The ‘Tyninghame’ copy of the “Declaration” from 1320 AD

Alongside the battles and bloodshed of the Scottish “Wars of Independence” in north Britain there was also a diplomatic struggle – a war of words and propaganda. The two Norman warlords the “Scottish” Robert the Bruce and the “English” Edward II vied for the support of the Pope, who had confirmed Edward’s feudal Lordship over the Norman Barons in Scotland.

On 10 February 1306 Robert the Bruce and John the Red Comyn, lord of Badenoch, met at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries, resulting in the murder before the altar of Comyn by Bruce. The subjugation of Buchan, which then took place in 1308, saw vast areas of Buchan in northeast Scotland, then ruled by Clan Comyn, burned to the ground by Bruce and his ruthless brother Edward, immediately following their May 1308 success at the Battle of Barra.

After his defeat at Barra, John Comyn, Earl of Buchan fled to England. Bruce’s men chased him as far as Turrif, a distance of sixteen miles (25 km). Before heading south to lay siege to Aberdeen Castle, the Bruces “destroyed by fire his whole Earldom”, including all the castles and strongholds, principally Rattray Castle and Dunarg Castle.

Bruce’s men then proceeded to kill all those loyal to the Comyns, men, women and children, in an orgy of ethnic cleansing, which was to haunt Bruce on his deathbed, destroying their homes, farms, crops and slaughtering their cattle. Terrorising the locals, Bruce prevented any possible chance of future hostility towards him and his men. The Comyns had ruled Buchan for nearly a century, from 1214, when William Comyn inherited the title from his wife. Such was the terror and destruction, however, that the people of Buchan lost all loyalties to the Comyns and never again rose against Bruce’s supporters.

The Pope was a powerful figure in medieval times. Bruce’s killing of Comyn (Cummings) on holy ground at Greyfriars Kirk led to his excommunication. The Pope had turned his back on Bruce – so that in 1318 Bruce, his lieutenants and his bishops were all excommunicated.

Bruce reacted by having three letters sent to the Pope. The first was a letter from Robert himself, the second from his lackeys, the Scots clergy, and the third from the nobles of Scotland. The third letter became known as the “Declaration of Arbroath” and survives to this day, being used by modern Scottish Nationalists for political purposes.

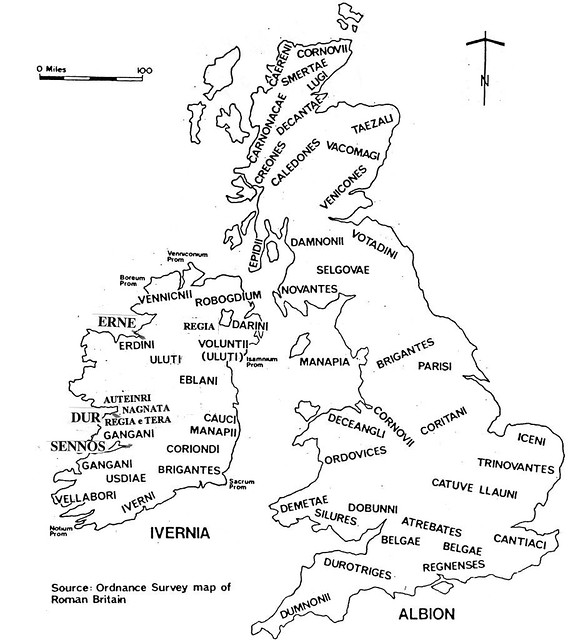

In this letter, the Scots, who claimed descent from Irish invader warlords, vaunted their expulsion of the native Britons and their utter destruction of the Picts, neither of which they were actually able to achieve, for we are the descendants of these ancient peoples. Their claim of one hundred and thirty Kings is pure fabrication and most of the second paragraph is nonsense. The relics of St Andrew were probably brought to Britain in 597 as part of the Augustine Mission, and then in 732 to Fife, by Bishop Acca of Hexham, a well-known collector of religious relics.

This translation of the original Latin was compiled by Alan Borthwick in June 2005

To the most Holy Father and Lord in Christ, the Lord John, by divine providence Supreme Pontiff of the Holy Roman and Universal Church, his humble and devout sons Duncan, Earl of Fife, Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, Lord of Man and of Annandale, Patrick Dunbar, Earl of March, Malise, Earl of Strathearn, Malcolm, Earl of Lennox, William, Earl of Ross, Magnus, Earl of Caithness and Orkney, and William, Earl of Sutherland; Walter, Steward of Scotland, William Soules, Butler of Scotland, James, Lord of Douglas, Roger Mowbray, David, Lord of Brechin, David Graham, Ingram Umfraville, John Menteith, guardian of the earldom of Menteith, Alexander Fraser, Gilbert Hay, Constable of Scotland, Robert Keith, Marischal of Scotland, Henry Sinclair, John Graham, David Lindsay, William Oliphant, Patrick Graham, John Fenton, William Abernethy, David Wemyss, William Mushet, Fergus of Ardrossan, Eustace Maxwell, William Ramsay, William Mowat, Alan Murray, Donald Campbell, John Cameron, Reginald Cheyne, Alexander Seton, Andrew Leslie and Alexander Straiton, and the other barons and freeholders and the whole community of the realm of Scotland send all manner of filial reverence, with devout kisses of his blessed feet.

