It is now about 10 years since I last spoke in this historic ampitheatre of l’Institut du Monde Anglophone, 5, rue de l’École de Médecine of the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3, where Jean-Paul Marat once lay in state. My talk centred on cultural politics in Northern Ireland, particularly on the issues of Ulster Scots and Irish Gaelic. Since then my work has been taken up and expanded, as you have heard, by Helen Brooker in a community movement based on Common Identity. I would therefore like to pay tribute to her team at Pretani Associates, David Brooker, Jill Lyttle and Heather Knipe for their encouragement and support.

It is now about 10 years since I last spoke in this historic ampitheatre of l’Institut du Monde Anglophone, 5, rue de l’École de Médecine of the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3, where Jean-Paul Marat once lay in state. My talk centred on cultural politics in Northern Ireland, particularly on the issues of Ulster Scots and Irish Gaelic. Since then my work has been taken up and expanded, as you have heard, by Helen Brooker in a community movement based on Common Identity. I would therefore like to pay tribute to her team at Pretani Associates, David Brooker, Jill Lyttle and Heather Knipe for their encouragement and support.

Jean-Paul Marat. (24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793)

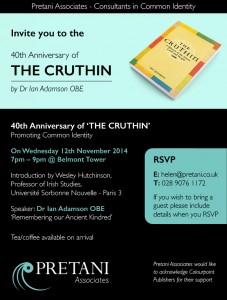

My own journey to this room began in a letter to me dated 5th June, 1975, from what was then the U.E.R. des Pays Anglophones of the Université de Paris III-Sorbonne Nouvelle. Professor René Fréchet thanked me for my book, The Cruthin, which had been published the previous year. This initial contact was to be the beginning of a long and productive correspondence between Professor Fréchet and myself, a liaison which lasted until his death in 1992.

In his obituary, Mark Mortimer, who had taught at the British Institute in Paris for some thirty years, was to say that René Fréchet was for many years the voice of Ireland in Paris. I was greatly honoured that Professor Fréchet should take an interest in my work. Commenting on my Identity of Ulster, published under my own imprint, Pretani Press in 1982. he was to write:

“What an interesting, curious piece of work this is. Generally, if we are told it is not a question of a war of religion in Ulster, we are told about opposition between Catholics, whom people think of as mostly wishing for the unification of the island, and Protestants who want to remain British.

Adamson however, does not militate in favour of the bringing together of two quite distinct communities. He says that their division is artificial, that they are all more or less descendants of pre-Celtic peoples, and in particular of the Cruthin, who were constantly moving backwards and forwards between Ulster and Scotland, where they were called Picts, a fact that did not prevent their homeland becoming the most Gaelic part of Ireland. “British”, as far as he is concerned, takes on a meaning that Ulster people tend to forget.

Here are some interesting phrases for comparison. “Old British” was displaced in Ireland by Gaelic just as English displaced Gaelic”; “the people of the Shankill Road speak an English which is almost a literal translation of Gaelic”; “the majority of Scottish Gaelic speakers are Protestants”. In fact the author is especially interested in Protestants, but those Protestants who have worked or are working towards reconciliation (could these even be the United Irishmen of the 1790’s), for a co-operative movement, for a kind of popular autonomy or self-management. He shows the paradoxical confusion of antagonistic, partly mythical traditions, and is trying to convince people of the fundamental unity of Ulster”.

In the chapter The Language of Ulster in this book, I set out my vision for the future of our several languages and their variants, as part of an attempt to foster a common identity in Ulster to take our people beyond the religious divide. Little did I realise the extent of hostility this would engender, not among the ordinary people, but by a section of the academic establishment in Northern Ireland .

In 1991, I published The Ulster People under my Pretani Press imprint. Professor Frechet wished to translate it into French but his death the following year prevented that, and the fact that some Irish academics wanted to burn it dissuaded me from bringing out a second edition. Twenty years later, on January 27th, 2011, Holocaust Memorial Day, I visited the Exhibition on the Millisle Jewish Refugees in the North Down Museum and was geatly moved by it. I wrote a comment in the book of comments provided by Sandra Baillie. Sandra has written in Presbyterians in Ireland about the “Cruithin Myth” and the fact that ” this story has not been taken very seriously by academics or the general public”, so some explanation is obviously needed.

The name Cruthin is the Gaelic equivalent of the original word Pretani, so let us look for a minute or two at whom they were.The Greeks have an ancient history of settlement in the area of land now known as France. They established a colony in Massalia, known today as Marseille in the South of France. Massalia became one of the major trading ports and was at its height in 400 BCE. The most famous citizen of Massalia was the mathematician, astronomer and navigator Pytheas. Between 300 and 330 BCE Pytheas organized an expedition by ship into the Atlantic taking him past the British islands as far as Iceland, Shetland and Norway, where he was the first scientist to describe drift ice and the midnight sun. In his Concerning the Ocean, he gave the earliest reference to these islands, calling them the Isles of Pretani (Pretanikai nesoi) a name the people used for themselves, the meaning of which will never be known.

