When I first began to write books on Ulster history in the late 1960s, it was in an attempt to fill the obvious vacuum which existed in general public awareness concerning the real roots of the people of Northern Ireland. The increasing violence and depressing communal tragedy which continued over two decades only highlighted the need to make available to Ulster’s divided community some very pertinent facts about their unseen, but very real, common history and heritage, their common identity. Little did I realise then that my own work would itself become part of the debate, gaining acceptance from all sections of the community, but at the same time coming under attack from those whose stereotyped views of Irish history were seriously disturbed by what was being revealed.

One of the main claims made against me was that I was “indulging in pure revisionism”. “Revisionism”, as the word implies, means to ‘revise’ one’s interpretation of history, though often the word is also used in a pejorative sense, implying that the revision is deliberately undertaken to help substantiate the revisionist’s own particular ‘slant’ on our past.

When The Cruthin was written, over forty years ago, such a charge of revisionism might have seemed to contain some validity. After all, terms and concepts such as ‘the Cruthin people’, ‘the non-Celtic Irish’, ‘the Galloway connection’, – appeared at that time to be confined mostly to my own work. Indeed, Michael Hall’s summation of my writings in Ulster – the Hidden History must have seemed so unfamiliar to the reviewer in the Linen Hall Review, that the latter concluded that the historical thesis being expounded aimed “at nothing less than an overthrow of current perceptions”.

To introduce something apparently so ‘new’ into the historical debate might, therefore, have served to confirm the ‘revisionist’ label. Yet before we come to such a conclusion, let us consider the following quotes:

“In the north (of Ireland) the people were Cruithni, or Picts… If the (Uí Néill) failed to subdue the south thoroughly, they succeeded in crushing the Ultonians (Ulstermen), and driving them ultimately into the south-eastern corner of the province. They plundered and burned Emain Macha, the ancient seat of the kings of the Ultonians, and made “sword land” of a large part of the kingdom… Consequent on the (Uí Néill) invasion of Ulster (was) an emigration of Irish Cruithin or Picts (to Scotland)… The men of the present Galloway were part of the tribe known in Ireland as Cruithni, that is Picts, and only differed from the Picts of (Scotland), in having come into Galloway from Ireland.”

To readers aware of the present controversy these quotes might appear to be a reasonable précis of some of my own writings. In fact, I am not the author of the quotes: they have been taken from the ninth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, published between 1876 and 1886 – over one hundred and thirty years ago. The Britannica’s historical interpretation was not an isolated one, however – many books of the period took a similar approach. With his deep interest in archaeology , the British Patriot Edward Carson orientated towards the “Pictish” or Pretanic origins of the British people, while, as an Ulster Scot, James Craig wrote about Dalriada…As a boy my father bought for me The Pictish Nation, its people and its Church by Archibald B. Scott published in September 1918 by T. N. Foulis of Edinburgh and London, Boston, Australasia, Cape Colony and Toronto. It was printed in Scotland by R & R Clarke Limited of Edinburgh. The author dedicated his book to his father and mother and to the memory of his youngest brother who died, in 1916, of wounds inflicted in action and sleeps in France with other comrades of the 1st Cameron Highlanders.This wonderful book was my introduction to the Picts.

The Pretani

In 1919 the eminent Irish Nationalist historian Eoin MacNeill, author of The Pretanic Background of Britain and Ireland , wrote: “When Ireland emerges into the full light of written history, we find the Picts a very powerful people in east Ulster… In Ulster, the ruling or dominant population of a large belt of territory, extending from Carlingford Lough to the mouth of the Bann, is named in the Annals both by the Latin name Picti, and its Irish equivalent Cruithni. They continue to be so named until the eighth century, when apparently their Pictish identity ceased to find favour among themselves.” MacNeill was co-founder of the Gaelic League and in 1913 he established the Irish Volunteers and served as their Chief-of-Staff. He held this position at the outbreak of the Easter Rising but had no role in it or its planning, which was carried out by Irish Republican Brotherhood infiltrators, so he was hardly a “Unionist ideologue” like myself,

Bishop McCarthy, in his edition of Adomnán’s Life of St Columba also wrote that “no fact in the pagan history of Ireland is more certain than that the whole country was originally held by the Irish Picts.” And contemporary thinking in Northern Ireland was summed up by H C Lawlor, who wrote in a publication for the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society in 1925:

“In those early times, when the history of Ireland begins to emerge from absolute obscurity or mythology, we find the country divided into five distinct Kingdoms, of which the Northern was known as Coiced Uloth or Cuigeadh Uladh, meaning the Fifth of the Uluti. This district was larger than the nine counties now called Ulster, and the indigenous inhabitants appear to have been a race variously called the Qreteni or Cruithni, but more familiarly known as the Irish Picts.

About the fourth century BC or earlier, a new race appears to have come to Ireland, commonly known as the Celts or Gaels; whence they came is uncertain. From ancient mythology and other sources it appears that they were a race of yellow-haired big-bodied people, contrasting in these respects with the aborigines. They came as conquerors; they appear to have landed in Ireland on the south-east coast, gradually pushing their way north and west, eventually establishing their chief and central headquarters at Tara in County Meath. That they drove the aborigines before them as one would drive herds of sheep is inconceivable; they conquered them and became the ruling class, holding the natives under them as serfs; they were apparently a small minority of the population.”

Irish traditions amply confirm the evidence of Greek writers that Ireland was once a country of the Pretani, Cruithin, or Picts. Our own writers, in the seventh century and later, show that in their time there were numerous families, including many of high degree, in every quarter of Ireland but especially in Ulster and Connacht, who were recognised to be of Pictish descent. The problem ‘Who were the Picts?’ has long been under discussion. Ancient and firm tradition, in Britain as well as in Ireland, declared them to be quite a distinct people from the Gaels and the Britons; and some who have sought to solve the problem have ignored the existence of a large Pictish element in Ireland. The view of the late Sir John Rhys appears most reasonable, that, whereas the Celts came from Mid-Europe and belonged to the ‘Indo-European’ linguistic group, the Picts belong to the older peoples of Western Europe. They were the chief people of Ireland in the Bronze Age, and to them the Irish arts and crafts and monuments of that age may be ascribed.”

The Cruthin

While I have clarified and amended such historical interpretations, having taken into consideration more recent archæological and historical conclusions, the direction of my enquiry is in fundamentally the same vein. Yet in the second half of the 20th century there occurred among the academic establishment a definite change in emphasis. The Irish somehow came to be considered as most definitely “Celts”, and references to pre-Celtic population groups such as the Cruthin were unaccountably deleted from most history publications. Even the present (dare I say ‘revised’) edition of the Britannica, in its section on Irish history, no longer makes mention of the Cruthin or even the ‘Galloway connection’.

