|

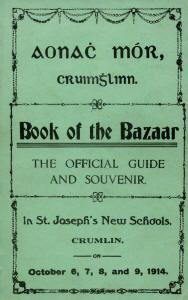

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, OPENING CEREMONY

|

Foreword

The Grand Bazaar and Fancy Fair in the New Schools, Crumlin may seem an unlikely title to arouse the enthusiasm of the local historian, but one has only to peruse this book for a few moments in order to realise its importance. First published in 1914, this book has been virtually unobtainable in recent years and one will search in vain among the book shelves of the Linenhall Library for a copy. The Killultagh Historical Society have always maintained that it is vital to make accessible to the general public all out-of-print publications relevant to our area. In fact, it has taken the Society two years to obtain a copy in good enough condition to facilitate a reprint.

Within this book you will find an Historical Sketch of the Parish of Glenavy along with articles on Sir Neal O’Neill and Mrs. M. T. Pender, plus poems and songs relating to Aldergrove, Glenavy and Ballinderry. One of the contributors was Francis Joseph Bigger, that noted antiquarian of Ardrigh, Belfast, who describes Bonnie Portmore in his own inimitable way. The supplement to the book also makes fascinating reading, containing 45 pages of the names of all those who donated money and gifts in aid of the Bazaar.

The Killultagh Historical Society would like to take this opportunity to thank Davidson Books of Spa, Ballynahinch for their advice and expertise in the reprinting of this book and also the Lisburn Arts Advisory Council for the financial assistance which they have given the Society in the past year.

Thomas Lamb, (Honorary Secretary)

This is a facsimile reprint of the original 1914 edition

Davidson Books, 34 Broomhill Road, Spa, Ballynahinch, Co. Down BT24 8QD.

Telephone (0238) 562502

1983

![]()

Unfortunately I do not have a suitable Gaelic font available but when I have been able to obtain one I will reprint these pages where necessary. JGC

HISTORICAL SKETCH

OF

THE PARISH OF GLENAVY.

I. – EXTENT OF THE PARISH.

THE PARISH OF GLENAVY lies along the eastern shore of Lough Neagh. On the north it is separated from the Parish of Antrim by the Donore River, and extends southward into the Civil Parish of Ballinderry beyond Portmore Lough. On the north-east it is separated from Templepatrick by the Clad)’ Water. It is bounded on the east by Tullyrusk, Stoneyford, and Magheragall. On the south-east it extends to within five miles of the town of Lisburn. Measuring, as the crow flies, from the Donore River on the north to Galwey’s Gate on the south, or from Langford Lodge Point on the shore of Lough Neagh to the confines of Ligoniel Parish, we have in either case a distance of eleven miles. But perhaps the fact that there are houses at different ends of the parish separated by a journey of sixteen miles will give a better idea of its size. The Ecclesiastical Parish of Glenavy includes the Civil Parishes of Glenavy, Camlin, and Killead, and the greater part of the Civil Parish of Ballinderry. This extensive parish contains two Catholic churches – one at Glenavy and the other at Aldergrove – and has at present a Catholic population of 1,850.

II. – IN THE LEGENDARY PAST.

The Territory of the Cruithni.

The Parish of Glenavy is rich in legendary and historical associations. The ancient name of the territory lying along Lough Neagh and stretching from Larne to Magheralin was The Country of the Cruithni (Cnoc na Cruitne), or of the Irish Picts.* The earliest inhabitants of this territory of whom we have any record are described in the Book of Lecan as the race of Conall Cearnach. They claimed descent, therefore, from one of the noblest of the Red Branch Knights, Conall the Victorious (Conaill Cearnach). The old Irish genealogies trace their descent back to another of the Red Branch Knights, Keltar, who lived near Downpatrick, at a place still called Rath Keltair ; they tell us that Neim, the daughter of Keltar, was the wife of Ailinn, son of Conall Cearnach. These Red Branch Knights, according to the ancient legends, were the great warriors of the North about the time of Christ. Their King, who ruled the Province of Ulster, was Conor Mac Nessa, and his residence was the famous Palace of Emania. Navan Fort, about two miles outside the city of Armagh, still marks the place where the palace stood. In all the wars that Conor Mac Nessa waged against Queen Maeve of Connacht and the other provinces, Conall Cearnach, Leary, Keltar, and the mighty hero Cuchullain were ever foremost in the fray. And when the enemies of the Ulster King were beaten off and peace restored, the victorious chieftains would return home each to his own stronghold, and there they led a gay and enterprising life. Now they would feast and revel with their retainers, and the banquet-hall would ring with merry song and boisterous laughter. Again they would ride forth with wavy crest and glittering spear to hunt the wild boar over mountain, wood, and glen. Such was the life of chieftain and warrior in those far-off days in Heroic Ireland, when Patrick had not yet set foot on Irish soil, nor had the light of Christianity come to dispel the gloomy clouds of Paganism : for Paganism, with all its careless., joy and revel, left the minds of thoughtful men a prey to-dread anxiety as to the unseen world to come.

