The Ancient Era

In 1991, I published The Ulster People under my Pretani Press imprint. My friend, Professor Frechet of the Sorbonne wished to translate it into French but his death prevented that, and the fact that some Irish academics wanted to burn it dissuaded me from bringing out a second edition. Twenty years later, on January 27th, 2011, Holocaust Memorial Day, I visited the Exhibition on the Millisle Jewish Refugees in the North Down Museum and was geatly moved by it. I wrote a comment under James O’Fee’s one in the book of comments provided by Sandra Baillie. Sandra has written in Presbyterians in Ireland about the “Cruithin Myth” and the fact that ” this story has not been taken very seriously by academics or the general public” I also bought Marsden Fitzsimmons beautiful little book on Travels with Columbanus , which mentions neither the Cruthin nor Mary O’Fee. Furthermore Marsden and Sandra have obviously not read The Ulster People , or know that those academics wished to burn it. But times have now changed as we witness the rebirth of Pretania, the obvious result of Brexit, so here it is again.

I will start with my native Conlig, named in Gaelic as the “Stone of the Hound” after the Standing Stone above the village. We have no evidence of human habitation in Ireland before the retreat of the ice-sheets which covered almost the whole of the island until the end of the Ice Age. The first settlers perhaps arrived around 10,500 BC. They probably came from the western shores of Britain, the archaeological evidence tending to suggest either from Galloway in south-west Scotland or Cumbria in northern England. These flint-users were hunters, fishermen and food-gatherers who lived predominantly along the coast or in river valleys such as the Bann. They are our primary ancestors, the ancient Pretani, accounting for 90% of our genes.

In the period after 4000 BC, during the Neolithic or Late Stone Age, farming was introduced. Crops were grown, animals kept, and many new types of implement were introduced. For the first time man began to leave his mark on the thickly wooded Irish countryside.The tombs and monuments made by these Neolithic farmers are called ‘megalithic’ (i.e. made of large stones), such as the court cairns and dolmens. Ireland is extremely rich in such antiquities, with over 1,200 stone monuments surviving today. The court cairns, which are mainly located in the north of the island, are also found in south-west Scotland, and Séan O Ríordáin commented: “The tombs and the finds from them form a continuous province joined rather than divided by the narrow waters of the North Channel.” This connection with Scotland is evidence of the ancient link which has existed throughout history between what W.C. Mackenzie described as “two great and intimately associated peoples”.

Some of the largest and most impressive monuments made by the Neolithic Irish are located in the Boyne valley, the best-known example being the great passage tomb at Newgrange, of which Michael Herity wrote: “Newgrange is the most famous of a group of over 300 passage graves built in cemeteries throughout Ireland [which] are monuments to the most capable organisers, architects and artists ever to have entered and influenced Ireland in the whole of prehistory.” New techniques in dating have suggested that Newgrange could have been built around 3350 BC, making it one of the earliest stone buildings in the world. The legacy of Ireland’s megalithic builders is of fundamental relevance to us today, for, as Fleure pointed out, “The megaliths are not a matter of a vanished people and a forgotten civilisation; they belong to the core of our heritage as western Europeans.” P.A.O. Síocháin also wrote: “No longer can we look on these as cold stones from a long dead era. Warm hands once held and gave them meaning and purpose; touch them and you touch your past.”

Of the Neolithic period Peter Woodman wrote: “This part of Ireland’s prehistory lasted nearly two thousand years and in that period some remarkable changes took place, changes which probably do more than any others to create the Ireland which enters history several thousand years later.” The legacy of these early settlers of Ireland is very much our heritage, for, despite the seemingly great distance in time which separates us from them, we are in reality just the latest generations to have sprung from a very ancient people. As archaeologist Peter Harbinson commented: “We can say in all probability that [they] represent the basic human stock onto whose blood-gene pool all subsequent peoples were ‘grafted’, so they may truly be described as the first Irish men and women, the ancestors of the Irish people of today.”

The Elder Faiths

Just as these first peoples of Pretania (the British isles) were our distant ancestors, and we must therefore share many of their physical attributes — amended of course by the various invading minorities who turned their attention to Ireland in later historical periods — so also is it quite conceivable that we have retained some residue of the personalities of these early peoples, particularly in our relationship to the land and the seasons, a matter of life-giving importance to an agricultural community. Whatever beliefs they held — what we now call the Elder Faiths — have obviously long disappeared, yet perhaps it is possible to detect faint echoes of them in long-established rural superstitions and folk memories. Estyn Evans wrote that archaeology was now tending to “confirm what recent anthropological, linguistic and ethnographic research suggests, that the roots of regional personality in north-western Europe are to be found in the cultural experience of pioneer farmers and stockmen, quickened by the absorption of Mesolithic fisherfolk… One should probably look to the primary Neolithic/megalithic culture rather than to the intervening Bronze Age as the main source of the Elder Faiths.”

Professor John Kelleher commented: “The culture that reasserted itself in the fourteenth century and continued viable… down to the early seventeenth century was but the latest stage of the culture that had existed continuously and strongly since prehistoric times… We can be sure that much of it survives in the native population, if only below the level of consciousness.”The visible reminders of Ireland’s ancient inhabitants — the dolmens, stone circles and other burial monuments — are still treated with respect by country people. Tampering with these monuments can even today, according to some, bring bad luck upon the perpetrators, and archaeologists have been refused permission to excavate some monuments because of local resistance. At the beginning of the century W.G. Wood-Martin wrote: “Facts which show the resentment formerly felt by the country people at their disturbance, are well known. It is noteworthy that these former objects of the peasants’ veneration were erected by an early wave of population. It may be suggested that their preservation by means of veneration for traditional beliefs points to the continued influence, up to a very late date, of their builders.” Ironically, this veneration can today prove itself a useful ally to our present concerns with conservation of the natural environment.

In 1989 Irish documentary-maker Eamon de Buitléar filmed the wildlife which inhabited an ancient overgrown ringfort, which for hundreds of years the local population had left untouched because of their belief that the ‘little people’ still lurked among its bushes and trees. As a result the resident animals had flourished, with little fear of man. “Animals realise these are the places to inhabit. There are cases of council workmen refusing to make a road through an area containing a ‘fairy fort’ because they have certain knowledge of men elsewhere who were cursed for interfering with such places. These beliefs guarantee conservation.” A Fairy Thorn has been preserved in the middle of what was once a row of houses beside St Aidan’s Parish Church, Blythe Street (“Blythe” means “Happy” in Ullans or Ulster Scots), in the Sandy Row, Belfast, near to the former Watson Street, where I wrote The Cruthin. . I saw it again at the funeral of Charlotte Adams, mother of the former Lord Mayor of Belfast, Bob Stoker.

There has also survived in Ireland an extensive body of customs and beliefs regarding the observance of particular times, dates and festivals — centred around the practical needs of a people whose livelihood was based upon the growing of corn and the raising of cattle, in other words a farmer’s calendar. Kevin Danaher has shown that this ‘folk calendar’ was not Celtic, and suggests: “We may conclude that the four-season calendar of modern Irish tradition is of very high antiquity, even of late neolithic or megalithic origin, and that its beginnings predate the early Celts in Ireland by at least as great a depth of time as that which separates those early Celts from us.”