These names had come to the general knowledge of Greek Geographers such as Erathosthenes by the middle of the third century BC. Together they were known to the Greeks via their allies the Celts as the Pretanic Islands or Islands of the Pretani. Between 60 – 30 BCE Diodorus Siculus, a Sicilian, who was a Greek historian and geographer wrote Bibliotheca historica. Within this book he has recorded the name the Isles of Pretani. Around 50 BC Diodorus wrote about “those of the Pretani who inhabit the country called Iris (Ireland). Thus the Pretani are the most ancient inhabitants of the British Isles to whom a definite name can be given and Pretania or The Isles of Pretani are the first known names of the islands now known as the British Isles.

Following the Greeks, the Roman Republic had long relied for its strength upon a sound citizen body headed by an aristocratic Senate. From just before 100 BCE, the balance of power swung towards such successful generals as could control the now great empire. Julius Caesar was perhaps the greatest of these generals. He had out-generalled and defeated the fine soldier Pompey; shown more political acumen than the Senators; conquered Gaul and fought in Britain, Spain and North Africa, Greece and Anatolia to assert his predominance and become dictator. He then transformed the very basis of government throughout the empire.

The last phase of colonisation of Britain before the Roman conquest came with the Belgic settlements in the south east during the first century BCE. These Belgic colonies gave rise, according to Julius Caesar, to the different petty states of Britain the name of those from which they came. Caesar’s report was the first and only record from historical sources of Celtic or part Celtic migration to Britain. His famous Gallic Wars gives us a personal account of Gaul and the battles he fought there.

Caesar tells us that the Gaul of his day was divided into three parts, inhabited by three nations; Belgae, Celtae and Acquitani, all of whom different in language institutions and laws. Since the Romans knew all three as Gauls and the leaders and tribes at least have Celtic names, we may assume all were Celtic speaking though of different dialects and ethnic origins, the Belgae having strong Germanic elements. These Germanic elements made it relatively easy for the Belgae, the Fir Bolg of Irish Mythology, to be absorbed by the Franks in Europe and the Anglo Saxons in Great Britain.

Caesar limits the Celtae to that country included from north to south between the Seine and the Garonne and from the Ocean on the west to the Rhine in Helvetia, and the Rhone on the east. The Veneti were the most powerful of the Celtae and inhabited the country to the north of the mouth of the Loire, (Liger). We know that the Domnonii of Cornwall and Devon were the most cultivated of their British relatives and that the Veneti traded with them for the tin of Cornwall. The Domnonian Britons reserved the legend that they came from Glas-gwyn, from the country of the Liger. Migrating to Ireland under Roman pressure and displacing the aboriginal pre-Celtic Pretani or Cruthin, they called themselves Lagin or Domnainn, maintaining the tradition that they were originally from Armorica. When the Irish Lagin later invaded the Lleyn Peninsula in Wales later from Ireland it took the name of Guined (Gwynedd) which derives directly from Veneti.

The Belgae inhabited what is now north eastern France and the Low Countries. The tribe which never sued for peace from Caesar was the Manapii who were originally seated on the Meuse and on the Lower Rhine. This great tribe was to become known to the later Gaels as the Fir Manaig, Men of the Manapii , who gave their name to Fermanagh and Monaghan in Ireland, the Pretanic name of which was Erdinia. It is probable that they also inhabited the Isle of Man (Monapia) before the Gaelic conquest. It was the Manapii along with the Morini and other Northern tribes who maintained an independent Gaulish area following Caesar’s campaign of 57 BCE, when he massacred 50,000 Belgic warriors at the earliest recorded Battle on the Somme. In 56 BCE the Veneti threw off the yoke of Rome and the whole coast from the Loire to the Rhine joined the insurrection. Caesar attacked the powerful Venetian navy and destroyed it, selling the defeated captives into slavery to a man. And it was the help they received from their British relatives which prompted his invasion of Britain in 55 BCE.

The British invasion was to be a Pyrrhic victory for Caesar. In 54 BCE Ambiorix brought together an alliance of Belgic tribes, the Eburones, Manapii, Nervii and Atuatuci allied to local German tribes. He launched an attack on 9000 Roman troops under Sabinus and Cotta, Caesar’s favourite generals, at Tongres and wiped them out. Caesar retaliated quickly, determined to exterminate the Belgic confederacy which was ruthlessly ravaged in all-out genocide. Ambiorix however, was never captured and disappeared from the pages of Continental History, but the Eburones re-emerged in Britain as the Brigantes (Ui Bairrche) just as the Manapii (Managh) came to Ireland. Their last refuges were to be Newtownbreda and Taughmonagh in Belfast.

In 52 BCE the brilliant Belgic leader Commius of the Atrebates turned against his former ally Caesar. He led a large force to join the armies of his kinsman Vercingetorix against him in a great insurrection which was to change the course of European history. Following Vercingetorix’s defeat, Commius became over-leader of the Belgic Atrebates, Morini, Carnutes, Bituriges, Bellovaci and Eburones and many Belgae followed him to his British Kingdom in the last Celtic-speaking folk movement to Britain, rather than endure the savagery of Roman civilisation.