Indeed, when we look closely at much of the academic material brought out over this period, it would appear that extensive ‘revision’ has indeed taken place, a revision which played down these former pre-Celtic and British aspects. It is ironic, then, that if the charge of revisionism can be substantiated, it is not with relation to The Cruthin, but to what has been taking place since the middle of the last century among the urban elite, who have indulged in a process of selective historical awareness.

Yet, even though nationalist propaganda does continue at a high level, when we come to look at what has been written by a few eminent academics in the past few years, including Brian Lacey and Tom O Connor, a remarkable – and for some, no doubt, uncomfortable – about-face seems to be occurring. Increasingly, historical evaluation is returning to some of that earlier thinking, with many previous misinterpretations having been corrected, of course – and it is the more-recent history that has been found ‘wanting’.

For example, an inter-disciplinary gathering of scholars a few years ago acknowledged that any Celtic ‘invasions’ into Ireland more than probably involved population groups numerically “far inferior to the native population”. Nowadays there is a growing acceptance that our predominant genetic heritage is not “Celtic” at all but can be traced back to the Neolithic period and before, with archæologist Peter Woodman concluding: “The Irish are essentially pre-Indo-European, they are not physically Celtic.” And of the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the North of Ireland, historian Francis Byrne has pointed out that, following the “Uí Néill” invasions into Ulster, “the bulk of the population in the reduced over-kingdom of Ulaid were the people known as Cruthin or Cruithni.”

While the prominent part played by Ireland’s pre-Celtic inhabitants within our historical and cultural heritage is slowly being acknowledged (or re-asserted), in some quarters such an admission is a non-starter. A well-known television presenter, appearing on the BBC (Northern Ireland) programme The Show, was quite adamant in his belief that the Irish were “all Celts”. And one prominent local academic, Richard Warner, who was formerly of the Ulster Museum, described recently by a fellow archaeologist as the “Rock Star” of Northern Irish archaeology, endeavoured to belittle the contribution the Cruthin have made to Ulster’s history. Speaking on the BBC Radio programme The Cruthin – A Common Culture? in July, 1989, he asserted that the Cruthin “are rather minor and they are rather unimportant and they made very little influence on Irish power or politics.” When we consider the contribution just one of these Cruthin made to not only Irish but European history, the abbot Comgall with his Bangor foundation, and the Cenel Conaill of ancient Venniconia (Donegal), this forthright assertion is astonishingly inaccurate.

And even if the Cruthin has thrown up no great historical personages such as Comgall or Congal Cláen, but had only become known to us as those ordinary people who had once formed the bulk of the Ulster population, then his assertion would still be pure élitist. For to claim that the majority of the population are “rather unimportant” indicates a strong bias against those who in real terms make up any people’s history – the Common People. It has also been said that some Loyalists have tried to use my work in their efforts to justify a sectarian position, in the hope that it might give a new credibility to the idea of a ‘Protestant Ascendancy’, only this time in cultural terms – a ‘we were here first’ mentality. How a proper reading of my work could lead to the supposition that the descendants of the Cruthin are somehow now exclusively Ulster Protestants is hard to fathom. Actually many individuals within the Protestant section of the community, including the Dalaradia organisation, are showing great interest in the Common Identity theme I have promoted for so many years and are not only feeling a new confidence in their Ulster identity, but have a desire to share this identity with the Roman Catholic section of the community.

Sectarian use of culture and history has never been one-sided, of course. Republicans and Nationalists have long been experts at this, only it has been accomplished with much more subtlety, is therefore less visible and has raised less comment. At times, however, Republican use of culture as a political weapon is explicit; as the Sinn Fein discussion booklet Learning Irish stated: “Now every phrase you learn is a bullet in a freedom struggle. Make no mistake about it, either you speak Irish or you speak English. Every minute you are speaking English you are contributing to the sum total of English culture/language in this island. There is no in between.” This ‘Irish’ language is supposed to be the heritage of all our people, yet when a group of young Nationalists were recently informed that over two dozen working-class Protestants had put their names down for a proposed class in Gaelic, they became most annoyed. Rather than being pleased to hear that the Protestant community was at last awakening to its ‘true’ heritage, their feeling was: “how dare they try to steal our language!”.

Yet at the same time, many individuals from the nationalist section of the community have readily admitted that the whole idea of a common identity has not only given them hope for the future, but has contributed more positively to their own historical appreciation than the dead weight of outdated and retrogressive Republican Nationalist ideology ever could.

Ironically, while protagonists in Northern Ireland still continue to argue over past history, their cultural heritage is even now being absorbed and enriched by new citizens coming from abroad, the latest coming from the West Indies, Africa, the Indian subcontinent, South-East Asia and Eastern Europe. And our lives have been continually enriched by the Jewish Community, whose contribution to our development has been so great. Reinforcement of our identity has also come from the large Ulster communities in the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Africa.

In many ways a cultural battle is now on, in which interpretations of history are right to the forefront. It is a battle in which narrow and exclusive interpretations, which served to consolidate each section of the community’s supposed hegemony of righteousness, are under attack from a much broader and inclusive interpretation of all the facets which go to make up our identity. A positive outcome of this battle might just help to drag the Ulster people away from their obsessions with distorted history and the divisive attitudes of the past. But what of the academic élite in all of this?

The Academic Suppression

“The darkest places in hell are reserved for those who maintain their neutrality in times of moral crisis” – Inferno: The Divine Comedy – Dante Alighieri

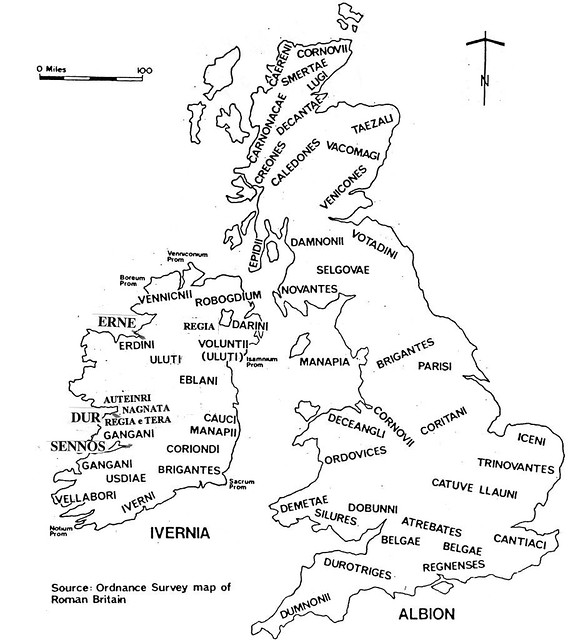

Ptolemy’s Map of the British Isles c150 AD.