Estyn Evans summarised the importance of this long period of habitation and consolidation, remarking also upon the evidence of a regional diversity: “The [archaeological] evidence… reveals one essential truth: that we are dealing not with mythical ‘lost tribes’ but with ancestral West Europeans, physically our kinsmen, who were the first Ulster farmers, pioneering in a way of life which has persisted through more than 5000 years, carrying with it attitudes of reverence for the forces of nature and leaving indelible marks on the face of the land. The landscape they helped to fashion was to be the heritage — for good or ill — of all later settlers, Celt and Christian, Norman and Planter. Already by the late Neolithic, farmers practising shifting cultivation and rearing livestock had penetrated all the major upland areas in the province and had reduced considerable stretches of forest to grassland, scrub or bog.

During the early Bronze Age it seems likely that ‘much of the remaining forest was destroyed or degraded’ by cultivators and stock-raisers who had learnt to use metal axes and whose favourite cereal was barley, a crop which has become dominant once more in recent years. No doubt many forests remained in the ill-drained lowlands, but we must not assume that they were entirely virgin. Rivers and lakes among the forests would have harboured mesolithic remnants, and the damp lowlands would anyhow have acted as divides, so that different cultural areas can be discerned. Repeatedly, Antrim and North Down — the prehistoric core-area — stand out in Bronze Age distribution maps as a distinctive region, supporting a vigorous metal industry and a far-reaching export trade despite poor mineral resources.”

The Carthaginians

The introduction of metallurgy into Ireland is generally ascribed to those artisans who also made a type of pottery to which the name Beaker has been given. Three objects found near Conlig, County Down, include a copper knife or dagger of Beaker type, a small copper axe of early type and a small copper dagger of more advanced type. The mines of Conlig are still extant and the area was probably the main source of copper ore in the north.

The working of bronze commenced in Ireland around 1800 BC. In the beginning the ancient Irish bronzesmiths provided the needs of much of Britain, and to a lesser extent of northern and western Europe as well. That such a great bronze industry should be carried out on an island where tin, which accounts for some 10 per cent of the alloy, was not mined to any degree, indicates that this component must have come from Cornwall, Brittany or even North Spain. It was once thought that the new pottery styles and burial practices adopted at this time indicated large immigrations into Ireland, but more weight is now given to indigenous development, with ‘influences’ rather than ‘invasions’ coming in from abroad.

About 1200 BC there was a change in the type of artefacts produced and a whole new variety appears, distinctive of what we know as the Late Bronze Age: there were torques of twisted gold, gorgets of sheet gold, and loops of gold with expanded ends used as dress fasteners. This was indeed a Golden Age for Ireland, peaceful and prosperous, controlled by a society in which craftsmen were even more in evidence than warriors, and open to trading influences from abroad. Irish artefacts have been discovered not only in nearby France and Scandinavia but as far afield as Poland.

The advancement of the ancient people of those times in the science of navigation has been very much underrated, and the geographer. E.G. Bowen has concluded that the seas around Ireland were “as bright with neolithic argonauts as the Western Pacific is today.” Certainly, with north-east Ireland and south-west Scotland separated, at their closest points, by only thirteen miles, and considering that much of the land was still covered with dense forest, the North Channel of the Irish Sea would have acted not as a barrier but as a more effective means of communication between these two areas.

The Prophet Ezekiel, writing about 500 BC, in his address to the people of Tyre (in ancient Phoenicia), gives an indication of such a widespread trading network: “They have made thy shipboards of fir trees of Senir, and have taken cedar trees of Lebanon to make thy masts. Of the oaks of Bashan have they made thine oars; the company of Asurites have made thine hatches of well worked ivory, brought out of Chittim. It was of fine linen and Phrygian broidered work from Egypt which thou madest thy spreading sails; and thy covering was of the blue and purple of the isles of Elishas.” Could this mention of the ‘rich purple dyes’ be a reference to the British Isles? The purple dyes of our islands were celebrated among the later Greeks and Romans and were very expensive.

Between 600 and 500 BC ‘Periplous’ of Himilco, the Carthaginian, made the earliest documentary reference to Ireland. The Greek philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the fourth century BC, wrote of

an island called Ierne which lay at the edge of the continent, and stated that it was discovered by the Phoenicians. The sister island was known as Albion. These names had come to the general knowledge of Greek geographers such as Eratosthenes by the middle of the third century BC. Ierne in Phoenician would mean the “farthermost” island. Between 330 and 300 BC the Greek geographer and voyager Pytheas, in his Concerning the ocean, gave us the earliest reference to the British Isles, calling them the Isles of the Pretani (Pretanikai nesoi), probably an indigenous name, the meaning of which we will never know. The name of the island of Islay is of similar pre-Indo-European origin. The ‘Pretani’ are thus the most ancient inhabitants of Britain and Ireland to whom a definite name can be given. As there is no evidence of any major immigrations into Ireland after the neolithic period, the Pretani would appear to be the direct descendants of the earlier peoples, or at least a dominant segment within the native population. In the later Irish literature ‘Pretani’ would become ‘Cruthin’.

Ireland was now to encounter a significant group of immigrants — the “Celts” — who were to bring with them a new and rich language. We cannot be certain as to when the first groups of “Celtic” people arrived in Ireland. To this day, there is no evidence which can place “Celtic” settlements in Ireland before the first century AD or the first century BC at the earliest. The once-popular notion that the “Celts” were in Ireland from time immemorial has long been discarded, though some academics with Gaelic nationalist sympathies, including archaeologists, continue to state otherwise. Another popular belief, however, that the “Celtic” immigrants, when they did arrive, swamped the local inhabitants and became the majority population, has proven harder to dislodge. Yet it is now generally accepted that when those groups of peoples we loosely call “Celts” arrived in Ireland, they did so in small numbers. A seminar held by the Irish Association of Professional Archaeologists in 1984 acknowledged that any “Celtic” ‘invasions’ were more than probably carried out by numbers “far inferior to the native population(s)”.

Archaeologist Peter Woodman has also pointed out: “The gene pool of the Irish was probably set by the end of the Stone Age when there were very substantial numbers of people present and the landscape had already been frequently altered. The Irish are essentially Pre-Indo-European, they are not physically Celtic. No invasion since could have been sufficiently large to alter that fact completely.” Popular notions, particularly when they are interwoven with cultural pride and romantic ideas of a nation’s ethnic identity, make it difficult at times to permit new awareness from percolating into public consciousness. While this is forgivable for the general public, it is harder to understand why some academics and media presenters still talk today of the Irish as being a ‘pure’ Celtic people, despite all the mounting evidence to the contrary. Although they had come as a minority, however, the Celts eventually achieved a dominant position in those areas that came under their sway, and they formed a warrior aristocracy, wielding power over the mass of indigenous inhabitants.

The “Celts”

The word ‘Celtic’ is primarily a linguistic term which is applied to a closely related group of dialects referred to as ‘Indo-European’. There is little doubt that the Celtic tribes of Europe were composed of different physical types, and that Celtic speech was adopted by or imposed upon large numbers of subjects. The Celts became dominant over most of Central Europe, and various groups of Celtic-speaking peoples migrated from there to other parts of the continent. When the Roman empire expanded, her legions came into direct confrontation with this “Celtic” heartland, and Caesar’s famous ‘Gallic Wars’ (58-51 BC) not only gives us a personal account of Gaul (modern-day France, Belgium, northern Italy and part of Germany) but of how the Romans extinguished its independence. It was quite possibly in response to Roman expansion that some Celtic-speaking groups crossed from continental Europe to the British Isles.

