While Irish missionaries were spreading the message of Christianity throughout Europe the Irish at home had not allowed themselves to be deflected from their proclivity for martial conflict. Around 450, after Emain Macha had been destroyed, or abandoned, as a result of the initial “Uí Néill” advance, the Ulstermen had retreated east, and in this reduced kingdom of Ulster they attempted to stabilise their power, with the erection of the “Dane’s Cast” earthworks as a visible reminder to their adversaries that they were in no respects a spent force. The Cruthin confronted the “Uí Néill” in 563 at the battle of Móin Dairi Lothair (Moneymore). However, seven kings of the Cruthin were killed in this battle, and the way was open for the “Northern Uí Néill” victors to expand into what is now County Londonderry.

While Irish missionaries were spreading the message of Christianity throughout Europe the Irish at home had not allowed themselves to be deflected from their proclivity for martial conflict. Around 450, after Emain Macha had been destroyed, or abandoned, as a result of the initial “Uí Néill” advance, the Ulstermen had retreated east, and in this reduced kingdom of Ulster they attempted to stabilise their power, with the erection of the “Dane’s Cast” earthworks as a visible reminder to their adversaries that they were in no respects a spent force. The Cruthin confronted the “Uí Néill” in 563 at the battle of Móin Dairi Lothair (Moneymore). However, seven kings of the Cruthin were killed in this battle, and the way was open for the “Northern Uí Néill” victors to expand into what is now County Londonderry.In the great bog of Daire-lothair —

The cause of a contention for right —

Seven Cruthin Kings, including Aedh Brec (Freckled Hugh).

The battle of all the Cruthin is fought,

[And] they burn Eilne (Ballymoney).

The battle of Gabhair-Lifè is fought,

And the battle of Cul-dreimne.

Two years later the Cruthin over-king of Ulster, Aed Dub mac Suibni (Dark Hugh Mac Sweeney), slew the “Northern Uí Néill” king, Diarmait mac Cerbaill. A battle is also recorded between the Cruthin and the Uí Néill near Coleraine in 579. However, it was to be at the great battle of Moira in 637 that the Ulstermen were to make their most determined effort to call a halt to “Uí Néill” expansion.

Congal Cláen, possibly the greatest of all Cruthin kings, became over-king of Ulster in 627. In 628 he slew Suibne Menn, the “Uí Néill” “high-king”, but was in turn defeated by the new “high-king” at Dún Ceithirn in Derry two years later (the battle which Columba’s biographer tells us the saint had prophesied to Comgall, the Cruthin abbot of Bangor).