A wonderfully arcane and self-contradictory article has appeared recently on the Internet. It is an unpublished paper by the English academic Alex Woolf (University of St Andrews) which he has given several times in different venues. It was originally written in about 2001 as a response to Ewen Campbell’s “Were the Scots Irish?‟ Antiquity 75 (2001), 285-92. Wolff spoke at at a Trinity College, Dublin Symposium (September 18/19th 2015) entitled “The Irish-Scottish World in the Middle Ages”. which I attended with my Pretani Associates colleague Helen Brooker. The Symposium was funded by The Ulster-Scots Agency, Trinity College and the Ministerial Advisory Group(MAG) Ulster-Scots Academy of the Department of Northern Ireland Culture , Arts and Leisure. It marked the 700th anniversary of the invasion of Ireland (1315 -1318) by the mass murderers, the Bruce brothers, Edward and Robert.

Woolf says that he had never got around to finally writing it up for publication and although he hoped he would eventually do so he could not see himself getting it done anytime soon. Various people working in the field, such as the Canadian historian and Picticist James E. Fraser, formerly in the University of Edinburgh, now back in the University of Guelph in Canada and the Irish-American Thomas Clancy, now in the University of Glasgow, had seen it in draft and responded to it so he felt he should put it into the public domain and therefore posted it on Academia.edu on 9th April 2012. It had not been significantly updated since 2005.

Campbell had assumed an obviously Scottish Nationalist approach to propose that Scottish Gaelic Dalriada came first and Irish Dalriada was formed from it and not the other way round. Woolf accepts this on what he says are linguistic grounds, even though he knows Campbell’s archæological evidence is untenable and his own conclusions are convoluted and even bizarre, so that, on the flimsiest of evidence, the hypothesis has now established itself in the academic canon. Frazer downplays the Cruthin in Ireland in his work on the Picts, although it clearly worries him to do so. Clancy is responsible for promoting the fallacy that St Ninian and St Uinniau (Finnian of Moville) are one and the same person. Yet Clancy stated at the Dublin Symposium that onomastic studies indicated that the Scottish Islands were not deeply Gaelic, thus indicating that Campbell’s thesis was nonsense.

Woolf’s article echoes the usual anti-intellectual and elitist approaches to my own work by politically motivated nationalistic “serious” academics, as my view that the Cruthin were the pre-Celtic inhabitants of these Islands, although they later spoke Gaelic (“Irish”) and Brittonic (“Welsh”), is completely misrepresented. And purposely so, to confuse and control the unwary. I have transcribed his words with emphasis in red on a most remarkable and telling admission, which explains everything.

“One of the most sensitive topics in the study of late prehistoric and early historical Ireland is that of the population group known as the Cruithin or Cruithni. Their name is the normal word used in medieval Irish for the Picts but it was also used for a group of túatha in the north of the country up until about AD 774. In origin this word is the Irish form of the British word for Britons, Pretani. In medieval Irish the Latin loan word Bretan was used for the Britons south of the Forth and Cruithni was reserved for the less Romanised peoples of the North who were termed Picti in Latin.

At one time some historians, including the great Eoin MacNeill, believed that the Pretani were the original inhabitants of both Britain and Ireland and that the Gaels had arrived at a late stage in prehistory displacing them from most of Ireland. According to this argument the Cruithni of northern Ireland were the last remnant of the pre-Gaelic inhabitants of the island. It has now become clear that this view is not supported by linguistic, historical or archaeological evidence. If British-speaking Celts ever did settle in Ireland they must have done so subsequently to the development, in situ, of the Gaelic language. Unfortunately the idea that Northern Ireland was British ab origine has proved attractive to certain elements within the Unionist tradition during the political troubles of that province. As a result „Cruithni Studies‟, to coin a phrase, have become the preserve of Unionist apologists such as Ian Adamson whose most recent book on the Cruithni concludes with a chapter on the Scots-Irish experience in the Appalachians.

Serious historians of early Ireland, tending as they do to have nationalist sympathies or to be politically neutral have tended, understandably, to steer clear of the topic. Jim Mallory is typical of most serious scholars when he summarises his brief discussion of the topic thus: “about the only thing the Cruthin hypothesis does emphasise are the continuous interactions between Ulster and Scotland. We might add that whatever their actual origins and ultimate fate, when the Cruthin emerge in our earliest texts they bear Irish names and there is not the slightest hint that they spoke anything other than Irish.”

This is nonsense, since Antrim and Down (Old Ulidia) and the rest of the island abound with Brittonic or Old British place names, which preceded Gaelic.

Wolff continues:

In typically provocative style Professor Dumville alluding to this kind of statement in his, so far unpublished, British Academy Rhŷs Lecture in Edinburgh a few years ago (1997?), asked what the evidence for such an assertion might be. I can only imagine that Dumville was questioning whether we had any texts of Cruthnian provenance and whether we could be certain that Gaelic writers, clearly able to Gaelicise Pictish personal and place names were not doing the same for the Irish Cruithni. Mallory is of course right that there is not the slightest hint that the Cruithni spoke anything other than Irish just as Dumville is correct, if I understood him, that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, but is this really all that can be said? St Patrick aside, contemporary literary witness in Ireland begins only in the course of the century between AD 550 and AD 650 and it is true that our sources, the chronicles and hagiography, give us only the name of the Cruithni, which appears periodically between 446 and 774, to suggest their foreignness.

At the beginning of the sixth century the western frontier of the Cruithni seems to have been in the neighbourhood of the Lough Foyle although by the 570s they had been pushed back beyond the river Bann by the northern Uí Néill. In the East the boundary of the Cruithni seems to have been somewhere in the region of Belfast Lough. Crudely speaking their territory at the dawn of history was equivalent to the modern day counties of Antrim and Londonderry. To the West were the Uí Néill, to the South the Airgialla and to the East the Ulaid. In the middle of this territory, pushed up between the Bush valley and the north coast lay the lands usually assigned to the Dál Riata in Ireland by modern scholarship. This enclave was entirely surrounded by Cruithni túatha .