Yet the Roman destruction of Celtic power had been preceded by another, far more fundamental encounter. The intrusion of the Celts themselves into Europe must have been, as Professor Thomas Markey noted, “one of the most wrenching cultural collisions of all time, the clash between Indo-Europeans and non-Indo-Europeans in early Western Europe.”

What of the pre-Celtic inhabitants of Ireland? Markey pointed out that “Ireland was the final stronghold of the Megalithic peoples in the West, and the Celts who subsequently settled there were the last Indo-Europeans to come into contact with them.” These pre-Celtic people obviously didn’t disappear, but survived, and remained as the majority population. As Francis Byrne noted: “The earlier, non-Indo-European, population, of course, survived under the Celtic overlordship. One group in particular, known to the P-Celts as Pritani and to the Irish as Cruithni, survived into historical times as the Picts or ‘painted people’ of Scotland. The Cruithni were numerous in Ulster too, and the Loíges of Leinster and possibly the Ciarraige of Connacht and north Kerry belonged to the same people.”

Although it is now clear that the Celts were relative latecomers to Ireland, and that when they arrived here they most probably did so in small numbers, their presence has been accorded a remarkable prominence, not the least because of their introduction of a new language. The 1984 seminar held by the Irish Association of Professional Archaeologists, attended not only by archaeologists but representatives from linguistics and environmental studies, deliberated on the theme ‘The origins of the Irish’, and the moderator of the seminar pointed out: “An Irishman was defined as one who spoke either the earliest form of the Irish language or a language immediately ancestral to it. Such a definition then pertains to the appearance of Irish-speaking Celts and is not… to be confused with the arrival of the first people in Ireland.”

Thus the earlier, majority population of Ireland, who had inhabited the island for a greater length of time than that which separates the Celts from us today, were denied the epithet ‘Irish’ in favour of the Celts. The ‘earliest form of the Irish language’ referred to was not, as one might reasonably suppose, that spoken by the original inhabitants, but the specific language, now known as Gaelic, introduced by an incoming Celtic minority.

As far back as 1906 Eoin McNeill, founder of the Gaelic League and one of the most eminent of Irish historians, believed that his research had finally penetrated through the academic obsession with the Celts to allow us to acknowledge the vital part played in our heritage by the original inhabitants. He wrote that “the hitherto current account of pre-Christian Ireland has belittled and overclouded the vast majority of the Irish people for the glorification of a dominant minority,” and he felt he could now safely assert that “the one outcome of [these] studies has been to restore the majority to the historical place of honour from which they have been ousted for a thousand years.” He had obviously spoken too soon. The Celts have certainly contributed richly to the cultural legacy of the Irish, yet they are only one aspect of a heritage which is more ancient and varied than people are generally aware.

Ironically, it is through the very languages introduced by Indo-European peoples such as the Celts that we are now beginning to learn more about the pre-Celtic peoples who were finally to adopt such languages as their own. Heinrich Wagner wrote: “It is likely that the [Celtic invasions] did not involve large numbers of Indo-European-speaking peoples, a view which has led a number of scholars, including myself, to believe that in the British Isles Indo-European language as imposed by small bands of Celtic-speaking invaders from the Continent must have been influenced strongly by the speaking habits of a predominantly non-Celtic population.” So Gaelic would eventually become, not a pure Celtic language, but, as David Green described it, “simply the linguistic expression of the Irish people… a language made in Ireland.”

The 5th and 6th centuries in particular are known to have been a period of unusually rapid development in the Gaelic language, as shown by the contrast between the general language of Ogham inscriptions and the earliest Old Gaelic known from manuscripts. There is little doubt that this was due to the widespread adoption of the Gaelic speech by the original inhabitants and the passage of older words and grammatical forms into Gaelic. By this time, therefore, Gaelic had become, according to Heinrich Wagner, “one of the most bizarre branches of Indo-European” since “in its syntax and general structure it has many features in common with non-Indo-European languages.” These included Semitic and Hamitic influences.

Linguistic analysis is today affording us new insights into this intermingling of peoples. In studying the various branches of ‘Indo-European’, scholars had of necessity to define what it actually is — its permissible vocabulary and grammar — and thereby define what it is not — its impermissible vocabulary and grammar. This ‘impermissible vocabulary and grammar’ was obviously that borrowed from the pre-Indo-European inhabitants of Europe. As Thomas Markey explains: “No Indo-European language displays an acceptably Indo-European word for ‘apple’, a fruit that was an invaluable part of a primitive diet. The apple was presumably unknown to Indo-Europeans in their primordial homeland, wherever that was… We may conclude that, as nomadic herdsmen, the Indo-Europeans borrowed the apple, along with terms for it, from the Megalithic farmers… We now know that something like twenty-eight percent of the Germanic lexicon, including such common words as English folk, have non-Indo-European origins. The language handbooks that have been accepted as the standard for decades are now badly in need of extensive revisions.”

This linguistic study, according to Markey, has meant that “We are now equipped with a potent filter device, a negative definer of non-Indo-European in the West [and] the silence that has long surrounded the pre-Indo-Europeans has finally been made to speak.” Markey was able to identify certain fundamental differences between the two cultures. Pre-Indo-European society was of a matrifocal, non-stratified nature, based on a sedentary, horticultural lifestyle, where there existed advanced boat building and navigational techniques as well as a sophisticated knowledge of astronomy. Indo-European society, on the other hand, was of a patrifocal, stratified nature, with a nomadic lifestyle based on animal husbandry, and where there was a lack of boatbuilding and navigational techniques and only a rudimentary knowledge of astronomy. As Markey concludes: “Clearly, the Megalithic peoples gave more than they got. They lost their language, while the Indo-Europeans pillaged it for loans… The invader was technologically inferior to the resident.”

It was the discovery of iron around 800 BC which was to allow these Indo-European peoples to initiate a major technological revolution of their own, and Europe was to enter its Iron Age. The early phase of the use of iron implements in Ireland extended over about the last two centuries BC and a little beyond. It is marked by the appearance in north-east Ireland of such equipment as iron swords and their bronze scabbards whose ornamentation is based on continental rather than British models. This is consistent with the growing isolation from Britain apparent at the end of the Late Bronze Age. Implements of Late Bronze Age type continued to be a marked feature and burial customs persisted from the earlier Age. Excavations at Downpatrick showed that life continued unbroken.None of this can be taken as evidence of a Celtic migration to Ireland, rather it shows that an ancient land of craftsmen were learning new ways. If there was a movement from the Continent it may only have been of chieftains and their retinues or of craftsmen alone. Originating, however, in the 19th Century Celtic Romantic movement, the Celtic myth has been pursued by writers of popular fiction and Irish republican nationalist political propaganda. The myth has become the reality and the reality has become the myth.