stretching from Larne to Magheralin was The Country of the Cruithni (Cnoc na Cruitne), or of the Irish Picts.* The earliest inhabitants of this territory of whom we have any record are described in the Book of Lecan as the race of Conall Cearnach. They claimed descent, therefore, from one of the noblest of the Red Branch Knights, Conall the Victorious (Conaill Cearnach). The old Irish genealogies trace their descent back to another of the Red Branch Knights, Keltar, who lived near Downpatrick, at a place still called Rath Keltair ; they tell us that Neim, the daughter of Keltar, was the wife of Ailinn, son of Conall Cearnach. These Red Branch Knights, according to the ancient legends, were the great warriors of the North about the time of Christ. Their King, who ruled the Province of Ulster, was Conor Mac Nessa, and his residence was the famous Palace of Emania. Navan Fort, about two miles outside the city of Armagh, still marks the place where the palace stood. In all the wars that Conor Mac Nessa waged against Queen Maeve of Connacht and the other provinces, Conall Cearnach, Leary, Keltar, and the mighty hero Cuchullain were ever foremost in the fray. And when the enemies of the Ulster King were beaten off and peace restored, the victorious chieftains would return home each to his own stronghold, and there they led a gay and enterprising life. Now they would feast and revel with their retainers, and the banquet-hall would ring with merry song and boisterous laughter. Again they would ride forth with wavy crest and glittering spear to hunt the wild boar over mountain, wood, and glen. Such was the life of chieftain and warrior in those far-off days in Heroic Ireland, when Patrick had not yet set foot on Irish soil, nor had the light of Christianity come to dispel the gloomy clouds of Paganism : for Paganism, with all its careless., joy and revel, left the minds of thoughtful men a prey to-dread anxiety as to the unseen world to come.

* The word Cruit is supposed to mean “colour,” and hence ” Picti ” or “Pictores,” would be the Latin equivalent of Cruitne

The Civil Parish of Glenavy lay within the boundaries of the ancient Dalmunia. (Dal mBuinne= the race of Buinne, son of Fergus Mac Roy). This gives it another link with the legendary past. The territory of Dalmunia, or, as it is sometimes called, Dalboyn, included also Kilultagh, Kilwarlin, Hillsborough, and Lisburn, and was peopled by the race of Fergus Mac Roy. Fergus was King of Ulster about the beginning of the first century, .A. D. He wished to marry the beautiful widow Ness. She would not give her consent unless on the understanding that her son Conor, then a mere boy, should be allowed to be king for a year. To this Fergus, with the consent of the nobles, agreed. When the year was up, the queen-mother had guided her son so wisely in the use of his power that the nobles now refused to supersede Conor. This is what the mother had anticipated. And so Conor Mac Nessa remained King of Ulster Fergus Mac Roy acquiesced in the situation, and became chief-counsellor of Conor and tutor of the infant-hero Cuchullain. Some years later, when war broke out between Conor and Maeve of Connacht, we find Fergus as chief-counsellor of Queen Maeve. He had abandoned the service of Conor, and not without good reason. Naoise, one of the nobles, had eloped with Deirdre, the most beautiful of the women of Erin, who was destined to be the wife of King Conor himself. “Therefore, accompanied by Deirdre and his own two brothers, Ainle and ,Ardan, the sons of Ushna, he fled from the anger of Conor into Scotland. They remained in exile many years, and Conor and Fergus pledged their word of honour that, if they returned home again, they would be unharmed. Deirdre had a foreboding of evil, but the sons of Ushna calmed her fears, and they all returned home. In spite of the royal guarantee, however, they were foully put to death. Fergus Mac Roy could not brook to be a party to such treachery, and it was for this reason he abandoned the Ulster King and took service with Maeve of Connacht.

These are but specimens of the numerous legends that group themselves around the ancient inhabitants of Antrim, Down, and Armagh. No one to-day would venture to put them down as serious history. But the folk-lore of a people cannot be utterly discarded. The stories of the ancient heroes reveal the ideals of a remote antiquity, and the events described must have been founded on real deeds of heroism that were exaggerated and glorified as they were told and retold round the hearth to each succeeding generation.

To be continued