Is it not odd that the most Irish people in Britain were, in their Irish territories, surrounded by those Irish people who were described by their countrymen as British? Can it be coincidence? The simplest explanation of this paradox would be to assume that, pace the later synthetic historians and genealogists the Dál Riata and Cruithni were in origin two parts of the same people, perhaps ultimately British in origin, who formed a political, cultural and linguistic bridge between the two islands.”

This is an incredibly poor piece of scholarship. Where is it “clear” that the Pretani presence throughout Ireland is not supported by linguistic, historical or archaeological evidence? Wolff seems to accept that “serious historians” of early Ireland to have “nationalist” sympathies but not “unionist” ones. For, certainly, the Englishman Richard “Indiana” Warner, with his Lost Crusade against the Cruthin, has stated publicly his sympathies are with the former. Warner and his colleague the Irish-American J P Mallory, formerly of the Queen’s University, Belfast, have spent years following their Quest for the Holy Gael. Their definition of the first “Irishman” remarkably is someone who spoke the “Irish” language, that is Gaelic, thus misusing the term “Irish“. He also chooses as “Irish” all the so-called descendants as a founding father Niall of the Nine Hostages and all his so-called descendants . The bulk of the population before this are relegated to the term “Irelander”.

Again this is incredibly poor scholarship. One would like to say that only an Englishman or an Irish-American could say this with a straight face. But no…Woolf says that “Jim Mallory is typical of most serious scholars”. Yet Mallory has written, referring to the archæeological approach to the subject of portable objects of the La Tène period in Ireland, burials and settlements that “we are appallingly ignorant of many other aspects of life in the Iron Age.” Woolf, by the way, amazingly leaves out the Iveagh Cruthin of Down to the south of Ulster as well as the Cenel Conaill to the west in his article, supporting the myth that the Cenel Conaill are “northern Ui Neill”. And by “British”, he means “from Great Britain”, since he seems to deny that epithet to “unionists” and the ancient Pretani people of Ireland, mesmerised as he is by the term “Irish”.

Actually the people of Scottish Dalriada were Gaelicised native Epidian Pretani and spoke Brittonic before Gaelic and non-Indo-European before that, as is demonstrated by the pre-Celtic name Islay. They were Gaelicised from Antrim by Gaelic speaking Robogdian Pretani in the Late Roman period by a process of commerce and conquest, as the Venerable Bede has stated. And they now speak Gaelic, Scots or, universally, English, though they remain, as they have always been, essentially Epidian Pretani, The truth is the truth and we are bound by it, as Professor Réne Fréchet of the Sorbonne University in Paris instructed me. Much of what I had written was new to him, and he was amazed and indeed apalled that he had never heard it before. He wanted to translate my work into French…the Irish academic elite wished to burn it. But their “politically neutral” counterparts, friends and colleagues in Great Britain did nothing and in doing so supported them. And they are the most reprehensible of them all. As Woolf and Frazer seem totally unaware that the Donegal Cenél Conaill of the so-called “northern Ui Neill” were actually Cruthin, although also completely Gaelicised in the Late Roman period, it is to the Venniconian Cruthin Kingdoms of Donegal that we will now turn.

The Venniconian Kingdoms.

The traditional understanding of the history of the Venniconian Kingdoms of Donegal maintained that at some time in the late fifth century the sons of Niall of the Nine hostages, Cairpre, Conaill, Enda and Eogan had launched an invasion into that territory from Tara, having defeated and conquered the indigenous people, or at least the rulers of those people. The four brothers were said to have divided out the territory of Donegal between them and each then established a kingdom which subsequently bore his name. In one form or another these kingdoms were believed to have lasted for all of the early mediæval period.

Collectively these kingdoms were never linked but are known to us now as the “Northern Ui Neill”, who went on to conquer the rest of western and central Ulster. Two of the kingdoms, Cenel Conaill and Cenel nEogan, were said to be the most dominant and for about three centuries after their establishment, the kingship of the whole territory was shared between them. In addition, when each of their kings was ascendant, they respectively claimed provenance of the prestigious kingship of Tara, which seems to have had some sort of overriding national influence. The ancient principality of Tír Eogain’s inheritance included the whole of the present counties of Tyrone and Londonderry, and the four baronies West Inishowen, East Inishowen, Raphoe North and Raphoe South in County Donegal.

As we now know, however, that story is a later propagandistic fiction, rather than a summary of what actually happened. Almost certainly it was given its classical form by and on behalf of the Cenel nEogan, during the reign in the mid eighth century of their powerful and ambitious king, Aed Allan, who died in the year 743. Whatever his actual victories and political successes, they were underlined by a set of deliberately created fictional historical texts which reported to give him and his ancestors a more glorious past than they had actually enjoyed. The same texts projected his dynasty back to the dawn of history and created a new political relationship with the neighbouring kingdoms. Whatever the initial reaction to them, these political fictions were plausible enough to endure and have been ultimately accepted as history by most commentators over the past thirteen hundred years. Aed’s pseudo-historians were probably led by the Armagh Bishop Congus, who exploited the opportunity provided by the alliance with the King to advance the case for the supremacy of his own church. Congus died in 750.

There appears to be no evidence that any of the rulers of the Venniconian Kingdoms of Donegal were related by blood to Niall of the Nine Hostages or to the Ui Neill. On the other hand it seems that there is evidence that Cenél Conaill were a Cruthin people associated in some way with the Ui Echach Coba and other east Ulster peoples. The Cenel nEogain, on the other hand, may well have had connections with the Dal Fiatach of maritime Down. The remarkable fact in all this is that of the groups said to have belonged to the Northern Ui Neill, Cenel Cairpre may have been the only genuine decendants of Niall of the Nine Hostages to have invaded South Donegal in the sixth century. And whatever evidence we have for the mid sixth century seems to show that it was the Cenel Conaill, rather than the Cenel nEogain, who were dominant among the Donegal Kingdoms at that time.

Conall Gulban , perhaps as Conall Cernach of the Ulster Cycle, is the figure most closely related to the ancestry of the Cenél Conaill. Whether he existed or not as an actual person, his name demonstrates a powerful political reality of some sort, in that he was definitely the ancestor of the fully historically attested Cruthin people of Ui Echach Coba of County Down, the Conaille Muirthemne of north Louth, the Sil nAedo of County Meath, and the Clann Cholmain of County Westmeath. The rise to power of what was said to have been Conall Gulban’s immediate descendants is equally something of a mystery. And among those descendants was our Colum Cille (Columba), the founder of the Monastery in Iona, where ironically in an Irish context the practice of keeping Annals and therefore the study of history seems to have been promoted.