When the first groups of Celtic-speaking peoples did eventually begin to consolidate their position in various parts of Ireland, their kings took over for their royal sites the neolithic burial places still sacred to the local inhabitants. This has been partially confirmed by archaeological findings — for example, by the co-existence of Celtic Iron Age earthworks and a neolithic passage grave at the ‘Mound of the Hostages’ at Tara — and by Gaelic practice itself: the neolithic burial site at Knowth was chosen by the local Uí Néill kings of northern Brega as their centre from the eighth century onwards. As Francis Byrne remarked: “There can be no doubt at all of the extraordinary continuity of tradition exemplified at sites such as Tara and Knowth. This is in itself a strong argument for the survival of large elements of the megalithic people and of their beliefs in Ireland under the later Celtic overlay.” More notably, it seems that the Celtic newcomers, as Estyn Evan suggested, also “reinforced an older and persistent regional distinction… Gaelic culture as a whole, like the Gaelic language, seems to have taken shape by being poured into an Irish mould, a mould having varied regional designs,” and he asked, “Did the Celts conquer Ireland, or rather did Ireland conquer the Celts?”

The Black Pig’s Dyke

One of the most remarkable pieces of evidence which lends weight to the probability that regional differences pertained in Ireland in the prehistoric period, is the continued existence today of parts of a great earthwork ‘wall’, which can be traced from Bundoran in County Donegal to South Armagh. This ‘wall’, known as the Black Pig’s Dyke, makes use of natural barriers and lakes for part of its length, and it must have been a formidable barrier to approaches from the south. The ‘wall’ is situated in a forward position within a drumlin belt, which consists of tens of thousands of “shapely streamlined mounds of boulder clay [which] provided a defence in depth for the kingdom of Ulster”.

Aiden Walsh noted: “Firstly, the Black Pig’s Dyke was not simply a two-line defence (double-bank and double-ditch); it was a three-line defence. The third line was composed of a timber palisade which paralleled the earthwork itself. Secondly, it is clear from [its] scale and nature that we are dealing with a defensive structure. The earthwork also faces south and is set on southern facing slopes to defend those on its northern side. Thirdly, it appears to have been deliberately and quite fully destroyed, presumably during wartime. The short excavation carried out in County Monaghan has told us that this stretch of the monument… was built in the last few centuries BC.

Perhaps we are dealing here with… a war extending across the land starting at the boundaries of a kingdom and culminating with the destruction of its capital.”

At the eastern end of the ‘wall’ is a massive enclosure, called ‘the Dorsey’. One evening in 1977, as members of an archaeological team went for an impromptu walk around the perimeter of the earthworks, they chanced upon a portion bulldozed that same day for land reclamation. To their surprise, they noticed the tops of rotted ancient posts just visible in the disturbed ground. As Chris Lynn wrote: “The discovery of this palisade underlines the strongly defensive character of the Dorsey. Its builders were not content to rely on the patch of wet bog for defence of the south-west corner but augmented the edge of the morass with the ditch and a stout palisade.”

A dendrochronological examination was to find that the timbers used to construct the palisade around the Dorsey had been felled a few years after 100 BC. Such massive physical constructions leave us with many unanswered questions. What of the people who were able to erect such impressive earthworks? As Victor Buckley pointed out: “The building of massive, travelling earthworks to monitor traffic northwards needed a cohesive society behind it, be it a monarchy, democracy or theocracy, which could call upon a large manpower-base and utilise vast natural resources.”

What of the war that has been suggested was the cause of its eventual destruction? Was this a war among the pre-Celtic peoples? Or was it between the original inhabitants and the first Celtic-speaking invaders? We will probably never know the answer, but one thing at least is certain — the history of Ireland from then on was that of a continual struggle for power between a multiplicity of factions and their ever-changing alliances.

Ptolemy’s Map

In the second century AD there came from upper Egypt one of the greatest of ancient scientists, known to us today as Ptolemy the Greek. He wrote a magnificent work comprising eight books, the Geographia Hyphegesis, in which he not only gives us an account of Ireland, but provides the earliest known “map” of the British Isles, on which is marked various tribal and geographical names. At the beginning of research into Ireland’s ‘Celtic’ roots, the map proved disconcerting to many scholars, because it seemed to contradict the then-assumed antiquity of the Gaelic occupation of Ireland.The renowned Irish linguist T.F. O’Rahilly could find no evidence of Gaelic names in Ptolemy’s account and pointed out that those names which could be traced were of Belgic British stock. To compensate it was suggested that Ptolemy was using sources going back to the fourth century BC. Yet the Roman occupation of the southern part of Britain had already been completed by 84 AD, and it is difficult to believe that the great scholars of the Roman Empire had to rely on sources 500 years old for information about an island their soldiers could see every day from the coast of Galloway and of which they had gained much intelligence through traders.

On Ptolemy’s map are recorded two capitals in Ireland, and two only. One is a place called Isamnion. Scholars now feel that this place is the ancient capital of Ulster, called Emain in the earliest Irish texts, and more generally known as Emain Macha. This ancient seat of the kings of Ulster — still surviving today as Navan Fort — contained a great ceremonial building, the timbers for which were felled at the same time as the massive defensive enclosure of the Dorsey, and presumably by the same population group.The second is Regia e Tera at the centre of County Galway, precisely where Turoe is today, the site of the famous Turoe Stone. An expansive inner ward of linear embankments encloses an acropolis and necropolis in the complex along the western slopes of Turoe and Knocknadala. According to Ptolemy this was “the most illustrious city in all Britannia (Pretania) and the most considerable in size, located in the Western part of Ireland”. It appears to have been the centre of Belgic power. At this time the indigenous Cruthin or Pretani still held Cruthintuatha Croghain, Rathcroghan in Roscommon.

When the written records become acceptable for historical purposes — in the sixth and seventh centuries — the fastest rising power in Ireland are those “Celts” we now call the ‘Gaels’. While this name has had to suffice as a all-embracing description of these particular Celts, we do not know just what mixture of peoples made up the original groups of immigrants, or in what way these newcomers soon had other tribes grafted onto them. Indeed, in the later writings of the early genealogists, ‘Gaelic’ tribes appear to gain a remarkable and posthumous increase. The name Gael itself is derived from the Brittonic ‘Guidel’, modern Welsh ‘Gwyddel’, meaning ‘raider’, and would suggest that the newcomers had no common name for themselves until they had come into contact with foreigners. The Romans called them Scotti (Scots) or marauders.

Just as we are not able to identify any particular group of Celtic invaders as being the first ‘Gaels’ to arrive on Irish shores, nor can we be certain about dates. According to Gaelic tradition itself Tuathal Techtmar (who was probably a Roman soldier) had led the ancestors of the Gaels to Ireland, where they overthrew some of the aithechthuatha (non-Gaelic, ‘unfree’ peoples) and established themselves in the area around Meath. Under the leadership of Mug Nuadat (Eogan), another party of Gaels were able to establish themselves in Munster, this conquest seemingly being effected with much less conflict than that of their ‘Midland’ associates.

According to the genealogical material contained within ‘Laud 610’ the date reckoned for Tuathal’s becoming king of Tara is 153 AD. Another source, Mael Mura, gave a reckoning of 135 AD. However, any dates given at this time must be treated with the greatest of caution, and all that can be said is that the Midland Gaels were obviously able to establish themselves and consolidate their power base, for by the time Ireland moves into the ‘historic’ period proper, we find these particular Gaels involved in a gigantic struggle for control of the north of the island — the ancient province of Ulster.