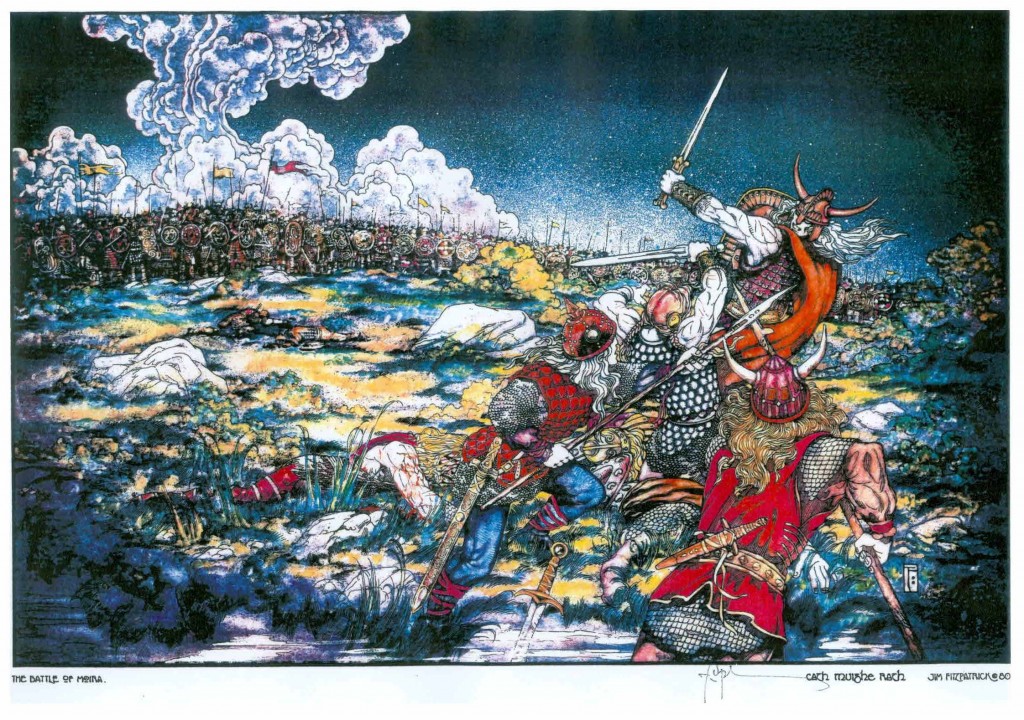

By 637, however, Congal had managed to gather around him a powerful army, which included not only his Ulstermen, but, according to Colgan, contingents of Picts (Scotland), Anglo-Saxons (English) and Britons (Welsh). The battle, as depicted in later Bardic romances, seems to have been a ferocious affair, and as well as the land confrontation it included a naval engagement.

The Annals of Tigernach record the battle as follows:

AD 637. The Battle of Magh Rath, gained by Domnall, son of Aed, and by the sons of Aed Sláine — but Domnall at this time ruled Temoria — in which fell Congal Caech king of Ulaidh and Faelan, with many nobles; and in which fell Suibne, son of Colmán Cuar.

In 1872, Sir Samuel Ferguson — born in 1810 and the finest poet of 19th century Ireland — published his masterpiece Congal, based on the Bardic romance ‘Cath Muighe Rath’ (Battle of Moyra). Ferguson’s poem is in the grand epic style of the old Irish bards, and it is easy to imagine that this is how they too would have described the mortally wounded king, as he staggered from the battlefield, half-conscious and little knowing what was transpiring around him:

But, rapt in darkness and in swoon of anguish and despair,

As in a whirlwind, Congal Cláen seemed borne thro’ upper air;

And, conscious only of the grief surviving at his heart,

Now deemed himself already dead, and that his deathless part

Journeyed to judgement; but before what God’s or demon’s seat

Dared not conjecture; though, at times, from tramp of giant feet

And heavy flappings heard in air, around and underneath,

He darkly surmised who might be the messenger of death

Who bore him doomward: but anon, laid softly on the ground,

His mortal body with him still, and still alive he found.

Loathing the light of day he lay; nor knew nor reck’d he where;

For present anguish left his mind no room for other care;

All his great heart to bursting filled with rage, remorse and shame,

To think what labour come to nought, what hopes of power and fame

Turned in a moment to contempt; what hatred and disgrace

Fixed thenceforth irremovably on all his name and race…

Then Congal raised his drooping head, and saw with bloodshot eyes

His native vale before him spread; saw grassy Collin rise

High o’er the homely Antrim hills. He groaned with rage and shame.

“And have I fled the field,” he cried; “and shall my hapless name

“Become this byword of reproach? Rise; bear me back again,

“And lay me where I yet may lie among the valiant slain.”

In an article reviewing Reeves’ Ecclesiastical Antiquities, Ferguson, who typified the Ulster intellectual of his day — intensely proud of his ‘Gaelic’ heritage, but without the rancour of the xenophobe — wrote:

“We are here upon the borders of the heroic field of Moyra, the scene of the greatest battle, whether we regard the numbers engaged, the duration of combat, or the stake at issue, ever fought within the bounds of Ireland. For beyond question, if Congal Cláen and his Gentile allies had been victorious in that battle, the re-establishment of old bardic paganism would have ensued. There appears reason to believe that the fight lasted a week; and on the seventh day Congal himself is said to have been slain by an idiot youth, whom he passed by in battle, in scorn of his imbecility. All local memory of the event is now gone, save that one or two localities preserve names connected with it. Thus, beside the Rath of Moyra, on the east, is the hill Cairn-Albanach, the burial-place of the Scottish princes, Congal’s uncles; and a pillar-stone, with a rude cross, and some circles engraved on it, formerly marked the site of their resting-place. On the other hand, the townland of Aughnafoskar probably preserves the name of Knockanchoscar, from which Congal’s druid surveyed the royal army, drawn up in the plain below, on the first morning of the battle. Ath Ornav, the ford crossed by one of the armies, is probably modernised in Thorny-ford, on the river, at some miles distance. On the ascent to Trummery, in the direction of the woods of Killultagh, to which, we are told, the routed army fled, great quantities of bones of men and horses were turned up in excavating the line of the Ulster Railway which passes close below the old church.”

To be continued