We know almost nothing genuinely historical about Colum Cille’s early clerical life prior to his departure for Iona. On one occasion Adomnán writes that “this blessed boy’s foster-father a man of admirable life, the priest Cruithnechan” was apparently responsible for the child Colum Cille In view of the identification above that the saint’s people, the Cenél Conaill, actually belonged to the Cruthin, the priest’s name, which is a diminuative of that, may be very significant indeed.

The Tartessian Language.

The Tartessian language is the extinct Paleohispanic language of inscriptions in the Southwestern script found in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula mainly in the south of Portugal ( Algarve and southern Alentejo), but also in Spain (south of Extramadura and western Andalusia). There are 95 of these inscriptions with the longest having 82 readable signs. Around one-third of them have been found in Early Iron Age necropolises or other Iron Age burial sites associated with rich complex burials. It is usual to date them from the 7th century BC and consider the southwestern script to be the most ancient paleohispanic script with characters most closely resembling specific Phoenician letter forms found in inscriptions dated to c.825 BC. Tartessian is usually treated as unclassified (Correa 2009, Rodríquez Ramos 2002, de Hoz 2010) though several researchers have tried to relate Tartessian with known families of languages.

John T. Koch is an American academic, historian and linguist who specializes in Celtic studies, especially prehistory and the early Middle Ages, and received a personal chair at the University of Wales in 2007. A product of Irish-American cultural imperialism, Koch seems to be able to find Gaelic and other forms of Celtic in places that scholars have not been able to do since Celtic studies began. In 2009 and later he claimed that much of the Tartessian corpus can be interpreted as Celtic, with forms possibly of sufficient density to support the conclusion that Tartessian was a Celtic language, rather than a non-Celtic language containing a relatively small proportion of Celtic names and loanwords. A critical view of Koch’s work shows that it is not really convincing with inconsistencies, in form and content, and ad hoc solutions.

In 2011, Jürgenn Zeidler pointed out that Koch’s translations rely on Tartessian undergoing developments specific to Medieval Gaelic, rather than Celtic languages as a whole and, while the Tartessian script left “ample room for interpretation”, it was “hardly suitable” for Celtic or any other Indo-European languages. There was, of course, a strong vote for the Celtic hypothesis by Celtic nationalists and this can be found at Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2011.09.57. But remarkably Sir Barrington Windsor ‘Barry’ Cunliffe, the British archaeologist and academic in his recent book Britain Begins (2012) accepted Koch’s hypothesis without equvocation, a dangerous thing for any academic to do. Interestly enough Cunliffe also promotes the work of J.P. Mallory of Queen’s University, Belfast in his Quest for the Holy Gael. .

The non-Celtic Turdetani of the Roman period are generally considered the heirs of the Tartessian culture. Strabo mentions that “The Turdetanians are ranked as the wisest of the Iberians; and they make use of an alphabet, and possess records of their ancient history, poems, and laws written in verse that are six thousand years old, as they assert.” It is not known when Tartessian ceased to be spoken, but Strabo (writing c. 7 BC) records that “The Turdetanians … and particularly those that live about the Baetis, have completely changed over to the Roman mode of life, not even remembering their own language any more.”

The Gaelic Invasions

Irish tradition amply demonstrates that the Gaelic invasions of Ireland were LATE events in Irish history. This is confirmed by linguistics (there are no dialects or variants in early Gaelic, showing that Gaelic had recently arrived) and archaeology (there is no evidence of a mass migration since Neolithic Times). The invasions, when they did come, were of small scale but ruthless warriors. So who were they? Irish mythology says that their leader was Míl Espáine, the Soldier from Spain and his followers the Milesians.

Now the legendary Ninth Legion, Legio IX Hispana, the Spanish Legion, was one of the oldest and most feared units in the Roman Army. Put together in Spain by Pompey in 65 BC, it came under the command of Julius Caesar who was Governor of Further Spain in 61 BC, and served in Gaul throughout the Gallic Wars from 58 – 51 BC, the Legion was decisive in ensuring Caesar’s control of the Republic. After Caesar’s assassination it remained loyal to his successor Octavian. It fought with distinction against the Cantabrians in Spain from 25 – 13 BC but suffered terribly in the British revolt led by Boadicea (Boudica) in 60 AD, losing as many as 50 – 80 per cent of its men . However, several high ranking Officers who could only have served after 117 AD are well known to us, so we can safely assume that the core of the Legion was still extant in the reign of Hadrian, 117 – 138 AD.

The first great leader of the Fenians (later “Gaels”) in Ireland, Tuathal (Teuto–valos) Techtmar, was probably a Roman soldier, commanding Q-Celtic speaking mercenaries from Spain, so that the term “Gael” in Brittonic means just that, “raider” or “marauder”, literally “Wild Men of the Woods”. The earliest known source for the story of Tuathal Techtmar’s conquest of Ireland from the Aithech thuatha (Vassal Tribes) is a poem by Mael Mura of Othain AD 885. Mael Mura intimates that about 750 years had elapsed since Tuathal Techtmar had marched on the native British or Pretani ritual centre of Tara to create his kingdom of Meath, which would date the invasion to the early 2nd Century AD. This is probably approximately correct. The standard pseudo-historical convention is employed, however, to make him an exiled Irishman returning with a foreign army. He landed with his forces at Inber Domnainn (Malahide Bay). Joining up with Fiacha Cassán and Findmall and their marauders, he marched on Tara where he was declared king. Others conjecture that he invaded Ireland at the time of Agricola in Britain 77/78 to 84 AD. But certainly the Gaelicisation of Ireland, and most particularly Ulster, was about to begin.

Túathal is claimed to have fought 25 battles against Ulster, 25 against Leinster, 25 against Connacht and 35 against Munster. The whole country subdued, he convened a conference at Tara, where he established laws and annexed territory from each of the four provinces to create the central province of Míde (Meath) around Tara as the High King’s territory. He built four fortresses in Meath: Tlachta, where the druids sacrificed on the eve of Samhain, on land taken from Munster; Uisneach, where the festival of Beltaine was celebrated, on land from Connacht; Tailtu, where Lughnasa was celebrated, on land from Ulster; and Tara, on land from Leinster. Yet Tara was back in Gaelicised Pretanic hands at the time of Congal Claen in the seventh century.