The first Gaelic leader who bridges that twilight zone between ‘purported’ and ‘actual’ history is Niall Noígiallach, known as ‘Niall of the Nine Hostages’, whose mother was British. From him the greatest dynasty to emerge from among the Gaels, the Uí Néill, claim direct descent. (The Uí Néill would much later become synonymous with the long family line of powerful Gaelicised chieftains, the O’Neills.) Although at the time of Niall’s reign — reckoned to be about the first quarter of the fifth century — Ireland was in the last phase of its unrecorded history, scholars find no reason to doubt his existence. While the middle of Ireland was still not secure to the Uí Néill — the ancient annals tell of battles between 475 and 516 before the Uí Néill conquered the plain of Mide — it appears that it was to the conquest of the North that Niall and his sons directed their first major efforts.

The Three Collas

Ancient tradition has it that a few generations before the reign of Niall, three brothers, the ‘Three Collas’, relatives of the then “king of Tara”, Muiredach Tírech, first initiated the attack on Ulster, though some scholars now feel the actual invasion was the work of Niall and his “sons”, and took place during his reign. The central battle was at Achadh lethderg, probably near Farney in County Monaghan in 331 AD.”The Collas asked: ‘what country dost thou of thy power the most readily assign us, that we make swordland of it? (for warriors better than the Collas there were none). Muiredach said: ‘attack Ulster; they are not kindly disposed to us.’ But yonder was a warrior force too great for the Collas; so they went to the men of Connacht, and became their protégés, and they received them. Subsequently Connacht came with them, seven battalions strong all told, and they were at the cairn of Achadh lethderg in Farney, in Ulster. From that cairn they deliver seven battles against Ulster, one daily to a week’s end: being six fought by Connacht and one by the Collas.

Every single day Ulster was routed; the Collas’ battle was on the last day; recreant failure in fighting was none there; the battle was maintained for a summer’s day and night, till blood reached shields; hard by the cairn is coll na nothar ‘Hazel of the Wounded.’ [In this last battle] Ulster gave way at break of the second day; the slaughter lasted as far as Glenree. A week then the others spent harrying Ulster, and they made swordland of the country”.At the time of Niall’s attempt at conquest we do not know what type of internal political structure existed in Ulster. Previous to the attack on the North, the existence of the massive earthwork defences — the ‘Great Wall’ — hinted strongly at a definite regional demarcation, even political boundary, and in the prehistoric period the territory of Ulster may not only have embraced the whole north of the island but stretched as far south as the Boyne valley. There was probably a system of tribal alliances, and within this the dominant political grouping were the Ulaid (from whom ‘Ulster’ was to get its name) — the Voluntii mentioned on Ptolemy’s map.

The Ulaid, according to Francis Byrne, “most probably represented a warrior caste of La Tène Celts from Britain, wielding an overlordship over indigenous tribes.” Among these ‘indigenous tribes’, who obviously still formed the majority of the population, the most important and the most populous were the Cruthin (Pytheas’ ‘Pretani’). These pre-Celtic peoples shared in the over-kingship of Ulster, particular those Cruthin later known as the Dál nAraidi (Dalaradians). The Cruthin more often than not bore the brunt of the wars against the Uí Néill, and at times claimed that it was they who were the fír-Ulaid, the ‘true Ulstermen’. In the far west of Ulster the Uí Neill conquest was said to have been the most complete, and most of the Ulster leaders there were driven east. Niall’s “sons”, Connall, Eogan (Owen), Enda and Cairpre, were said to have established their own kingdoms. But this was an eighth century propagandistic fiction. The territory of Connall, now Donegal, became known as Tir-Connall (the Land of Connall), and from Connall were descended the O’Donnells , but Conall was actually a Gaelicised Cruthin. The territory of Owen was Inishowen (the Island of Owen) but Owen was actually probably of the Ulaid. The Clan Owen later expanded into Tir Owen, which is now called Tyrone. From Owen descended the Northern O’Neills, the McLoughlins, O’Kanes, O’Hagans, O’Mullans, Devlins and other Gaelic-speaking settlers . Of all these “sons” Cairpre was probably the only genuine one, while Niall’s remaining sons stayed in control of the Midlands.

The capital of Ulster at Emain Macha seems to have either fallen to the “Uí Néill”, or been abandoned by the Ulstermen, around 450 AD. In the southern and central part of Ulster a number of vassal tribes, known to us by the collective name of the Airgialla (Oriel) either took the opportunity to declare their autonomy or managed to co-exist precariously between the “Uí Néill” and the retreating Ulstermen.

The boundary between Airgialla and the now-reduced territory of Ulster was made permanent by yet another massive earthwork wall, running along the vale of the Newry River (Glen Rige). It extended from Lisnagade one mile north-east of Scarva in County Down, to near Meigh, not far from Killeavy, and Slieve Gullion in Armagh. Parts of this earthwork, much later erroneously named “Dane’s Cast”, can still be seen to this day. In construction it consists of a wide fosse or trench with a rampart on either side. The numerous raths and duns on the eastern side, coupled with the vast quantity of ancient arms found in the vicinity, would seem to indicate that the area was densely populated by a strong military force. The chief fortifications were at Lisnagade, Fathom, Crown Mound, Tierney and Listullyard. Next to Lisnagade, Fathom must have been the most important place since it commands Moiry Pass. This defence system was to remain politically effective for the next two hundred years.

However, excepting the permanent nature of the “Dane’s Cast” fortifications, other parts of the new boundaries of Ulster were more fluid. As Francis Byrne commented: “It seems that the collapse of the Ulaid was not total nor regarded as irreversible. They may have occupied southern Louth well into the seventh century and their Cruthin associates were similarly tenacious in county Londonderry… The Ulaid certainly were to remain for many generations a much more powerful force than later historians of the Uí Néill high-kingship cared to remember.”

The Ulster Cycle

Among the great works of early Irish literature are a group of tales known as the Ulster Cycle, written in the Pretanian Abbot Comgall’s monastery of Bangor and traditionally felt to depict the North of Ireland in the first few centuries AD. While some scholars suggest that certain of the episodes enshrined within these tales have some bearing on actual historical events, this can only be speculation. But perhaps what we are looking at here is the hidden history of the Pretani . What we can say, however, is that the whole structure of society as depicted in the sagas, the weapons and characteristics of the warriors, and their methods of warfare, agree precisely with the descriptions by classical authors of life among the Britons and Gauls before the Roman invasions. So, while we cannot yet take them as ‘historical’ evidence, these stories nevertheless give us a glimpse, albeit romanticised, into Ireland’s Iron Age — its ‘Heroic’ Age — and are, moreover, a rich ingredient of this island’s cultural heritage.

According to the sagas, the great citadel at Emain Macha (Emania) contained within it three main buildings: that of the Red Branch, in which was kept the heads and arms of vanquished enemies; that of the Royal Branch, where the king lodged; and the Speckled House, in which were stored the swords, shields and spears of Ulster’s warriors. The latter building received its name from the gold and silver of the shields, and the glint from all the weapons, stored there in order that, when quarrels arose at any of the banquets, the warriors would not have the means at hand to slay one another! As Douglas Hyde wrote: “Conor’s palace at Emania contained, according to the Book of Leinster, one hundred and fifty rooms, each large enough for three couples to sleep in, constructed of red oak, and bordered with copper. Conor’s own chamber was decorated with bronze and silver, and ornamented with golden birds, in whose eyes were precious stones, and was large enough for thirty warriors to drink together in. Above the king’s head hung his silver wand with three golden apples, and when he shook it silence reigned throughout the palace, so that even the fall of a pin might be heard. A large vat, always full of good drink, stood ever on the palace floor.”