Most Holy Father and Lord, we know and from the chronicles and books of the ancients we find that among other famous nations our own, the Scots, has been graced with widespread renown. They journeyed from Greater Scythia by way of the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Pillars of Hercules, and dwelt for a long course of time in Spain among the most savage tribes, but nowhere could they be subdued by any race, however barbarous. Thence they came, twelve hundred years after the people of Israel crossed the Red Sea, to their home in the west where they still live today. The Britons they first drove out, the Picts they utterly destroyed, and, even though very often assailed by the Norwegians, the Danes and the English, they took possession of that home with many victories and untold efforts; and, as the historians of old time bear witness, they have held it free of all bondage ever since. In their kingdom there have reigned one hundred and thirteen kings of their own royal stock, the line unbroken a single foreigner. The high qualities and deserts of these people, were they not otherwise manifest, gain glory enough from this: that the King of kings and Lord of lords, our Lord Jesus Christ, after His Passion and Resurrection, called them, even though settled in the uttermost parts of the earth, almost the first to His most holy faith. Nor would He have them confirmed in that faith by merely anyone but by the first of His Apostles — by calling, though second or third in rank — the most gentle Saint Andrew, the Blessed Peter’s brother, and desired him to keep them under his protection as their patron forever.

The Most Holy Fathers your predecessors gave careful heed to these things and bestowed many favours and numerous privileges on this same kingdom and people, as being the special charge of the Blessed Peter’s brother. Thus our nation under their protection did indeed live in freedom and peace up to the time when that mighty prince the King of the English, Edward, the father of the one who reigns today, when our kingdom had no head and our people harboured no malice or treachery and were then unused to wars or invasions, came in the guise of a friend and ally to harass them as an enemy. The deeds of cruelty, massacre, violence, pillage, arson, imprisoning prelates, burning down monasteries, robbing and killing monks and nuns, and yet other outrages without number which he committed against our people, sparing neither age nor sex, religion nor rank, no one could describe nor fully imagine unless he had seen them with his own eyes.

But from these countless evils we have been set free, by the help of Him Who though He afflicts yet heals and restores, by our most tireless Prince, King and Lord, the Lord Robert. He, that his people and his heritage might be delivered out of the hands of our enemies, met toil and fatigue, hunger and peril, like another Macabaeus or Joshua and bore them cheerfully. Him, too, divine providence, his right of succession according to or laws and customs which we shall maintain to the death, and the due consent and assent of us all have made our Prince and King. To him, as to the man by whom salvation has been wrought unto our people, we are bound both by law and by his merits that our freedom may be still maintained, and by him, come what may, we mean to stand. Yet if he should give up what he has begun, and agree to make us or our kingdom subject to the King of England or the English, we should exert ourselves at once to drive him out as our enemy and a subverter of his own rights and ours, and make some other man who was well able to defend us our King; for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom — for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

Therefore it is, Reverend Father and Lord, that we beseech your Holiness with our most earnest prayers and suppliant hearts, inasmuch as you will in your sincerity and goodness consider all this, that, since with Him Whose vice-gerent on earth you are there is neither weighing nor distinction of Jew and Greek, Scotsman or Englishman, you will look with the eyes of a father on the troubles and privation brought by the English upon us and upon the Church of God. May it please you to admonish and exhort the King of the English, who ought to be satisfied with what belongs to him since England used once to be enough for seven kings or more, to leave us Scots in peace, who live in this poor little Scotland, beyond which there is no dwelling-place at all, and covet nothing but our own. We are sincerely willing to do anything for him, having regard to our condition, that we can, to win peace for ourselves. This truly concerns you, Holy Father, since you see the savagery of the heathen raging against the Christians, as the sins of Christians have indeed deserved, and the frontiers of Christendom being pressed inward every day; and how much it will tarnish your Holiness’s memory if (which God forbid) the Church suffers eclipse or scandal in any branch of it during your time, you must perceive. Then rouse the Christian princes who for false reasons pretend that they cannot go to help of the Holy Land because of wars they have on hand with their neighbours. The real reason that prevents them is that in making war on their smaller neighbours they find quicker profit and weaker resistance. But how cheerfully our Lord the King and we too would go there if the King of the English would leave us in peace, He from Whom nothing is hidden well knows; and we profess and declare it to you as the Vicar of Christ and to all Christendom. But if your Holiness puts too much faith in the tales the English tell and will not give sincere belief to all this, nor refrain from favouring them to our prejudice, then the slaughter of bodies, the perdition of souls, and all the other misfortunes that will follow, inflicted by them on us and by us on them, will, we believe, be surely laid by the Most High to your charge.

To conclude, we are and shall ever be, as far as duty calls us, ready to do your will in all things, as obedient sons to you as His Vicar; and to Him as the Supreme King and Judge we commit the maintenance of our cause, casting our cares upon Him and firmly trusting that He will inspire us with courage and bring our enemies to nought. May the Most High preserve you to his Holy Church in holiness and health and grant you length of days.

Given at the monastery of Arbroath in Scotland on the sixth day of the month of April in the year of grace thirteen hundred and twenty and the fifteenth year of the reign of our King aforesaid.