The account in the Lebor Gabála Érenn, which does contain a shadow of history, is probably older and in this we see that Tuathal was born outside Ireland and had not seen the country before he invaded it. We can synchronise his birth or “exile” with the reign of the Roman Emperor Domition (81–96), invasion to early in the reign of Hadrian (122 – 138) and his death fighting the Cruthin under Mal mac Rochride, king of Ulster, at Mag Line (Moylinny near Larne, County Antrim in the reign of Antoninus Pius (138 – 161). This fits with Juvenal (c60 to 127 AD) who wrote “We have taken our arms beyond the shores of Ireland…” Tuathal may indeed represent the fictitious Mil Espáne (the Soldier from Spain), or even the Ninth Legion, the Legio IX Hispana, but that we will probably never know. His son, Fedlimid Rechtmar, later avenged him. Túathal, or his wife Baine, is reputed to have built Ráth Mór, an Iron Age hillfort in the earthwork complex at Clogher, County Tyrone.

The 5th and 6th centuries AD in particular are known to have been a period of unusually rapid development in the Gaelic language, as shown by the contrast between the general language of Ogham inscriptions and the earliest Old Gaelic known from manuscripts. There is little doubt that this was due to the widespread adoption of the Gaelic speech by the original inhabitants and the passage of older words and grammatical forms such as Brittonic (Welsh) into Gaelic. Gaelic and Brittonic were so similar at this period that the change would have been an easy one. By this time, therefore, Gaelic had become, according to Heinrich Wagner, “one of the most bizarre branches of Indo-European” since “in its syntax and general structure it has many features in common with non-Indo-European languages.” These included Semitic and Hamitic (Afro-Asian) influences, which point to the origins of such influences in the Middle East, North Africa, Southern Spain, abutting the coast of North Africa or a sub-stratum of very ancient pre-Aryan language or languages spoken by the first inhabitants of the British Isles.

But what of the parent Gaelic language itself here in Ireland? Celtiberian or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic was the extinct Celtic language spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula lying between the headwaters of the Duero, Tajo, Júcar and Turia rivers and the Ebro river. This language is directly attested in nearly 200 inscriptions dated in the 2nd century BC and the 1st century BC, mainly in Celtiberian script, a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, but also in Latin alphabet. Enough has been preserved to show that the Celtiberian language could be called Q-Celtic (like Gaelic), and not P-Celtic (like Brittonic and its parent Gaulish). Celtiberian would therefore appear to be the ultimate parent Celtic tongue of the Gaelic language, which originated very anciently from the first Celtic dialects of Indo-European in South-western Gaul (France) and came late to Ireland from Iberia (Spain) with the Romans.

The Myths of Peter Shirlow.

Peter Shirlow was a Professor in the School of Law at the Queen’s University of Belfast, then Professor of Conflict Transformation there and a key member of the Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice (ISCTSJ), which is linked to the Causeway Institute for Peace-building and Conflict Resolution, founded by my friends Jeffrey and Kingsley Donaldson. He has now left Queen’s University Belfast to become director and ‘Tony Blair Chair’ at the Institute of Irish Studies at the University of Liverpool. Dr Frank Shovlin from the University of Liverpool praised Shirlow for his “outstanding track record as a scholar, teacher and academic leader”. The Liverpool university’s Institute of Irish Studies was established in 1988. In 2007, the Irish government agreed to a multi-million pound endowment to fund the ‘Tony Blair Chair’ in Irish Studies. The additional funding has enabled the institute to expand the scope of its teaching and research and to expand their undergraduate and postgraduate degree programmes.

Shirlow’s latest book The End of Ulster Loyalism?, published in 2012 by Manchester University Press, was a product of his attachment to Loyalist groups. In this book he advises that “Using their experience as a deterent, Loyalists can show the motivations behind violence and how these were misplaced, and the burdens imprisonment placed upon family members. Doing so is an invaluable way of transmitting lessons about the past, dispelling myths and falsehoods and discouraging its repetition.” “One myth located within loyalism is that the Cruithin as (sic) the original stock of Ulster driven out by the Celts. Therefore the Plantation of Ulster was a reclaiming of a homeland. Much of that work has been produced by Adamson (1991).There is no archaeological evidence for such a people”

Such a mischievous, and indeed libellous, rendering of my work is not unusual but what is the real purpose behind it?. The poor scholarship it displays is obvious, but why single out my work?. The Cruthin, of course, are a historically attested people in Ireland, who occupied large parts of the modern counties of Down, Antrim, Londonderry and Donegal in the early medieval period and anciently the whole country before the coming of the Belgae from Great Britain and then the Gaels “Marauders” from Roman Spain (led by Míl Espáne or Miles Hispaniae, meaning “Soldier of Spain”) . Their name in Middle Irish Gaelic is Cruithnig or Cruithni; Modern Irish Gaelic: Cruithne .Their ruling dynasties included the Dal nAraidi (Dalaradia) in southern Antrim, the Ui Echach Cobo (Iveagh) in western Down and the Cenél Conaill in Donegal. Early sources preserve a distinction between the Cruthin and the Ulaid, who gave their name to the kingdom of Ulster, although the Dál nAraide claimed in their genealogies to be na fir Ulaid, “the true Ulaid”. The Loigis, who gave their name to County Laois in Leinster, and the Sogain of Connacht are also claimed as Cruthin in early Irish genealogies.

And they have left a wealth of archaeological artifacts in Ireland because of a variety of factors, among them the continued survival of a predominately rural way of life, for many of the artifacts blend effortless into the surrounding environment. Dolmens, court cairns, passage caves, stone circles, standing stones, Ogham stones, ring fort earth works, crannogs, round towers, high crosses, churches, monasteries, abbeys and castles abound. Rath Mor of Moylinne, was a residence of the kings of Dalaradia, the Kingdom of the Cruthin. It is an ancient archaeological site situated near Lough Neagh, in the present parish of Donegore, and the place is still known as the Manor of Moylinne. After an existence of eleven hundred years, the royal habitations were burned to the ground in 1513.

O’Neill, i.e.. Art, the son of Hugh, marched with a force into Trian Congail, (the Third of Congal Cláen, which includes Belfast) and burned Moylinne (in Antrim), and plundered the Glynns. The son of Niall, son of Con Mac Quillin, overtook a party of the forces, and slew Hugh, the son of O’Neill, on that occasion. On the following day the force and their pursuers met in an encounter, in which Mac Quillin — namely, Richard, the son of Roderick— with a number of the men of Alba (“Scotland”), were slain. After that destruction of the habitations in Rath Mor Mag Uillin, the Castle of Dunluce became the chief residence of the “Mac Quillins” (Gaelicised Brittonic ap Llwelyn), and the deserted Rath Mor was never re-edified. Rath Mor Mac Uillin, signifying the Great Rath of McQuillin, was the original designation of the spot where stood the ancient palace of the Cruthin kings of Ulster. It was often written Rath Mor Magh Line, again Moig Cuillin, and now Moylinne.

