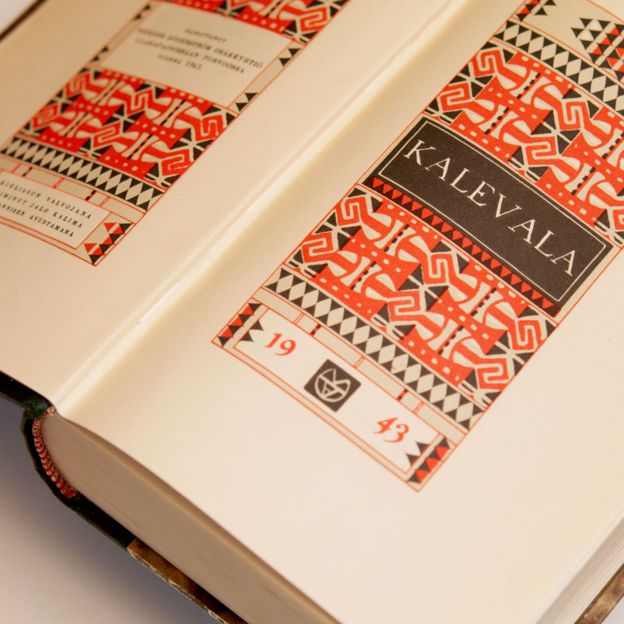

Kullervo’s tale is just one of 50 songs in the Kalevala, an epic of 22,795 verses telling the story of the Sampo, a magical object that bestows power on whoever possesses it. Tolkien used numerous plot elements from the Kalevala in his own novels – a powerful magical object, incest, battles between brothers, and orphan heroes setting out on quests. In The Silmarillion (begun in 1914, but only published after his death), Tolkien turns Kullervo into Turin Turambar, the warrior hero.

Since the 12th Century Finland had been ruled by Sweden, and then Russia, only gaining independence in 1917. During the last century of foreign rule, the Kalevala – assembled by a physician, folklorist Elias Lönrot (1828-1884), in the course of twelve research trips (1828-1844), walking or skiing around Karelia writing down the poems people sang to him – became a powerful symbol of Finnish identity. Lönrot wove the songs of the unlettered folksingers into a long narrative poem, centred around the great cultural heroes of Finnish mythology, the sage-and-singer Väinämöinen, the smith Ilmarinen, the brash eroticist and adventurer Lemmminkäinen and the tragic outsider Kullervo.

The Kalevala has been fully translated into 35 and partially translated into 100 languages. My favourite in English is that by Eino Friberg, presented to me by the Finnish community in Seattle. The William Forsell Kirby translation Kalevala, Land of the Heroes , which I have owned in the Everyman’s Library edition since I was a little boy, is in monotonously regular and unchanging trochaic tetrameter. Friberg’s translation, on the other hand, like that of the Finnish original, consists of verse with metrical variety and has fully captured the sometimes homely, sometimes humorous, and always enchanting nature of the great poem..

Having fallen for the Finnish epic, the language-loving Tolkien was not content to read it only in translation. Once at Oxford, he found a book of Finnish grammar – and borrowed it several times. Although he never visited Finland and does not seem to have met any native speakers, Tolkien became captivated by the language. In 1955 he told the poet WH Auden that discovering Finnish had been like “entering a complete wine-cellar filled with bottles of an amazing wine of a kind and flavour never tasted before”. But he had to admit that he had “never learned Finnish well enough to do more than plod through a bit of the original like a schoolboy…”

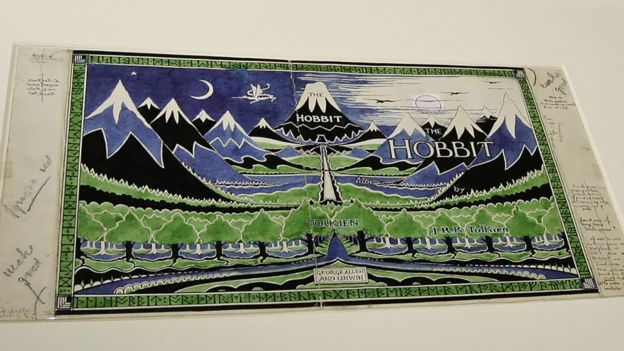

Tolkien was intrigued by and loved the long vowel sounds of Finnish and the umlaut accents. Fictional Elvish phrases such as “Mindon Eldalieva” (“Lofty Tower of the Elvish-people”) and “Oron Oiolosse” (“Ever Snow-white Peak”) use the sound and style of the language.Tolkien’s invented Elvish language of Quenya is incredibly complex. When writing The Hobbit in the 1930s and The Lord of the Rings (published in 1949), Tolkien included irregular verbs and archaic phrases, showing how his invented language had changed over time – the Quenya used by Aragorn differs from the older Quenya used by his ancient ancestors, in which the influence of Finnish is much stronger.

For Tolkien the invented language came first, and Middle Earth second. The much-loved adventures of Bilbo and Frodo were a chance for Tolkien the philologist to bring his new language to life. Tolkien realised with The Story of Kullervo that language, culture and mythology are inextricably linked, He had invented a language – and so he invented a mythology.But Finnish sources were not the only ones Tolkien used. Others include the romantic medieval images of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, the scenery of the Welsh countryside, the adventures of King Arthur, the German epics, Ulster mythology and his own traumatic experiences in the Battle of the Somme between July and November 1916.

Perhaps the most Finnish aspect of Tolkien’s writing is the mood. There is a strain of deep tragedy and pessimism that runs through Tolkien’s work, even The Hobbit and certainly Lord of the Rings. The Story of Kullervo is without a doubt the darkest story he ever wrote. It is our first experience of that darkness.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus performed Sibelius’ Kullervo at the BBC Proms on Saturday 29 August.