Coincidentally, Julius Caesar , following the example of the Gauls, changed the “p” in Pretani to “b” , giving us the term “Britannia” and the islands he invaded became the “Britannic Isles”, or, as we call them today, the “British Isles”, the larger island later becoming Great Britain and the smaller Little Britain. However the “p” has been retained in modern Welsh: ieithoedd Brythonaidd/Prydeinig, in Cornish: yethow brythonek/predennek, and in Breton: yezhoù predenek, so that the term Pretani has survived in common speech in both the United Kingdom and France. Indeed Prydain is still used on the British passport today.

In 1999 Wesley Hutchinson published his masterly study “ espaces de l’imaginaire unioniste nord-irlandais” which was the first serious scholarly treatise on the Cruthin or Pretani. It was published by the Groupe de rescherches irlandaises of the Universite de Caen and remains the only treatise of its kind. Neglect, if not downright induced ignorance, of the subject remains the order of the day. More recently however the Brittonic or Old British substrate underlying Gaelic placenames has received more attention in the work of Dr Paul Tempan of the Ulster Place names Project, Queen’s University, Belfast. Old British names are becoming increasingly apparent, most prominently in Antrim and Down, the core area of Old Ulidia. Examples are Braniel, Lambeg, Glenavy, Castlereagh, Tullycarnet, Ballymiscaw, which now constitutes the Stormont Estate, and Bangor in County Down, as well as the famous personal names of Padraig or Patrick and Brendan the Navigator. But there are also Brittonic elements throughout Ireland, for example, the term Gaoth which occurs in Gaoth Barra and Gaoth Dobhair (Gweedore) in Donegal, as well as Gaoth Sáile in Mayo.

Professor Hutchinson has also initiated study in linguistic preservation which I would term the Hutchinson Triads: English, Ulster Gaelic and Ulster Scots or Ullans in Northern Ireland; English, Irish Gaelic and Ulster Scots in the Republic of Ireland; and French, Breton and Occitan in France. To this I would add English, Scots and Scottish Gaelic in Scotland and English, Geordie and Cornish in England. Geordie, or Northumbrian English, is the parent of Scots and more conservative and closer to the language of the invading Angles than modern English. By a process known as “colonial shift”, Ullans is a purer form of Scots than that spoken in Scotland itself. Geordie is also the most conservative form of English and the works of the Venerable Bede, for example, are more easily translated into Geordie than Standard English. Welsh remains well ahead on its own

What are we to do about this neglect in general? Well, Agnotology is one answer. Agnotology is the study of culturally induced ignorance or doubt, particularly the publication of inaccurate or misleading scientific data. The neologism was coined by Robert N Proctor, a Stanford University professor specializing in the history of science and technology. Its name derives from the Neoclassical Greek word ἄγνωσις, agnōsis, “not knowing” (cf. Attic Greek ἄγνωτος “unknown”), and -λογία, –logia More generally, the term also highlights the increasingly common condition where more knowledge of a subject leaves one more uncertain than before. The BBC are a prime example in continuing to ignore the history of the Pretani.

A prime example of the deliberate production of ignorance cited by Proctor is the tobacco industry’s advertising campaign to manufacture doubt about cancer and other health effects of tobacco use. Under the banner of science, the industry produced research about everything except tobacco hazards to exploit public uncertainty. Agnotology also focuses on how and why diverse forms of knowledge do not “come to be”, or are ignored or delayed. For example, knowledge about plate tectonics was censored and delayed for at least a decade because some evidence was classified military information related to undersea warfare.

There are many causes of nescience or culturally induced ignorance. Paramount is the influence of the Mediacracy, or Main Stream Media, either through neglect or as a result of deliberate misrepresentation and manipulation. Corporations and governmental agencies can also contribute to nescience through secrecy and suppression of information, document destruction, and myriad forms of inherent or avoidable culturopolitical selectivity, inattention, and forgetfulness. It is therefore most appropriate that we are here today, in memory of Professor Fréchet, to explain the role of contemporary Irish nationalist academics in suppressing knowledge of the Pretani.

An emerging new scientific discipline that has connections to agnotology is Cognitronics. Cognitronics aims (a) at explicating the distortions in the perception of the world caused by the information society and globalization and (b) at coping with these distortions in different fields. Cognitronics means studying and looking for the ways of improving cognitive mechanisms of processing information and developing the emotional sphere of the personality – the ways aiming at compensating three mentioned shifts in the systems of values and, as an indirect consequence, for the ways of developing symbolic information processing skills of the learners, linguistic mechanisms, associative and reasoning abilities, broad mental outlook being important preconditions of successful work practically in every sphere of professional activity in information society.The field of cognitronics appears to be growing as international conferences have centred on the topic.

Equally important is the growth of knowledge within the community and Pretani Associates have promoted these ideas of Common Identity through a variety of Community organisations , such as the Ullans Academy, the Ballybeen Motivation Group, the Ulidia organization, the Dal Fiatach group and the Latharna group across Northern Ireland. But the largest and most informed to date has been the Dalaradia organisation based in what was the greatest Cruthin or Pretani Kingdom of Ireland, as was Caledonia in North Britain.. It is therefore a great pleasure to bring Robert Williamson, chairman of that organization, here to speak to you today about his own journey..