Furthermore it was not I, but Professor Emeritus John MacQueen of Edinbugh University, who first suggested in 1955 that the Kreenies (of Galloway) were by origin Cruithnean (Cruthin) settlers, probably fishermen and small farmers, from Dal Araide (Dalaradia), just the people who might be called Gossocks or servile people by the Cumbric native Britons they found in Galloway (my parentheses). So what’s the problem here? Much of it stems, I fear, from the pronouncements of JP Mallory, the Irish-American Professor Emeritus and “Elder Statesman” of Archaeology at Queen’s, who describes the early “Irish” as those who spoke the earliest attested version of the “Irish” Language, even though that language is anciently called Gaelic and still is, whose speakers were pre-dated in Ireland by thousands of years by the indigenous inhabitants…Says it all, doesn’t it?

That icon of “serious” scholarship, that doyen of revisionist Irish historians (I mean this man is a Celebrity, a Superstar among his kind!), Robert Fitzroy (Roy) Foster, has written in his chapter History and the Irish Question from Interpreting Irish History -The Debate on Historical Revisionism Irish Academic Press, Dublin 1994, “Still the depressing lesson is probably that history as conceived by scholars is different to what it is understood to be at large, where “myth” is probably the correct, if over-used, anthropological term. And historians may overrate their own importance in considering that their work is in any way relevant to these popular misconceptions- especially in Ireland.The habit of mind which preferred a visionary Republic to any number of birds in the hand is reflected in a disposition to search for an Irish past in theories of historical descent as bizarre as that of “the Cruthin people” today (I. Adamson’s book Cruthin: The Ancient Kindred (Newtownards,1974) is interpreted by Unionist ideologues as arguing for an indigenous ” British” people settled in Ulster before the plantations), the Eskimo settlement of Ireland postulated by Pokorny in the 1920s ,the Hiberno-Carthiginians of Vallancey, or the Gaelic Greeks of Comerford.” How wonderfully cynical, petulant and trite. And, of course, he is completely wrong.

Yet in Wherever Green is Read in the same volume, Seamus Deane more sensibly, and much more intelligently, argues. “Perhaps it is now time for the stereotype to invert, so that the South can start reading the jargon of the North’s newly aquired writerly status, complete with its “myths” of the “Cruithin” (Ian Adamson’s redaction of the Gaelic story of dispossession, much favoured by the UDA and, increasingly, by Glengall Street) its evangelical religion and, of course, its poetic rhetoric” . But for Peter Shirlow this is a non-starter, for such “myths and falsehoods” should be dispelled and their repetition discouraged, leading in my view inexorably not only to the End of Ulster Loyalism, but also to the separation of “Scotland” from “England”, and the loss of the United Kingdom’s seat on the United Nations Security Council, with dire ramifications for World Peace.

Common Sense was published by the (New) Ulster Political Research Group and not, as Shirlow has erroneously stated, by the Ulster Democratic Party..He should know that these groups were very far from being the same thing. This is poor scholarship indeed. The real myths and falsehoods are those of the Cunliffe/Koch myth of Tartessian “Celtic”, the Mallory/Warner myth of the first Irish being “Irish” speakers to push them as far back in history as possible and the Woolf/Frazer myths of the “Northern Ui Neill” and Gaelic Dalriada, the Cenel Conaill and Epidians of whom were actually Cruthin or Pretani. In accepting these and deprecating the Cruthin, such myths have become the Myths of Peter Shirlow himself.

Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice, QUB.

Queen’s University, Belfast has recently made a significant investment in what it claims is its long-established expertise in conflict and peace processes by founding a dedicated Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice. At the heart of this development it says is the recognition of the inseparability of social justice from sustainable processes of conflict transformation and, ultimately, of peace. But what if part of the problem lies in this Institute itself? What happens then?

The purpose of the Institute is claimed to be facilitation of sustained interdisciplinary collaboration in research and teaching and to provide strategic focus to support world class research in this field. The Institute says it will promote cross-School, cross-Faculty and inter-institutional co-operation that leads to high quality publications and will engage research users and other practitioners to enhance the non-academic impact of the work being undertaken. In Northern Ireland it is actually doing the opposite by acting to destabilise those ongoing workers within the community with whom it disagrees.

The Institute was established on 1 August 2012 with Professor Hastings Donnan as its first Director. ISCTSJ claims to connect the perspectives of all those who seek to contribute to conflict transformation and social justice – from the insights of world leading researchers to the experience of practitioners, policy makers, politicians and activists. This is in essence not true, for I had never heard of this Institute until Peter Shirlow’s poor research about the Cruthin/Pretani and the Common Sense document was brought to my attention by senior community activists. It claims to strive to create dialogue within which all voices can be heard and to underpin the pursuit of peace through world class research. But yet, as we have seen, it attempts to destroy those voices of long-term activists within the field in Northern Ireland which do not accord with its own out-dated and retrogressive views of Irish history , marginalising the history of the Cruthin and treating Gaelic pseudo-history as real, so maintaining an anti-British or Britophobic ethos in Ireland, and indeed in northern, southern and western Great Britain ( “Scotland”,” England” and “Wales”), as well.

Each year the Institute will announce a Priority Theme to provide a focus for its activities and to stimulate innovative and imaginative research collaborations on a flexible set of broadly interdisciplinary topics related to conflict transformation and social justice. This will be led by two Institute Fellows from different disciplines at Queen’s. The Priority Theme will normally be announced a year in advance.

The Institute will also support a number of Interdisciplinary Research Groups that will develop a programme of activities including seminars, workshops, conferences, exhibitions and performances whose overall objective is to enrich understanding of conflict transformation and social justice. Interdisciplinary Research Groups will play a key role in assisting the Institute realise its goals of attracting leading international researchers and involving research users, policy makers and practitioners in a way that maximises research impact. Research training at postgraduate level will be an increasingly important element of the Institute’s core activities, and will include the development of a new, cross-disciplinary Masters programme in conflict transformation and social justice.

But will it challenge its own? No, of course it won’t. They’ll all swing togethaa, togethaa they will swing, make lots of lovely PhD’s and Masters for themselves, while trying to impose their own prejudiced sense of reality on all of us. And they’ll award each other every accolade they can in doing so. Do we need them? No, of course we don’t. We long-term community activists in Dalaradia and the Ullans Academy promoting Common Identity are more than capable of looking after ourselves without their interference. In fact, my own opinion is that they should be disbanded altogether and the University of Ulster, with a much more experienced group of scholars, like the incomparable Professor Paul Arthur, Honorary Professor in Peace Studies there, continue as the Academic Centre of Excellence in Conflict Studies in Northern Ireland.

