The Irish News

Tuesday, July 23, 1985

North’s sickness blamed on famine

‘Plantation not cause”

When two local magazines carried articles on Belfast publishing, Blackstaff and Appletree got full attention. But another publisher – with nearly a dozen recent titles to its credit – was excluded.

The Pariah is Pretani.

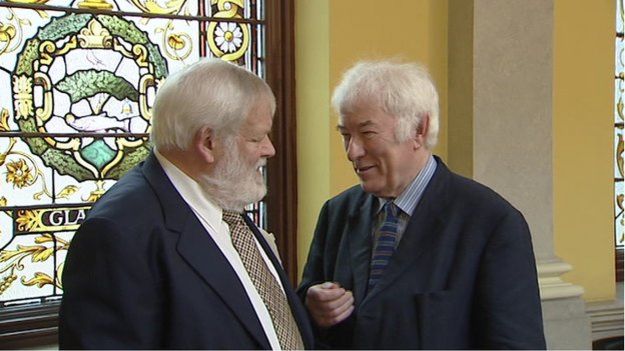

It is the creation of local historian Ian Adamson. He is a demure intellectual, a quiet and methodical wee man with a habit of sitting low and looking up at you. He doesn’t strike you as assertive, yet he has the push to write and publish while working at the same time as a doctor. He doesn’t look ambitious – whatever an ambitious man looks like – yet he has taken a mission on himself, a mission a mission to work for a reassessment of the history of Ulster, believing this would counteract sectarianism.

“Roman Catholics feel that Ulster is not their word anymore. They don’t like to use it, but they have a real sense of the Ulster tradition. The Protestants use the word, but they have no sense of the tradition.”

That’s an example of how aphoristic he can be, although just as his sentences evaporate into unmanageable syntax as he diverges here and there to make his point fair and complete.

But he is never hard to understand and he is full of unsettling historical facts,

He notes, for instance, that those who insist on not calling Northern Ireland Ulster on the grounds that the real Ulster has nine counties, are adhering to a system established by the Elizabethan English administration – a strange stand for a republican to take.

The real Ulster, he argues, was a stable settlement, with a fluid boundary, in this part of Ireland and mingling with the rest of Scotland, with which it was linked to rather than separated from the sea for thousands of years.

He doesn’t pretend that the plantation of Ulster by the Scots in the seventeenth century was a good thing. But he insists that it was more a case of people moving from one part of their region to another.

“In Irish terms, where people and their make-up are so important, it is vital to state there was no difference between the native Ulster people and the planters. They shared a difference from the English.”

That difference was one of language – both spoke Gaelic and were to develop a single dialect of English – and a difference of culture in that both belonged to a race which has a ‘sense of the unseen world’.

“The two communities here think they are different from each other. That’s not true, and, in terms of Ulster identity or nationality, or whatever you call it, it’s terribly sad that a people who must be considered one of the oldest settled people in Western Europe should lose out on this ancientness through petty quarrels”.

In his recent book, The Identity of Ulster, Adamson traced the Ulster history back to pre-Celtic times to the Cruthin people, through several shifts of population between Ireland and Scotland. He followed the movement of the Scots Irish to the New World where they played a major part in the destruction of the Red Indians and the defence of the Alamo.

And he has more disturbing historical facts – disturbing for anyone who thought the whole thing was simple.

“At the time of the plantation settlement, you had your man Owen Roe O’Neill, who thought of himself as Ulster – Ulster Catholic granted – and the feeling of Ulster, as such, was extremely important to him.

“There were other Roman Catholics. There were Catholic Anglo-Irish and there were Catholic Southern Irish, but there was something about this man which didn’t allow him to get into that whole situation in the South, didn’t allow him to contribute as much to the Confederation of Kilkenny, when that would have decisively changed the course of Irish history in favour of the Irish.

What was wrong with him was that he still thought he was Ulster. That’s what wrecked the whole thing and led eventually to the main Scottish settlement of Ireland following the Williamite War”

Adamson’s books have had some influence, Andy Tyrie said recently that the UDA used one of Adamson’s books to gen up their men in prison on how to counter accusations from republicans that they were interlopers in Ireland. In the same article, Tyrie said he would like to learn to speak Ulster Gaelic as part of his heritage.

Adamson does not want to be thought of as a Protestant or loyalist historian. Although he has been described as these things. Nor is he the Von Daniken of the Crumlin Road. His research has been extensive and has won the respect of scholars here and abroad. Tom Paulin wrote: “Adamson’s learning and generous humanity are very impressive. His reverence for art and culture…are everywhere evident in his work.”

Trying to remind young Protestants of their ancient tradition, he has been taking groups to see French monasteries which had connections with Bangor in early Christian times. He has written a book about Bangor’s influence on the rest of Europe. He notes that the word Shankill means “old church’ and refers to a church established by the Bangor monastery.

If the Plantation of Ulster was not the source of sectarianism here, what was the source? Adamson traces it to the Famine:

“I think before the Famine, the Churches in Ireland had their influence, but underneath it, there was a relic of the pagan past right throughout the countryside. Respect for the land and influences over the land – the fairies – was quite strong among Protestants and Catholics alike.

But after the Famine, when the whole place was devastated really by pestilence and disease, the belief or reliance on the little people was virtually brought to a standstill. It was a faith shattered – and that allowed the growth of a more fundamentalist position within the Protestant Church and the growth of a strict tradition in the Catholic Church, turning more to Rome.”

In short, the differences between Catholic and Protestants only became really significant when, after the Famine trauma, both turned to the basic rules of their religions.

Describing the Protestant faith, he says “There is a fundamental belief, within the Protestant heart, that they are following the path of Israel, and that they have become a new Jewish race in the modern world.”

Some critics of Adamson, in fact, say his understanding of the Plantation as a return to an ancient homeland is an appeal to that sentiment. He denies there is any real parallel. The Israelites were, supposedly, given a land to conquer; there is no way Adamson’s other writings would support a Protestant supremacy in Ulster.

He thinks that; by reminding people of their common cultural background, he will help to overcome the differences between them, I put it to him that it may be too late to do this if the force of institutional religion is now stronger than the real Ulster heritage.

“I don’t think institutional religion will stand up to the future really.”

Would he then see a coming together of the two communities in Ulster as involving a breakdown of the influences of institutional religion.

“Yeah,” he said very meekly, although it was his own reasoning that led to the question.

“You would like to see such a breakdown?” I ask.

“Yes”

But then, he never doubted there was a long way to go.

MALACHI O’DOHERTY

!["Many congratulations to the poet Michael Longley, who last night received the Freedom of Belfast. @[109992386995:274:Culture Northern Ireland] has a vast archive of original content charting his extraordinary career, from Q&A interviews to videos and reviews: http://ow.ly/KIDxK </p>

<p>Help us to safeguard and grow that archive for future generations by supporting the #SaveCultureNI campaign: http://ow.ly/KIDOY"](https://scontent-cdg.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xpa1/v/t1.0-9/s526x395/12485_10153522910811996_5054415960755095291_n.jpg?oh=c87ad0c0e6d8f8ef8915392ddb1059df&oe=557B146E)