An eighth-century law tract, Críth Gablach, gives a somewhat unrealistic summary of a king’s duties: “There is moreover a weekly order proper for a king, i.e. Sunday for drinking ale, for he is no rightful prince who does not promise ale for every Sunday; Monday for legal business, for adjudicating between tuatha (tribes); Tuesday for chess; Wednesday for watching greyhounds racing; Thursday for marital intercourse; Friday for horse-racing; Saturday for judgements.” A place like Emain Macha would have been the venue for popular assemblies, which served not only as fairs and markets, but for the transaction of public business. These occasions were treated almost as holiday events, with horse-racing, feats of strength and various kinds of amusements on hand.

One of the legends as to how Emain Macha received its name relates to such a fair. Among the many spectators at a chariot race, in which the king’s victorious chariot and horses greatly impressed the crowd, was a man who imprudently boasted that his wife was a faster charioteer. The hapless man was brought straightway before the king, who, when he had heard the proud boast, immediately sent for the unsuspecting woman. However, when the messenger located her, she protested that she was heavy with child and was in no fit state to race. The messenger informed her that in that case things did not augur well for her husband. The woman knew she had no choice but to accompany him. The expectant crowd clamoured for her to race, and it was in vain that she pleaded her condition to them.

Finally she angrily told them that if they forced her to race, a long-lasting evil would fall upon the whole of Ulster. This still wasn’t enough to deter the crowd and she was forced to commence the race. Just as her chariot reached the end of the field, she tumbled from it, and, right before the assembled spectators, gave birth to twins. At the height of her labour she screamed out that in times of greatest danger a debilitating illness — the ‘pangs’ — would seize the warriors of Ulster and leave them lying as helplessly unable to fight as she was now lying in her labour pains. The woman’s name was Macha, and it is said that Emain Macha means the ‘Twins of Macha’.

The Ulster sagas are full of larger than life characters, both men and women. However, there is one who stands out above the others — the hero Cúchulainn, ‘Champion of Ulster’. Born in the plain just south of what is now the Cooley Peninsula in County Louth, his boyhood name was Sétanta, a non-Gaelic name which is cognate with a British tribe who lived in Lancashire, the Setantii, who are mentioned in Ptolemy’s map of the British Isles. One tradition, preserved by Dubhaltach, relates that he belonged to a non-Gaelic tribe called Tuath Tabhairn. In the sagas it also states that he was not of the Ulaid, the Celtic ruling minority in Ulster. The MS Harlean 5280 tells us categorically that “Cú Chulainn was exempt from [the sickness of the Ulstermen], ar nar bó don Ulltaib do, ‘for he was not of the Ulaid’.”

Further, his physical appearance was quite at variance with the physique of the Celts, for while they are usually described as tall, with long flowing fair hair, Cúchulainn is described as short in stature, with close-cropped dark hair, physical attributes more in keeping with the pre-Celtic inhabitants of Ireland. Finally, his inheritance, the plain of Muirthemne, was well-defined Pretani territory. Now, given such an assortment of circumstantial evidence, it could well be speculated that the legend of Cúchulainn emanated from among the majority Pretani population of Ulster. However, although such speculation is the daily and cherished practice of historians, for various reasons most have proven quite touchy in this case — perhaps it disturbs some long-established and jealously-guarded notions — so such speculation will not be indulged in here, and we will return to the hero’s own story.

Filled with an urge to visit Emain Macha and meet the elite fighting force billeted there known as the Warriors of the Red Branch, young Sétanta finally made his farewell to his parents and journeyed to the great citadel. Once there he made an immediate impression on King Conor and his warriors, but not before he had experienced the first of many uncontrollable fits of rage which would overcome him in moments of anger, change his physical appearance alarmingly, and endow him with almost superhuman fighting capability. Indeed, such a fit came upon him after his first border encounter with the enemies of Ulster, and the only way the concerned citizens of Emain Macha were able to prevent many of their own number being counted among his victims was to send the women of Ulster out to meet him, all quite naked. Our hero’s intense embarrassment caused him to falter, and this respite allowed the warriors to seize him and dissipate his rage by plunging him into vats of cold water.

His most famous deed while still a youth was one which would lead to a new name. Asked by Conor to accompany him on a visit to Culann the Smith, Sétanta accepted but requested that he be allowed to complete the game he was then engaged in. Conor agreed and told the youth to follow on behind. However, when the king and his retinue reached their host’s dwelling and the latter ordered the gates of the surrounding palisade to be secured, Conor omitted to mention that a final member of his party was following. Once the gates were secured Culann released his massive guard dog, so powerful that it took three chains to restrain it, with three men on each chain.

The reader can guess what transpired next. Sétanta, arriving outside the palisade, was savagely attacked by the dog, but after a fierce and bloody struggle managed to kill it. Conor and his host had by this time arrived on the scene, and while everyone was delighted that the youth had not only survived, but shown such remarkable fighting ability, Culann was devastated by the loss of such a magnificent guard dog. In an attempt to make amends, Sétanta offered to act as guard in the dog’s place, until such time as a pup of the same fierce breeding could be trained for the task. This suggestion was widely welcomed, and it was further pronounced that henceforth the young Sétanta would be known as ‘Cú Chulainn’, the ‘Hound of Culann’.

However, Cúchulainn’s greatest glory was to be accorded him after he had repelled a massive invasion force which threatened the very survival of Ulster itself.

Setanta or Cúchulainn, Champion of Ulster

Statue of “The Dying Cúchulainn ” by Oliver Sheppard (1911), now at the GPO, Dublin.

The image of Cúchulainn is invoked by both Irish nationalists and Ulster Loyalists. Largely due to the efforts of the deluded Irish patriot Patrick Pearse, Irish nationalists see him as the greatest “Celtic” Irish hero, and thus he is important to their whole culture. A bronze sculpture of the dead Cúchulainn by Oliver Sheppard stands in the Dublin General Post Office (GPO) in commemoration of the Easter Rising of 1916. By contrast, unionists and loyalists see him as an Ulsterman defending the province from enemies to the south: in Belfast, for example, he is depicted in a UDA mural on Highfield Drive and another in Rathcoole describes him as “The beginning of the Red Hand Commando” He was formerly depicted in another UDA mural on the Newtownards Road, as the “defender of Ulster from Irish attacks”. These murals are ironically based on the Sheppard sculpture. He is also depicted in murals in nationalist parts of the city and many nationalist areas of Northern Ireland. The statue’s image was also used on the Irish Republic’s ten shilling coin produced for 1966. The 1916 Medal, the 1916-1966 Survivors Medal and the Military Star for the Irish Defence Forces all have the image of Cúchulainn on their Obverse.

The ancient tale known as the Táin Bó Cuailgne, the ‘Cattle-Raid of Cooley’, is the masterpiece of Irish saga literature. Indeed, it is the oldest vernacular story in Western European literature, and therefore holds an eminent place not only within the development of Irish literature, but within that of European literature as well. Thomas Kinsella has pointed out: “The language of the earliest form of the story is dated to the eighth century, but some of the verse chapters may be two centuries older [and] must have had a long oral existence before [receiving] a literary shape.”