History is primarily a record of human relationship with a vast network of variation in the manner of its evolution. Now is the time to widen its perspective beyond the religious and political divide. People do not change their minds, rather their horizons are widened. We begin to comprehend that what we thought was the whole of reality is but a small part and that a representation. Nobody can claim to own reality just as nobody can legitimately claim that theirs is the only view of history. And that is where we have seen that the Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice of Queen’s University is fundamentally flawed.

The Nazification of Celtic Studies.

The German Intelligence Services (Abwehr) in Northern Ireland were very effective before the last World War and played a large part in the Belfast Blitz. Why were they so effective?. The answer lies with their top spy in Ireland just before the War, Adolf Mahr. One of his academic colleagues was the fine intellectual Emyr Estyn Evans whose testimony on Mahr follows, as contained in a superlative book Ireland and the Atlantic Heritage – Selected Writings. This was given to me by his son Alun and wife Gwyneth Evans on 27 September 1996, during my tenure as Lord Mayor of Belfast, as a memento of my participation in the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health’s Centenary Meeting, Queen’s University of Belfast organised by Alun that month.

Emyr Estyn Evans (1905-1989) was born in Shrewsbury, England, of Welsh parentage. He studied under H.J. Fleure at Aberystwyth and in 1928 moved to Queen’s University, Belfast, where he founded the Department of Geography and held a Chair from 1948 to 1968. He helped to establish the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum at Cultra, County Down, in 1963, and in 1970 became the first Director of the Institute of Irish Studies. His books include France (1937), Irish Heritage (1942), Mourne Country (1951, rev. 1967), Irish Folk Ways (1957), Prehistoric & Early Christian Ireland (1967), and The Personality of Ireland (1973, rev. 1992).

Adolf Mahr Archaeologist and Nazi Spy

“It may be noted that earlier in this century the making of some axes for a commercial purpose had been a minor industry in mid-Antrim. W.J. Knowles records that genuine axes made of stone from Tievebulliagh were so plentiful (he himself said that he obtained over 2500 from Glen Ballyemon) and were so keenly sought by private collectors and museums that local farmers began making them for sale. This put an end to collecting for a time.

One of the keenest collectors of axes and other artifacts later on was Dr Adolf Mahr, Director of the National Museum in Dublin. Born in Austria, he was a good archaeologist and I came to know him well. He published a comprehensive survey of Irish prehistory in 1937. In Dublin he became a powerful force. Membership of the Royal Irish Academy is a much-prized honour to which I did not then aspire. All I know is that Mahr told me one day that I was now an MRIA. (Nowadays, quite eminent people are proposed more than once before they succeed in being elected, and I did not even know that my name had been proposed.) Mahr invented what he called ‘the ether test’, by which, he claimed, the presence of machine-oil on the surface of a polished axe could be detected and forgeries revealed. We often discussed archaeological topics and monuments, and I showed him many of the famous sites in Northern Ireland. Only later did I suspect that he may have been spying out the land for a sinister purpose.

His appointment as Museum Director in Dublin when there were, I believe, excellent applicants for the post from Britain, seemed to illustrate the strength of the hatred of all things British prevailing in Éire in the years following Partition. In fact it was another German who was first appointed, Mahr succeeding him on his early death. I could not believe the rumour that, like many other scholarly Germans, Mahr was a dedicated Nazi. But apparently he had been a young museum assistant in Germany looking for a faith, and though first tempted to join the Society of Friends, eventually he fell under the evil spell of another Adolf. I was profoundly shocked to learn subsequently that he had told a Dublin archaeologist that after the war, following the German victory, he would see I was made Gauleiter of Ulster!

Suspicion fell too on another German, a certain Herr Hoven, then living in Belfast, though officially domiciled across the border. He often called to see me, and I once asked him when he hoped to return to Germany. His unguarded reply, ‘Not until early September’, seems to have been prophetic, for war was declared on 3 September 1939. I should add that neither Mahr nor Hoven, to the best of my knowledge, was ever charged with spying, for legally they were residents in a neutral country.

Mahr wanted to enrich the collections in Dublin and questioned both the claims of the Belfast Museum and the quality of its staff and of the inspectorate in Northern Ireland. The senior civil servant who was in charge of historic monuments was a Trinity College historian who had little archaeology, and Mahr described him to me in this way: ‘He is just a big fat elephant: he is hard to move, and ven he does move, he goes in the wrong direction.’ Classical archaeology was then taught at Queen’s in Belfast but no Irish archaeology, and no prehistory.

Mahr appeared to take a special interest in coastal sites, especially on the Lecale coast of South Down, but only some years later did I discover a possible explanation. In 1941 I had occasion to check the condition of some stone monuments there which I had listed earlier. I found that the roof of one of the early corbelled structures had been removed, and when I peered inside I found myself staring into the barrels of half-a-dozen heavy machine-guns, pointing out to sea. Belfast was being heavily bombed by German planes at the time (as I well remember, for the house near the University where I then lived was hit by an incendiary bomb) and I came to realize that it was the possibility of their use as defensive posts which probably explained Mahr’s particular concern for these apparently innocent historic monuments along an ‘invasion coast’.”

Mahr tried to return to Ireland after the War. But de Valera had had enough and would not permit it. However his influence remained strong in the perpetuation of the Hallstatt myth of early “Celtic” origins in Austria, the birthplace of both Mahr and that other Adolf, his hero and devoted master. The Gaelic myth itself originated in the nineteenth century Celtic Romantic movement and was pursued by Patriot Poets, as well as by writers of popular history and Irish nationalist political propaganda, including “serious historians”. The cell structure of academic elitism protected those Celtic scholars who continued to disseminate notions of a Gaelic Aryan Race, to whom Ireland rightfully belonged.The Hallstatt myth is slowly losing ground, although it was still being promulgated by the BBC in its recent series The Celts: Blood, Iron and Sacrifice. However this myth is unfortunately now being replaced by new myths for old. The Mallory/Warner myth of Irish/Irelander. the Koch/Cunliffe myth of Tartessian Celtic origins and the Woolf/Frazer myth of Gaelic Dalriada and the “Northern Ui Neill” will create their own continuing difficulties for the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland for the forseeable future. And indeed for the whole World if the United Kingdom loses its seat on the Security Council of the United Nations.