The story concerns an assault upon Ulster by the massed armies of the ‘men of Ireland’, led by Maeve, the Belgic Queen of Connacht. The opening scene is set in Rathcroghan (Cruachan), the ancient ceremonial site of the western Pretani or Cruthin, euhemerised into Maeve’s capital. In reality Maeve’s home stood beside the great Turoe Stone in County Galway. As Queen of ancient Ól nÉchmacht, her royal palace was at Ruath Cruacha, Athenry. She was eventually to be assassinated in Loughrea Lake and buried in Fert Medb at Athenry’s Releg na Rí lamh le Cruacha.

The bloody and bitter fighting in the Táin Bó Cuailgne has all the hallmarks of a full-scale invasion, and the appellation of ‘cattle raid’ hardly does justice to the carnage wrecked upon Ulster. However, as Charles Doherty pointed out: “In this society cattle were the basis of the economy. There was no coinage before the Norse began to mint in the late tenth century, and cattle were used as the main units of value. The constant cattle-raiding which took place was the parry and thrust of politics.” Francis Byrne also commented: “As tribute was usually reckoned in cattle, the ‘wars’ tended to be primarily cattle-raids.”

No sooner were Maeve’s armies making their advance into the North than the fighting men of Ulster were afflicted with their ‘pangs’ and could offer no resistance. Cúchulainn, who, as we have already seen, was unaffected by this debility, had to defend his homeland single-handedly. While the story then concentrates on the gigantic and bloody one-sided battle that now raged (one-sided, that is, from the point of view of the invaders, for their ranks were steadily decimated by Ulster’s hero), the saga also brings in a very tragic episode — the combat between Cúchulainn and his southern foster-brother, Ferdia. Unlike the approach taken with the other battle sequences, where blood and heads fly as a matter of course and where humanitarian considerations seem remote, the story of this combat between the two men is described with great emotion, pathos, even tenderness. While this pathos is undoubtedly directed at the tragedy of two foster-brothers thus locked in mortal combat, nevertheless the episode is a remarkably moving depiction of the absurdity and futility of man’s preoccupation with violence and killing.

Finally King Conor managed to raise himself from his ‘pangs’ and summoned his warriors with a rousing battle oration: “As the sky is above us, the earth beneath us and the sea all around us, I swear that unless the sky with all its stars should fall upon the earth, or the ground burst open in an earthquake, or the sea sweep over the land, we shall never retreat one inch, but shall gain victory in battle and return every woman to her family and every cow to its byre.”

Soon, as Queen Maeve scanned the plain before her, she saw a great grey mist which filled the void between heaven and earth, with what seemed like sifted snow falling down, above which flew a multitude of birds, and all this accompanied by a great clamour and uproar. One of Maeve’s warriors turned to her. “The grey mist we see is the fierce breathing of the horses and heroes, the sifted snow is the foam and froth being cast from the horses’ bits, and the birds are the clods of earth flung up by the horses’ dashing hooves.”

“It matters little,” retorted Maeve, “we have good warriors with which to oppose them.”

“I wouldn’t count on that,” replied the warrior, “for I assure you you won’t find in all Ireland or Alba a host which can oppose the Ulstermen once their fits of wrath come upon them.”

The warrior’s prediction was quite accurate, for Maeve’s armies were completely routed and fled in disarray, Maeve herself only escaping death through Cúchulainn’s personal intervention.

Maeve never forgave Cúchulainn the humiliation she and her army had suffered as a result of their inglorious incursion into Ulster. Even his sparing of her life was immaterial to her intense desire for revenge. Conor, suspecting that Maeve was plotting the Champion’s downfall, ordered him to be sent into seclusion, but Maeve, calling upon the dark arts of magic, had his mind so bewitched he hallucinated that his enemies were once again invading and despoiling his homeland. Cúchulainn’s wife, Emer, realising that things were greatly amiss with her beloved, redoubled her efforts to restrain him from dashing out of Emain Macha to do battle. Despite being reassured that his visions were unreal phantoms, they persisted, and finally Cúchulainn managed to slip away from the security of his friends, having convinced his loyal charioteer, Laeg, to accompany him.

Cúchulainn then encountered a series of ill omens, and realised that events were rapidly taking him to his final destiny. His enemies were drawn up, in full battle array, their chosen battleground Cúchulainn’s ancestral territory — Mag Muirthemne. Once more, Cúchulainn proved why he inspired so much terror in the hearts of his enemies.He played equally with spear, shield, and sword, he performed all the feats of a warrior. As many as there are of grains of sand in the sea, of stars in the heaven, of dewdrops in May, of snowflakes in winter, of hailstones in a storm, or leaves in a forest, of ears of corn in the plains of Bregia, of sods beneath the feet of the steeds of Erin on a summer’s day, so many halves of heads, and halves of shields, and halves of hands and halves of feet, so many red bones were scattered by him throughout the plain of Muirthemne, it became grey with the brains of his enemies, so fierce and furious was Cúchulainn’s onslaught.

However, with his enemies now being aided by the sinister forces of magic, the outcome was inevitable. Three of Cúchulainn’s bitterest enemies confronted him with a spear which they were told had magical powers and would that day lay low a king. The first throw, however, instead of piercing Cúchulainn, killed his faithful companion, Laeg — the ‘king’ of charioteers. Furious, his assailants threw again, but this time it was the Champion’s noble steed, the Grey of Macha — the ‘king’ of steeds — which received a mortal wound and galloped off. The third throw finally struck Cúchulainn, causing a terrible injury to his stomach.

The fatally-wounded Champion struggled over to a tall stone and tied himself to it, so that he could die standing. As his enemies edged closer, still in awe of this great warrior, Cúchulainn’s dying but ever-faithful steed returned once more to his side, scattering the advancing foes with terrible charges into their ranks. It was all to no avail, and Cúchulainn’s enemies sensed that victory was finally to be theirs. Yet, even after one of them smote off the Champion’s head, Cúchulainn’s sword, falling now from his lifeless arm, severed the hand of his assailant.

As his enemies rejoiced and celebrated their great victory around the dead hero, his lifelong friend Conall Cearnach came upon the scene, and in a terrible fit of anger exacted a fierce revenge, before finally carrying the body of his companion back to Emain Macha. Emer, on seeing her dead husband, was smitten with intense grief. She washed clean the head and she joined it on to its body, and she pressed it to her heart and her bosom, and fell to lamenting and heavily sorrowing over it, and she placed around the head a lovely satin cloth.

‘Ochone!’ said she, ‘good was the beauty of this head, although it is low this day, and it is many of the kings and princes of the world would be keening it if they thought it was like this. Love of my soul, O friend, O gentle sweetheart, and O thou one choice of the men of the earth, many is the woman envied me thee until now, and I shall not live after thee’, and her soul departed out of her, and she herself and Cúchulainn were laid in the one grave by Conall, and he raised their stone over their tomb, and he wrote their names in Ogam, and their funeral games were performed by him and the Ulstermen.

Deirdre and the Sons of Usnach

Our brief résumé of the richness of the Ulster Tales would be incomplete without mention of one of the oldest stories of romance, adventure and treachery in Western European literature — the story of the ‘Fate of the Children of Usnach’, more popularly known as ‘Déirdre of the Sorrows’ after the play by J. M. Synge. This beautiful story is as much part of the popular tales of the West Highlands of Scotland as it is of Ireland. From Naisi, son of Usnach, for example, came the name of Loch Ness. There are six or seven versions of the Scottish story, the oldest being in the manuscript dated 1208, in the Advocates’ library. It was written in Glenmassan, in Cowal. The longest version and the Book of Deer are the oldest written specimens that we possess of written Gaelic in Scotland.

It so happened that King Conor and some of his warriors were feasting at the home of his chief storyteller, when their host’s wife gave birth to a girl. This was seen as cause for even more celebration, and the king’s seer, Cathbad, was called upon to prophesy the child’s future. The child, he said, would grow up to have exceptional physical qualities: curling golden hair, green eyes of great beauty, cheeks flushed like the foxglove, teeth white as pearls and a tall, perfectly shaped body.

However, the pleasure of the assembled gathering was immediately dissipated when the seer continued with his prophecy. This child, because of her very great beauty, and the intense jealously it would cause, would bring a terrible evil upon the whole of Ulster, which would result in untold suffering and countless graves.The warriors of Ulster were horrified and clamoured that the only way to avert such a tragedy would be to have the child slain. Conor, perhaps with feeling for his host and his distraught wife, but no doubt also with his shrewd eye on an opportunity not to be missed, announced that the child would be allowed to live, but to prevent the predicted jealousy, and thereby avert the threatened doom, he himself would take the girl to be his wife when she came of age.

So it was that Déirdre was reared by her nurse in a secluded part of the king’s palace, where no man, other than her tutor or the king, was permitted to set foot. As she grew up, her physical beauty proved to be everything that Cathbad had prophesied.

However, one day her tutor killed a young calf, and as it lay on the snow a raven came to drink the blood. Déirdre turned to her nurse and said, “The only man I could love would be one who should have those three colours, hair black as the raven, cheeks red as the blood, body white as the snow.” Her nurse revealed that there was such a young man living in Emain Macha — Naisi, one of the three sons of Usnach. So great was Déirdre’s desire to see this youth that she convinced her nurse to arrange a seemingly innocent encounter while he was out walking.

The young pair fell instantly in love, although Naisi was too mindful at first of incurring Conor’s wrath to want to get too involved. But the dictates of love, and Déirdre’s own pleadings, soon got the better of his fears, and one night the couple slipped away in the darkness, accompanied by Naisi’s two brothers. Realising that Conor would hunt the length and breadth of Ulster for the fugitives, the youthful party finally departed for Alba (Scotland).

However, Déirdre’s beauty attracted male attention once again, and the couple had to keep on the move, continually harassed by the men of Alba, until they managed to set up home in the beautiful Glen Etive.

As time passed many were those who counselled Conor to forgive the exiles their insult to him, saying it would be a tragedy for three sons of Ulster to die at the hand of enemies abroad. The aging king finally agreed to send messengers to bid them return home. These emissaries convinced Naisi and his brothers that all was forgiven and it was safe to return, though Déirdre remained disbelieving.

The group finally journeyed to Ulster, to be met by their good friend Fergus, one of the most respected warriors of the Red Branch. It was his promise to watch over them — and his threat to kill anyone who harmed them — that had finally helped persuade them to return. But Conor, by trickery, managed to divert Fergus from his task, and the party were entrusted to the protection of Fergus’ two sons. As the omens of evil gradually grew thicker, Déirdre’s premonition of treachery intensified.

“O Naisi, view the cloud That I see here on the sky, I see over Emania green A chilling cloud of blood-tinged red”.

Upon their arrival at Emain Macha, instead of being admitted to the king’s own lodgings, they were accommodated in the House of the Red Branch, on the pretence that it was better stocked with food and drink for strangers. The party realised now that all was far from well.

Late that night Conor, still fired with his jealously, asked Déirdre’s old nurse to find out if her former charge still retained her great beauty. The nurse, after warning the young couple that Conor was a great threat to their safety, returned to the king and tried to convince him that time had indeed taken its toll of Déirdre’s looks, with much of her beauty now lost. This seemed to satisfy Conor for a while, but, being suspicious of the report, he sent another retainer to ascertain the truth. This spy finally found a chink in the barred windows and doors of the House of the Red Branch and observed the two lovers within. They in turn spotted him and angrily flung a chess piece which put out his eye.

The injured man hurried back to Conor, telling the king that it was worth losing an eye to have beheld a woman so lovely.

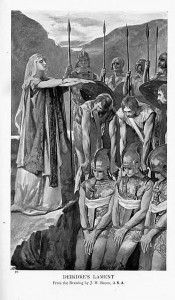

Conor straightway gathered together a force of men and began an assault on the House of the Red Branch. By the dawn, although one of Fergus’ sons lay slain in his attempt to defend his charges, the three sons of Usnach were captured and beheaded. Déirdre’s lament over her lover’s dead body is one of the masterpieces of early Irish tragic verse, and was much rewritten by Irish scribes.

“Naisi is laid in his tomb. sad was the protection that he got; the nation by which he was reared poured out the cup of poison by which he died. His ruddy cheeks, more beautiful than meadows, red lips, eyebrows of the colour of the chafer, his teeth shining like pearls like noble colour of snow. Break not to-day my heart (O Conor!), soon I shall reach my early grave, stronger than the sea is my grief dost thou not know it, O Conor?”

When Fergus heard of the treachery and Conor’s subsequent abduction of Déirdre, he and many other outraged Red Branch warriors fell upon Emain Macha and killed three hundred of those who remained loyal to Conor, as well as many women and members of Conor’s own family. Then they burned Emain Macha and departed into exile, a full three thousand of them. Taking up service with their former adversary, Queen Maeve of Connacht, they made continual raids upon their former homeland, killing and despoiling in revenge for the murder of the sons of Usnach.

As for Déirdre, she never smiled again, and Conor, finally tiring of this, in annoyance asked her what she hated most. To which question she named the king himself and one of his closest retainers. “Well then,” said the vindictive Conor, “I shall send you to his couch for a year.” As Conor rode out the next day, with Déirdre behind him in the chariot, she suddenly flung herself onto the ground, and dashing her head against a rock was instantly killed.

While these sagas are believed to describe an Ulster of the first few centuries AD, and probably had a long oral existence, they only took literary form in the eighth and ninth centuries. However, the development of Irish writing which made this flowering of culture possible was to be proceeded by the introduction into Ireland of a new and powerful force which was to have a fundamental impact on the Irish peoples and their history.

The ancient Annals of Ulster record two significant events, occurring one year apart:

In the year 431 from the Incarnation of the Lord, Palladius, ordained by Celestinus, bishop of the city of Rome, is sent, in the consulship of Etius and Valerius, into Ireland, first bishop to the Scots (Irish), that they might believe in Christ.”

“AD 432. Patrick arrived at Ireland, in the 9th year of the reign of Theodosius the younger, in the first year of the episcopate of Xistus, the 42nd bishop of the Church of Rome.”

While some historians continue to accept c 460 for Patrick’s death, most scholars of early Irish history tend to prefer a later date, c. 493. Supporting the later date, the annals record that in 553 “the relics of Patrick were placed sixty years after his death in a shrine by Colum Cille” (emphasis added).

Ireland’s period of ‘ancient’ history was now at an end — an new era was about to begin.